Veronica Johnson, University of Maryland Department of Entomology

Aphids are small, early season pests that can occasionally reach damaging levels in small grain fields in Maryland. Strategies to control these insects should begin with correct pest identification and field scouting to determine infestation levels within a particular field.

Pest Identification:

Aphids are soft bodied, pear-shaped insects with piercing-sucking mouthparts and a pair of “tailpipe-like” projections, or cornicles, emerging from their lower abdomen. Adults can be winged or wingless, and the vast majority of aphids are female. A number of aphid species have been documented as either direct or indirect pests of wheat in Maryland. These include the bird cherry oat aphid, english grain aphid, corn leaf aphid, and the greenbug aphid.

Bird Cherry Oat Aphid:

The bird cherry oat aphid is a large aphid species that vares in color based on growth stage and the temperature of the surrounding environment. Most commonly, it is an olive-green color with reddish-orange coloring along the base of the abdomen (Fig. 1). This species is one of the first to colonize small grain plants, and adults often persist late into the winter.

Greenbug:

Greenbugs are pale green aphids with a dark line running along the back center of their bodies (Fig. 2). Greenbugs often concentrate in large colonies and prefer to feed on the underside of the lower leaves. Feeding by large enough colonies can eventually cause leaves to turn yellow, then reddish-brown and eventually die (Fig 6-A). Larger plants are able to tolerate larger populations of greenbugs.

English Grain Aphid:

English grain aphids are one of the largest aphid pests of wheat and can be found in a variety of colors including yellow, green, orange or reddish-brown. They have long black legs and cornicles, and the antennae stretch nearly half the length of the body (Fig. 3). English grain aphids can be found in wheat through maturity and can directly damage kernels if they begin feeding within the heads. These aphids are relatively active and differ from other aphid species in that they generally do not form tight colonies.

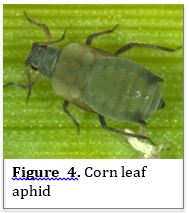

Corn Leaf Aphid:

The corn leaf aphid is a blue-green or gray aphid with dark green or black cornicles (Fig. 4). Physical damage caused to small grains by this pest is generally minor, however the insect, along with most other aphid species, is capable of transmitted Barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV). Thus, populations should be monitored in order to avoid disease transmission.

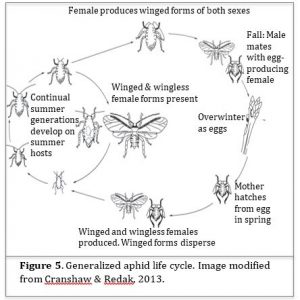

Aphid Life Cycle:

Aphid development is notably different than many organisms due to the almost complete absence of males, which are only produced during one generation in late summer (Fig. 5). After mating, the females in this generation lay eggs, the overwintering stage of most aphid species. These overwintering eggs will begin to hatch when springtime temperatures exceed 45°F. The emerging aphids are all female and, in the absence of males, will later give birth to live offspring that are genetically identical to the mother.

At the time of their birth, these offspring are already pregnant and have begun to internally mature their own young. This rapid maturation and reproduction means that aphid populations can build very quickly, resulting in pest outbreaks that arise unexpectedly. This type of parthenogenic reproduction occurs throughout the summer, with an average of nine generations occurring before temperature and light changes in the environment signal the approaching arrival of winter, causing aphids to produce a single generation of both males and females.

Pest Damage & Disease Transmission

In most cases, aphid populations do no t become large enough to cause physical feeding damage that results in yield losses or significant plant death. An exception to this is greenbug aphids, who secrete a toxin into the leaves when feeding. Populations of greenbugs can occasionally build to large enough numbers to cause yellowing of the leaves, which will eventually progress to a reddish-brown color and kill the plant (Fig 6-A.). Additionally, large populations of bird cherry oat aphids feeding beyond the boot stage can cause the flag leaf to twist into a corkscrew shape that can trap the awns, resulting in “fish-hooked” heads (Fig 6-B). Finally, because the English grain aphid remains in wheat through physiological maturity, large populations feeing on the heads can potentially damage kernels, causing them to shrivel. Scouting for English grain aphids is particularly important because heavy head infestations often occur in fields containing lower canopy infestations earlier in the season. Heavy head infestations of English grain aphids can reduce yields by up to 13%. The most damaging aspect of aphid feeding, however, is their potential to transmit Barley yellow dwarf virus.

t become large enough to cause physical feeding damage that results in yield losses or significant plant death. An exception to this is greenbug aphids, who secrete a toxin into the leaves when feeding. Populations of greenbugs can occasionally build to large enough numbers to cause yellowing of the leaves, which will eventually progress to a reddish-brown color and kill the plant (Fig 6-A.). Additionally, large populations of bird cherry oat aphids feeding beyond the boot stage can cause the flag leaf to twist into a corkscrew shape that can trap the awns, resulting in “fish-hooked” heads (Fig 6-B). Finally, because the English grain aphid remains in wheat through physiological maturity, large populations feeing on the heads can potentially damage kernels, causing them to shrivel. Scouting for English grain aphids is particularly important because heavy head infestations often occur in fields containing lower canopy infestations earlier in the season. Heavy head infestations of English grain aphids can reduce yields by up to 13%. The most damaging aspect of aphid feeding, however, is their potential to transmit Barley yellow dwarf virus.

Barley yellow dwarf virus causes stunting and yellowing of the plant leaves, and has the potential to significantly reduce grain yields. Early spring infections often resemble phosphorus deficiency and can be identified by the presence of purplish flag leaves (Fig 6-C). Differences in infection from one field to the next can be due to differences in aphid mobility and feeding habits, differences in weather conditions, the source and strain of the virus, as well as the age and susceptibility of plants when infected. Yield reductions due to BYDV are greatest when the infection occurs in the fall, or early stages of the plant.

Thresholds & Management Options

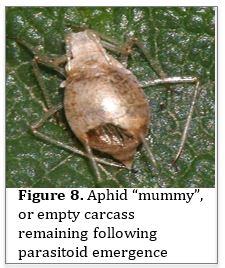

Natural Enemies: Aphids are usually kept below economic injury levels via biological control by various natural enemies – primarily ladybird beetles, lacewings, hoverflies, and parasitic wasps (Fig 7). Begin looking for ladybird larvae and “mummies”, or parasitized aphid bodies (Fig 8), once springtime temperatures begin to increase. Most natural enemies become active around 50°F. Once parasitism levels reach between 10 and 15%, aphid populations usually begin to decline. Additionally, it is important to avoid nonessential pesticide applications once these natural enemies are observed in the field, as any sprays targeting aphids will also reduce natural enemy populations, often leading to secondary outbreaks and increased aphid numbers.

Cultural Controls:

In addition to biological control of aphids, a number of cultural controls can also be employed to help reduce damage associated with aphid pests. Greenbug-resistant wheat varieties are available, so consulting with seed suppliers about available cultivars can be helpful if fields are consistently prone to greenbug infestations. Additionally, no-till wheat has been shown to have fewer aphid outbreaks due to the large amount of residue remaining on the soil surface.

Scouting & Insecticide Applications:

Aphid numbers can vary greatly between fields, so it is important to inspect every field before applying any insecticides. Scouting for aphids in small grain fields should begin around mid-March, or once daytime temperatures begin to reach 45°F. At this point, scouts should examine one linear row-foot at 10 sites within the field. The economic threshold for aphids in wheat in pre-heading stages varies based on the aphid species present. Treatment for greenbug aphids is justified if 25 to 50 or more aphids are present per linear row foot during the early seedling stage. Later stages of wheat rarely require aphid control. Bird cherry oat aphids are capable of transmitting BYDV, and therefore have a lower economic threshold. Treatment is justified when 12 to 25 aphids per linear row foot are found from fall seedling emergence through heading of plants the following spring. The Englis h grain aphid, on the other hand, is not capable of transmitting the disease, and treatment for these pests is rarely necessary. Only when populations of 100 or more aphids per tiller are present is treatment required. Finally, corn leaf aphids are heavily impacted by predator and parasitoid populations, and therefore rarely reach high enough levels to require treatment. As such, no official economic thresholds have been determined for this pest. Once the grain head has begun to develop, 10 heads in 10 sites should be examined weekly, and treatment should be considered when 25+ aphids per head are found. In addition to noting the presencce and abundance of natural enemies, the growth stage of the plant as well as additional stressors, such as drought, should be noted. Aphid outbreaks are often favored when an abrupt shift to colder temperatures occurs after a warm spell in spring.

h grain aphid, on the other hand, is not capable of transmitting the disease, and treatment for these pests is rarely necessary. Only when populations of 100 or more aphids per tiller are present is treatment required. Finally, corn leaf aphids are heavily impacted by predator and parasitoid populations, and therefore rarely reach high enough levels to require treatment. As such, no official economic thresholds have been determined for this pest. Once the grain head has begun to develop, 10 heads in 10 sites should be examined weekly, and treatment should be considered when 25+ aphids per head are found. In addition to noting the presencce and abundance of natural enemies, the growth stage of the plant as well as additional stressors, such as drought, should be noted. Aphid outbreaks are often favored when an abrupt shift to colder temperatures occurs after a warm spell in spring.

Both seed treatments and foliar insecticides are available for aphid control in small grains. Seed treatments offer the greatest value for early planted winter wheat, protecting newly emerged seedlings for two to three weeks. Imidicloprid, thiamethoxam, and clothianidin are the primary active ingredients used for seed treatments in small grains. Aphid populations exceeding economic thresholds later in the spring, however, will not be affected by seed treated insecticides and may require foliar sprays to reduce population levels depending on the number of natural enemies present. For more information on chemical control of aphids, contact your local extension office.