Alan Leslie1, Agriculture Agent; Kelly Hamby2, Extension Specialist; and Galen Dively, Professor Emeritus2

1University of Maryland Extension, Charles County

2University of Maryland, Department of Entomology

This time of year, anyone growing small grains will be planning to apply fungicides to manage Fusarium head blight, and many will consider tank-mixing an insecticide to control any insect pest problems at the same time. These tank mixes are an appealing option to reduce the time, fuel, and damage to the crop from having to make a second pass over the field later on in the season. In addition, with many synthetic pyrethroids now available as cheaper generic versions, the costs associated with adding an insecticide to the tank may seem like cheap insurance against possible pest outbreaks. However, to ensure that this added investment gives you a return with increased yields, you should still follow an integrated pest management approach and base the decision to add an insecticide on scouting and documentation of an existing pest problem. Below, we outline several possible insect pests that could be controlled with an insecticide applied with fungicides over small grains, and summarize situations where that application may be warranted, and when it may not.

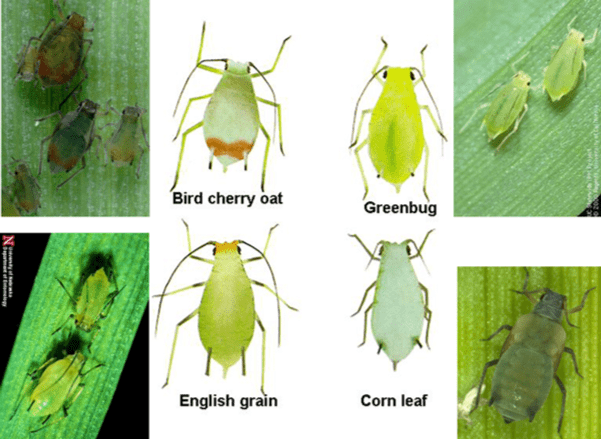

Aphids. Aphid populations need to be controlled in the fall to reduce Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus incidence in small grains. Spring insecticide applications will not reduce incidence of the disease. Only a few aphid species tend to feed on grain heads, and can reduce yield from head emergence through milk stage (Fig. 1). After the soft dough stage, no economic losses occur. Aphid populations are generally kept in check by insect predators and parasitoids, and thresholds for chemical control of aphids in the spring require at least 25 aphids per grain head (with 90% of heads infested) or 50 per head (50% heads infested) and low numbers of natural enemies. Applying a broad spectrum insecticide when aphid pressure is not above threshold tends to kill off beneficial predatory and parasitic species, which can allow aphid populations to flare up, as they are no longer being suppressed by their natural enemies.

True armyworm and grass sawfly. Both true armyworm (Fig. 2) and grass sawfly (Fig. 3) are sporadic pests of small grains and their pest pressure and feeding damage can vary widely from year to year. Automatically applying an insecticide to target these pests is not likely to be a cost-effective strategy since they are not pests that reliably cause economic injury. When these pests are present in high numbers, they are capable of causing significant yield loss through their behavior of clipping grain heads. Scouting should be done to check for the presence of these two pests and insecticide treatment is only needed if they exceed threshold values of one larva per linear foot for armyworm and 0.4 larvae per linear foot for grass sawflies.

Hessian fly. Cultural methods are the best way to control Hessian fly in small grain, such as planting after the fly-free date, selecting resistant varieties, and using crop rotation to disrupt their population growth. Spring feeding by the fly larvae can cause stems to break, reducing yields. There are no effective rescue treatments for Hessian fly; insecticides targeting fly larvae are ineffective since they are well protected from sprays by feeding inside of the leaf sheath (Fig. 4). If this year’s crop is damaged, it is imperative that fly-resistant varieties are planted after the fly-free date next year.

Cereal leaf beetle. This species is widespread in Maryland and is typically present in small grains, though it only occasionally reaches levels that injure crops. Cereal leaf beetle larvae chew the upper surfaces of leaves, leaving them skeletonized (Fig. 5). Larvae can cause yield loss if the flag leaf is severely skeletonized before grain-fill is completed. Insecticides with good residual activity tank mixed and applied with fungicides can potentially control populations of cereal leaf beetles, protect the flag leaf, and improve the yield of the crop if beetle pressure is high. However, predicting whether populations will reach damaging levels is not straightforward, and scouting should be used to guide spray decisions. If a field has 25 or more larvae plus eggs per 100 tillers, and there are more larvae than eggs, then chemical control is needed. In Maryland, a parasitoid wasp species (Anaphes flavipes) may parasitize 70-98% of cereal leaf beetle eggs, so if a field is dominated by eggs with few larvae, insecticide may not be needed. Additionally, feeding by cereal leaf beetle will not cause economic damage after the hard dough stage. So far, we have received no reports of economic levels of cereal leaf beetle in the region.

In conclusion, tank mixing an insecticide with your fungicide application can pay off if you have economically damaging levels of an insect pest, but applying any insecticide without a pest problem will not pay off. If populations are present, seem to be increasing, and you will not be harvesting soon, you could gamble. The risks of that gamble include losing money on an unnecessary input cost, secondary pest outbreaks if natural enemy populations are wiped out, or the target pest outbreaks anyway because the application was poorly timed. Scouting fields regularly to document pest pressure and using IPM thresholds as a guide for using chemical controls is the best way to hedge your bets when deciding whether to add an insecticide to the tank this spring.

For more information on tank-mixing insecticides with small grain fungicide applications, check out current research updates from Dr. Dominic Reisig at North Carolina State University: https://smallgrains.ces.ncsu.edu/2019/03/aphids-in-wheat/

https://entomology.ces.ncsu.edu/2015/04/should-you-spray-cereal-leaf-beetle/

And Dr. David Owens at the University of Delaware:

https://www.udel.edu/academics/colleges/canr/cooperative-extension/fact-sheets/cereal-leaf-beetle/