Andrew Kness, Agriculture Agent

University of Maryland Extension, Harford County

Given current commodity prices, growers may be considering increased corn acreage. Continuous corn presents additional risks in terms of disease that you need to proactively manage. Here are some points to consider so that you can try to stack the deck in your favor in case conditions become favorable for pathogens that threaten corn yields.

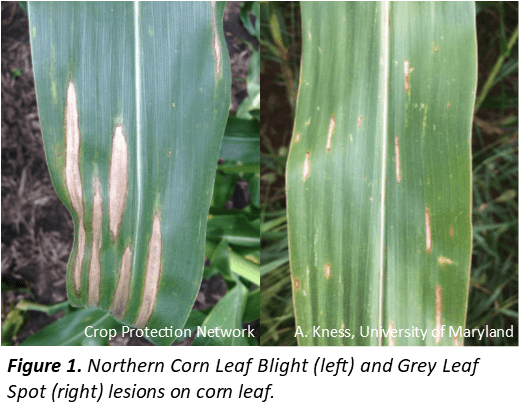

Here in our region of the world, we typically have plenty of humidity and moisture that favor disease development in our crops. Furthermore, our most common and potentially most severe yield-limiting diseases, such as grey leaf spot (GLS), northern corn leaf blight (NCLB) (Figure 1), as well as stalk rots, are residue-borne and overwinter in corn stover. The following are points to consider for disease management in a corn-on-corn system:

- Variety Selection: You can do yourself a big favor right off the bat by selecting hybrids that have good stalk integrity ratings and resistance to NCLB and GLS. Genetic resistance is one of the most cost-effective ways to manage disease. If you’re planting corn into corn, especially in a reduced or no-till situation, place hybrids with good NCLB and GLS resistance in these fields and save your more susceptible hybrids for fields that have lower disease potential (for example, after soybeans).

- Residue Management: Several pathogens of corn survive and overwinter in corn residue; therefore, residue is the primary source of infection. Not surprisingly, more corn residue present on the soil surface means that the following corn crop is at a higher risk of developing these diseases. While no-till and reduced-till systems afford us many benefits in crop production, harboring pathogen inoculum is one of the drawbacks. Chopping and sizing corn residue in the fall into smaller pieces can help accelerate its decomposition and may reduce inoculum (spores) slightly at best. In order to reduce inoculum significantly, more aggressive tillage is necessary to bury the residue. If you’re trying to build soil health and utilize no-till or reduced tillage, this may not be an option and you will need to make sure you are doing a good job in all other areas of disease management.

- Planting: Getting planting equipment and planting conditions correct is important, especially for seedling and root-rotting diseases of corn. Ensure you’re achieving proper planting depth, as the longer the seed sits in the ground, the more prone it will be to rot and dampen off. Soil temperature is important for getting the seedings off to a quick start, so it is advisable to wait until soil temperatures are at least 50 degrees and rising to plant; this is especially important for corn-on-corn. Fields with reduced tillage, cover crops, and substantial cover will warm up slower than tilled fields or fields with less cover (i.e. last year’s soybean fields). You may consider planting corn in last year’s bean fields first, then your corn after corn fields to ensure soils are warm enough for rapid and uniform emergence. Additionally, do not push plant populations too high, as excessive plant populations can cause dense canopy humidity which favors disease development and can stress plants if nutrients and/or water become limiting, which will predispose plants to pathogen infection.

- Seed Treatments: Nearly all commercial corn hybrids come pre-treated with seed treatments, which typically contain a fungicide. These fungicides will provide some protection from many seed and root-rotting pathogens for about two weeks.

- Weather and Scouting: Weather plays a crucial role in disease development. Cool, saturated soils in the spring favor the development of our seed and root-rotting diseases. Moisture, humidity and excessive leaf wetness, coupled with moderate to warm temperatures favor the development of NCLB and GLS (64-81°F for NCLB, 70-90°F favor GLS). Both of these pathogens will infect susceptible and moderately susceptible hybrids throughout the growing season as long as the weather is conducive for their development; however, you want to keep an eye on them as to where their lesions are present on the plant. Infections on the lower leaves have no impact on yield; however, if they infect the ear leaf and above, there is a potential for significant yield reduction. Scout your fields at least weekly as plants approach tasseling to make sure NCLB and GLS are not encroaching on the ear leaf. Look for the presence of lesions as shown in Figure 1. If infections are approaching the ear leaf, then you may want to consider a fungicide application.

- Fungicides: Fungicides can be an important management tool for foliar fungal pathogens, in particular NCLB and GLS. If temperatures remain between 65-90°F in conjunction with high humidity and excessive leaf wetness as the plants approach reproductive stages, then a fungicide application around tasseling (VT) may be beneficial to protect yield. Determining whether a fungicide application will be economically beneficial is the difficult part, and knowing your cost of application can help you make a decision so that you know how many bushels you need in return to pay for the fungicide. There have been hundreds of University fungicide trials conducted on corn over the years, and less than 50% of the time are fungicide applications economical. It is important to realize that there are conditions where a fungicide application is more likely to pay; they are: 1.) Applied at VT to a susceptible or moderately susceptible corn hybrid, 2.) Corn-on-corn, especially in no-till fields, 3.) environmental conditions are favorable for disease development (warm, humid, and leaf wetness) at the time around VT.There is also interest in applying fungicides for perceived stalk strength benefits. In general, fungicides will not improve stalk strength directly, rather indirectly by managing foliar diseases. Stalk rots are strongly correlated to disease severity on the flag leaf. When photosynthetic area of the flag leaf is reduced due to pathogen lesions on the leaves, the corn plant cannibalizes the carbohydrates stored in its stalk in order to fill the grain, thereby compromising stalk integrity. Therefore, if you keep the ear leaf clean, you will greatly reduce stalk rots and improve standability, which is where fungicides can help. This is why it is important to scout your fields, look for disease, then determine if a fungicide application is warranted.

Planting corn after corn poses additional risks that favor the development of disease in your crop. By talking into account these steps, hopefully you can better manage your crop and put more dollars in the bank.