Dr. Sarah Potts, Dairy & Beef Specialist

University of Maryland Extension

With temperatures well into the 90s during and heat indices as high as 107°F during these last couple weeks, there’s no doubt that the summer heat has arrived. Making adjustments to management and/or housing of both beef and dairy cattle is crucial to minimizing the negative health and production impacts of heat stress.

Importance of Managing Heat Stress

There is no question that heat stress can negatively impact animal performance. Exposure to heat stress reduces daily gains, milk production, and reproductive efficiency, though specific impacts on production varies depending on the magnitude and duration of heat exposure. Prolonged exposure to heat stress is much more detrimental than short-term heat stress and its effects linger long after temperatures drop back below the heat stress threshold. For example, it can take up to 5 weeks for a breeding bull to recover sperm quality after a bout of mild to moderate heat stress. Exposure to heat stress also reduces oocyte quality and embryo viability, and thus, negatively impacts fertility of the cow. In addition to its effects on fertility, recent studies also indicate that prolonged exposure to heat stress during gestation can have negative, long-lasting impacts on calf performance. A recent study in dairy cattle showed that dairy heifers born to dams exposed to heat stress during the last 2 months of pregnancy were smaller, had a reduced productive life by 5 months, and produced an average of 8 lb/d less during their first 3 lactations than those born to dams who were cooled during the last 2 months of pregnancy. Thus, the value of managing heat stress supersedes the obvious advantages associated with fertility, milk production, and growth.

Signs of Heat Stress in Cattle

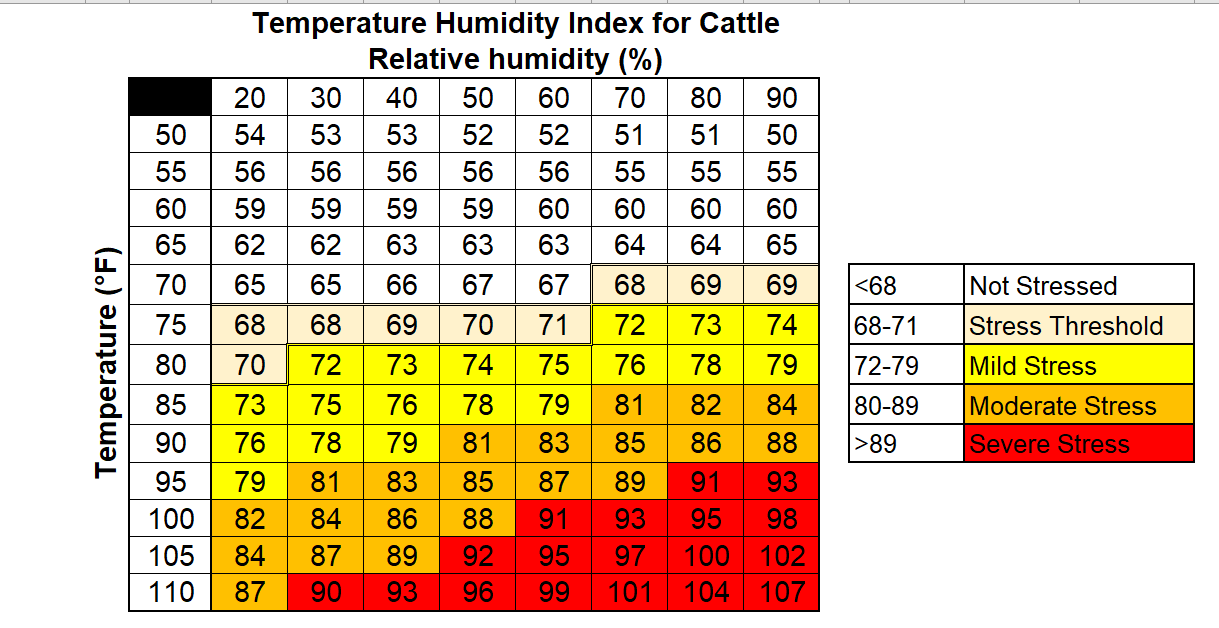

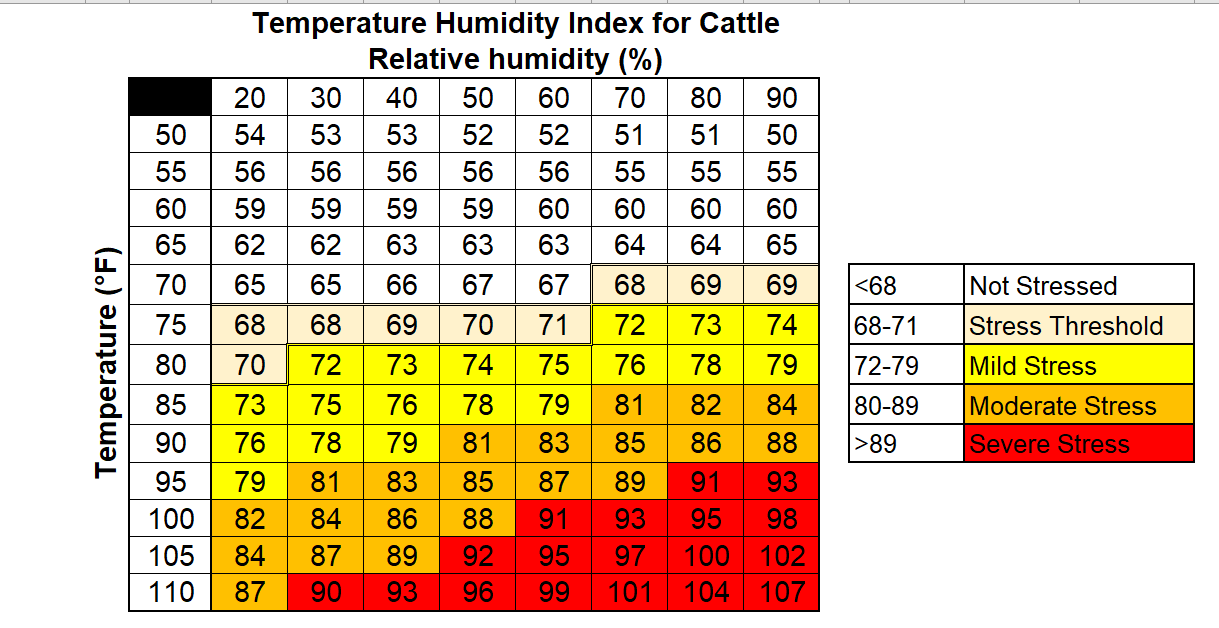

Livestock producers often utilize the Temperature Humidity Index (THI) to assess risk for heat stress, which takes into account both the environmental temperature and humidity. Historically, the gold standard THI threshold for heat stress in cattle is 72. However, recent studies suggest that for high producing dairy cows, the THI threshold should be closer to 68.

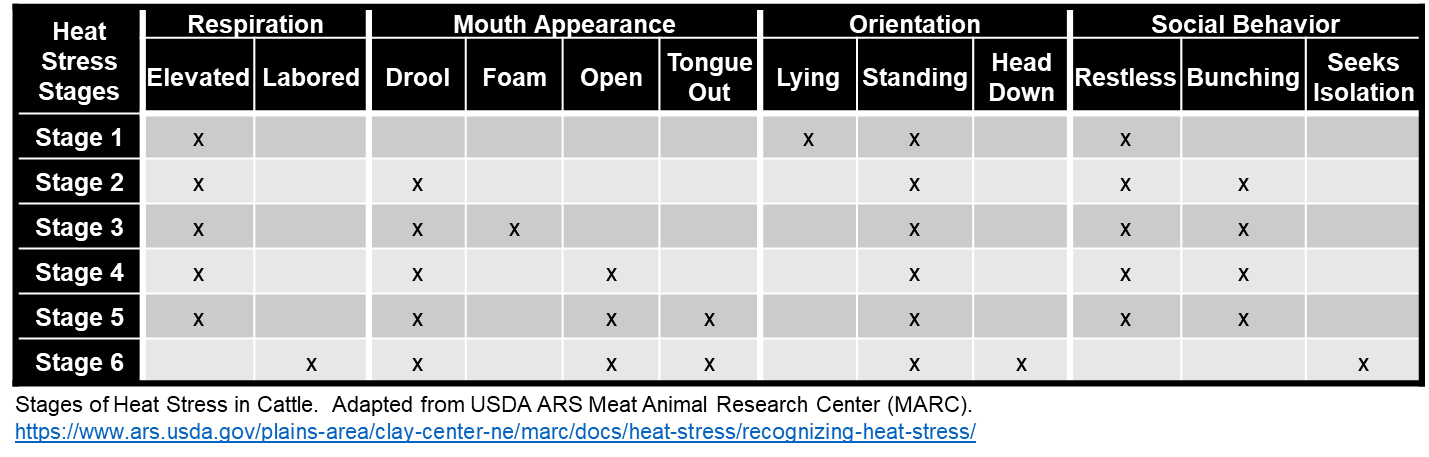

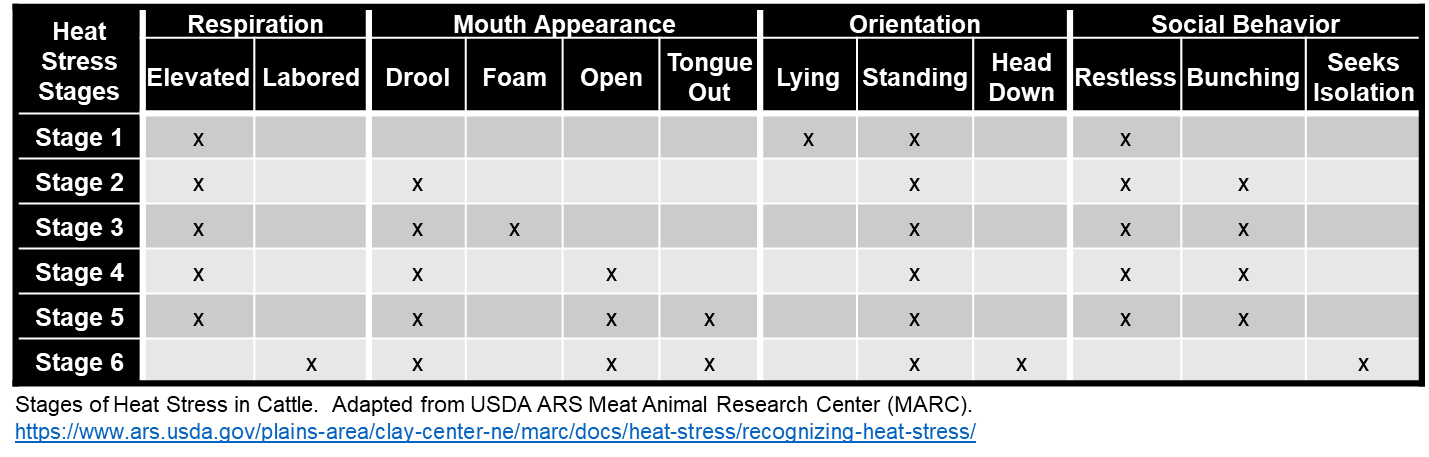

Generally, cattle that are heat stressed will exhibit increased respiration rate and standing behavior, reduced feed intake, and an increase in shade-seeking behaviors. According to the USDA Animal Research Service’s Meat Animal Research Center (MARC), there are six stages of heat stress in cattle which can be identified by various behaviors. Cattle in Stage 6 require immediate attention.

How to Reduce Heat Stress

While there’s a good chance that cattle in our region will experience some degree of heat stress during the summer months, producers should try to reduce the extent and duration of heat stress exposure by making adjustments to their management and housing strategies.

Avoid working animals during the day. Schedule transportation or other activities for early in the morning (preferred) or late in the evening. Any stressful events, such as vaccination, weaning, or dehorning should be rescheduled if there is an impending heat wave.

Ensure ample access to fresh, clean water. Water is required for all animals to maintain body temperature and under normal conditions, a high producing dairy cow will drink up to 50 gallons of water per day, while a beef cow will drink up to 15 gallons per day. Heat stress may cause cattle to increase their water intake up to 50%. Waterers should be installed in areas that are easily accessible for cattle and flow rate should be sufficient to support increased water demand. For dairy cattle, a waterer should be located near the exit of the milking parlor.

Provide shade. This is most basic component of heat abatement and should be provided for all cattle during high temperatures. For confined cattle, this is often in the form of a barn, shed, or shade cloth. Producers with cattle on pasture often rely on natural shade provided by trees. These producers may also consider providing access to a sacrifice area with man made shade during the day and pasture turn-out at night.

Ensure adequate ventilation. Poor ventilation is often an issue inside barns or other man made structures. These facilities should be opened up as much as possible to promote natural airflow by opening side curtains, windows, etc. Fans should also be installed in key areas, such as the feed bunk, over the free-stalls or bedded pack, and holding pen (dairy) to promote airflow.

Consider cooling with water only after there is shade and adequate ventilation. To be effective, this heat abatement strategy must be paired with sufficient airflow or fans to promote evaporative cooling. Simply soaking cattle without adequate airflow will only succeed in creating a more humid environment around the animals. Sprinklers/misters can be strategically placed at the feed bunk and the holding pen (dairy) for optimal cooling.