Laura C. Moore^,*, Alan W. Leslie#, Cerruti RR Hooks$,* and Galen P. Dively+,*

Former graduate student^, Associate Professor and Extension Specialist$, Professor Emeritus+, CMNS, Department of Entomology*, Agriculture Extension Agent, Charles County#

Introduction

Increasing floral diversity within agricultural fields has been proposed as a method to bolster natural enemies and subsequently reduce pest populations. A key factor that enhances predator and parasitoid populations is the availability of nectar and/or pollen food subsidies from flowering plants. Many natural enemies, particularly hymenopteran (wasps) parasitoids, require carbohydrates for successful reproduction and overall fitness. However, monoculture cropping systems are relatively weed-free and generally lack floral resources required by many natural enemies. A literature review showed that the successful establishment of certain parasitoids in cropping systems depended on the presence of nectar-bearing weeds. In addition to providing natural enemies nectar and pollen to eat, flowering plants can supply alternative hosts or prey, shelter, overwintering sites and a more suitable microclimate.

Many conservation projects have been implemented by farmers to increase beneficial services on arable lands. In Maryland, the opportunity to practice conservation biological control exists within the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP). Conservation biological control is a pest management approach that manipulates agricultural systems so as to promote pest suppression by naturally occurring predators, parasitoids and pathogens. The CREP seeks to establish riparian buffers in Maryland to improve water quality, filter sediments and nutrients from runoff and provide wildlife habitat. However, these buffers can be engineered to support communities of natural enemies and serve as corridors for their movement into neighboring crops.

The aim of this study was to determine whether buffer strips could be used as insectary plants to enhance beneficial arthropods (insects and spiders) within neighboring soybeans. Insectary plants are plants grown with cash crops to attract, feed and shelter insect parasitoids and predators so as to enhance their natural control of insect pests. We monitored pest and beneficial arthropods in the buffer insectary plants and neighboring soybean plantings and tried to link arthropods found in buffer plants with pest management in neighboring soybeans.

Abbreviated Experimental Procedures

Insectary buffer test plants. Partridge pea and purple tansy are commonly used to enhance floral resources along field margins for pollinator plantings and to enhance communities of natural enemies in adjacent crops. Partridge pea is a native annual legume and is widely used in seed mixes of CREP riparian buffers because it readily reseeds itself, is competitive when grown with grass mixes, and provides nutritional seed for game birds. As an insectary plant, partridge pea has a long bloom period and each leaf petiole has an extrafloral nectary at its base, which produces nectar throughout the growing season. A diverse assemblage of pollinators and natural enemies are attracted to partridge pea. Purple tansy has a long flowering period, high-quality nectar and pollen production, and is reported as being a valuable insectary plant. Proso millet is a warm season annual grass that lacks floral resources. As such, it served as a grass control to determine how added vegetation diversity in the absence of floral resources would impact natural enemies.

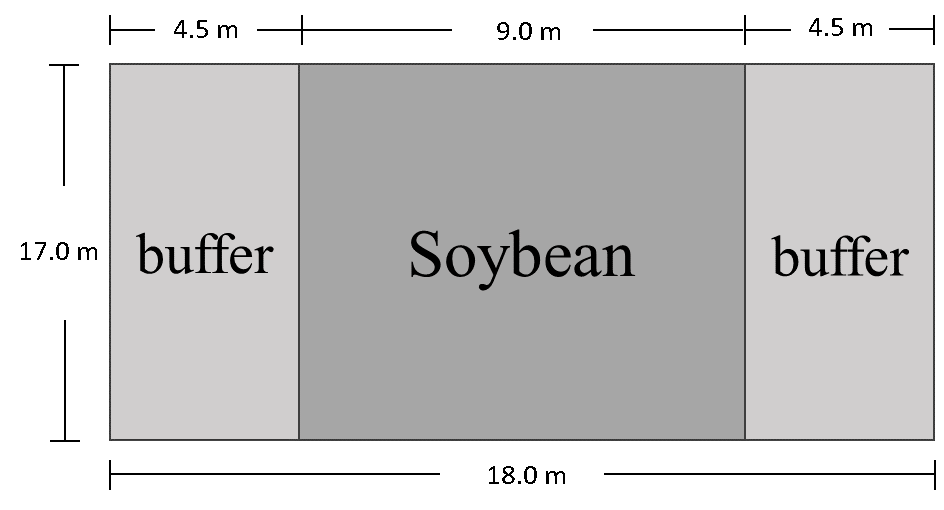

Experimental design. Field experiments were conducted over two years at the Central Maryland Research and Education Center in Beltsville, MD. In year 1, 16 plots of soybean were seeded on May 11. Each plot consisted of 20 soybean rows spaced 35 cm (15 in) apart and bordered on each side by an insectary buffer strip (Fig. 1). The test buffer strips consisted of 1) purple tansy, 2) partridge pea, 3) 50:50 seed mixture of purple tansy + partridge pea, or 4) proso millet. Each soybean plot-buffer combination was replicated four times. Seeds of partridge pea, purple tansy, and proso millet were planted with a no-till drill in rows 23 cm (9 in) apart at a rate of roughly 12,000 seeds per ha (4856 per ac) on the day soybeans were planted.

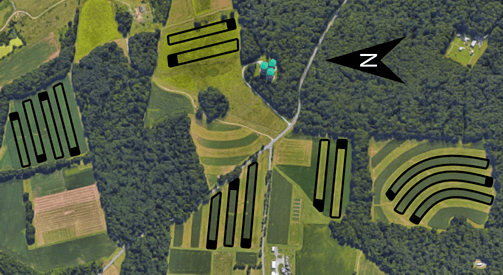

The year 1 study showed that purple tansy was unsuitable for the hot summer conditions in Maryland Thus, it was not used in the year 2 experiment, which focused solely on partridge pea as the insectary buffer plant. The year 2 experiment included 14 strip plantings of full season soybean at five different locations (Fig. 2). Soybeans were planted no-till in 75 cm (30 in) wide rows during May. Each strip was bordered at one end with a partridge pea buffer and at the other end with a mixed grass border of fescue (Festuca spp.) and orchardgrass (Dactylis spp.).

Arthropod population assessments. Abundances of arthropods active in the plant canopy were measured with yellow sticky cards secured to bamboo poles. Further, sweep-net samples were taken in July and August to estimate green cloverworm (Hypena scabra) numbers. The green cloverworm served as a bioindicator of changes in pest populations potentially caused by enhanced natural enemy activity. The larger field size in year 2 allowed sticky cards to be placed throughout the soybean strip. One card was placed in the center of each partridge pea buffer, and additional cards were placed at distances of 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 m (10 ft to 79 ft) from the border on both sides of each soybean strip (total of 10 sticky cards per strip). Sampling was conducted weekly or biweekly. In year 2, pitfall traps were also installed in the ground adjacent to each sticky card to estimate the abundance of surface-dwelling arthropods over 7-day intervals.

Summary of Results

Year 1 Study – comparison of four insectary buffers parasitoid abundance. Three families of parasitoids Mymaridae, Scelionidae and Trichogrammatidae comprised 83.9% of the total of parasitic wasps captured on sticky cards. Families Ceraphronidae, Braconidae and Eulophidae comprised an additional 12.5% of the wasp parasitoid group. Of these parasitoids, mymarids were the most abundant and there were 73-78% higher sticky card captures of this wasp in partridge pea compared to purple tansy and millet buffers. However, significantly fewer mymarids were captured in soybeans adjacent to partridge pea than adjacent to purple tansy or millet. Scelionid parasitoids were more abundant in millet and purple tansy buffers but their numbers were similar in soybeans regardless of the neighboring buffer type. Trichogrammatid abundance was greatest in millet early in the season and in buffers with partridge pea by season end. Two families of fly parasitoids (Tachinidae and Sarcophagidae) averaged 9.4 and 4.4 flies per sticky card in insectary buffers and soybean plots, respectively. The abundance of sarcophagid flies was significantly higher in buffers with partridge pea than millet or purple tansy alone. Similarly, soybeans adjacent to partridge pea were inhabited by more tachinids and sarcophagids than soybeans adjacent to millet or purple tansy.

Predator abundance. Overall predator abundance was significantly higher in purple tansy and millet compared to partridge pea or mixed (partridge pea + purple tansy) buffers. Mean captures per card were 5.0 in partridge pea, 6.8 in mixed, 8.5 in purple tansy, and 10.3 in millet. However. similar predator numbers were captured in soybean plots adjacent to all four buffer types.

Insect herbivores (plant feeders). Sweep net counts of green cloverworm were statistically similar in soybean plots adjacent to the four different buffer types. Overall numbers per 10 sweeps averaged 24.6, 27.0, 18.0, and 23.0 in soybeans adjacent to millet, purple tansy, mixed and partridge pea buffers, respectively. The bulk of other insect herbivores captured on sticky cards were mainly aphids, leafhoppers, planthoppers and plant bugs. Mean numbers captured per card were 86.1 (millet), 113.2 (purple tansy), 57.6 (mixed) and 53.7 (partridge pea).

3.2. Year 2 Study partridge pea vs. natural grass vegetation

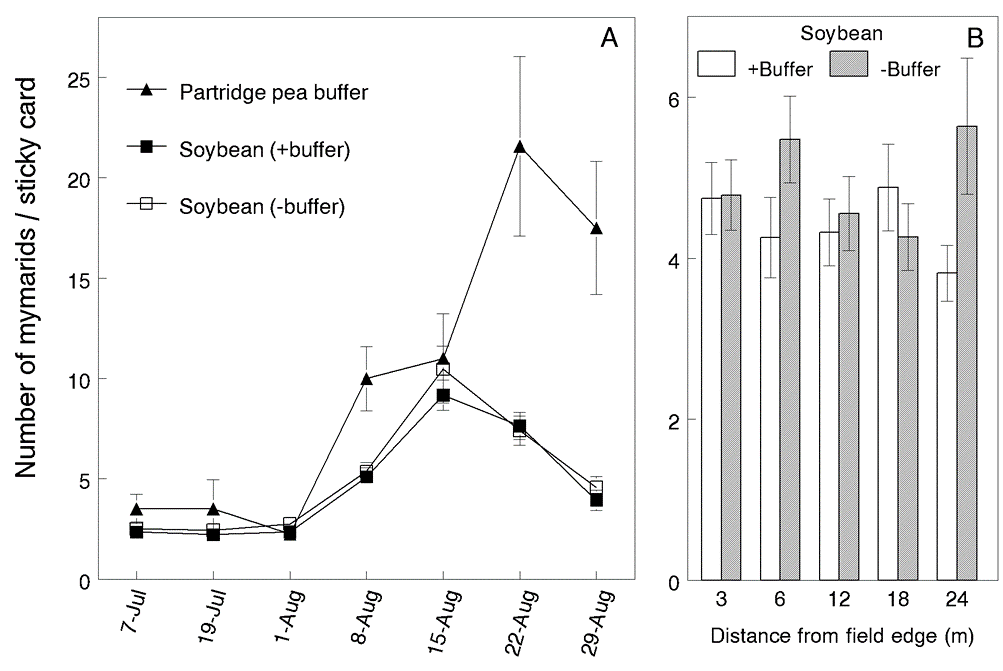

Parasitoid abundance. The most abundant parasitoids belonged to families Mymaridae, Trichogrammatidae and Scelionidae in order of abundance, and together comprised 84.3% of the total hymenopteran parasitoids captured. Each family responded differently to the partridge pea treatment. Mymarid abundance was higher overall in partridge pea buffers but did not enhance their abundance in neighboring soybeans (Fig. 3). Significantly fewer trichogrammatids were captured in partridge pea compared to numbers captured in soybean with and without the partridge pea buffer. Mean captures of dipteran parasitoids per sticky card abundance were significantly higher in soybean neighboring partridge pea, with the exception of the first and last sampling dates.

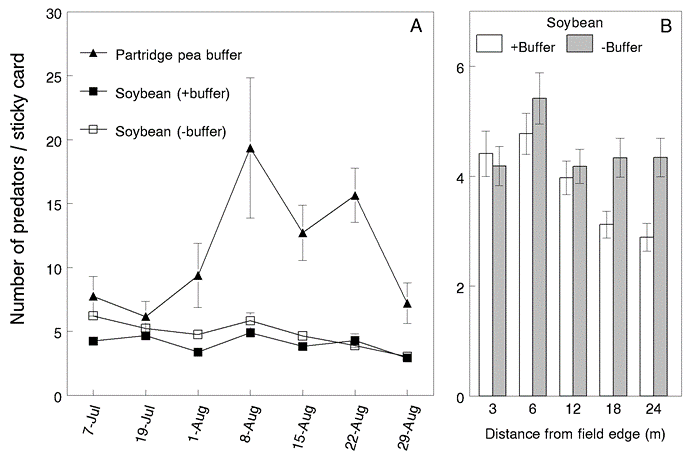

Predator abundance. Long-legged flies, minute pirate bugs, and big-eyed bugs comprised 81.4% of the total predatory arthropods captured. Soldier beetles, fireflies and lady beetles represented an additional 11.6%. Mean abundance of predators per sticky card was 11.5 ± 1.1 in buffer, 4.1 ± 0.16 in soybean neighboring buffer and 4.9 ± 0.18 in soybean without buffer. Abundance of predators was significantly lower in soybean neighboring the partridge pea buffer (Fig. 4). However, this was largely due to the activity of long-legged flies, which were more attracted to the partridge pea buffer. Still, their numbers were significantly lower in soybean strips neighboring partridge pea compared to soybeans without partridge pea buffers.

Insect herbivores/pests. Thrips, leafhoppers, treehoppers, froghoppers and planthoppers comprised over 95% of herbivores captured on sticky cards. The total number of herbivores per sticky card averaged 108.2 in the partridge pea buffer, 96.3 in soybean neighboring buffer, and 96.4 in soybean without buffer. Thus, herbivore numbers did not differ significantly in the buffer and soybeans.

Pitfall trap predators. A total of 56,296 arthropods were identified from pitfall trap samples. Of predators captured in pitfall traps, ants, spiders, soldier beetle larvae, rove beetle adults and larvae, and ground beetle adults and larvae were the most abundant. Ant numbers were significantly lower in soybeans neighboring partridge pea on all sampling dates.

Discussion

Year 1 study was conducted to determine if pure and mixed buffer strips of partridge pea and purple tansy could attract greater numbers of beneficial arthropods than non-floral strips of millet, and whether these buffers enhance beneficial arthropod abundance in neighboring soybeans. Purple tansy was not a suitable insectary plant as it was not well adapted to the seasonal period of the study in Maryland. Furthermore, purple tansy would probably be less desirable to establish and maintain as a buffer strip due to its relatively high seed price, slow growth characteristic and greater susceptibility to weed competition. Moreover, purple tansy was quickly out-competed by partridge pea in the mixed planting to the extent that the pure and mixed buffers containing partridge pea attracted similar arthropod communities.

Overall, results consistently showed that partridge pea attracted and supported high populations of natural enemies and potential hosts and prey, with abundances significantly greater than levels found in adjacent soybeans. Sticky card captures of wasp and fly parasitoids in year 1 were more than 70% higher overall in buffers containing partridge pea compared to other buffer types. Similarly, populations of all beneficial arthropods captured by sticky card and pitfall sampling in year 2 were approximately 80 to 72% higher, respectively, in partridge pea buffers compared to the soybean crop.

Parasitoids. Mymarid wasps were notably the most common parasitoids captured on sticky cards and consistently more abundant in partridge pea compared to soybean. These tiny wasps parasitize insect eggs in concealed sites within plant tissues or the soil and are important natural control agents of economically important leafhopper pests. In year 1, mymarids reached levels in partridge pea buffers that were four-fold higher than those in soybean plots, yet significantly lower levels of mymarids were captured in soybean adjoining these buffers. This suggests that the partridge pea lured mymarids from neighboring soybeans. High numbers of mymarids were also captured in partridge pea in year 2 but their abundance in soybeans was not enhanced. This suggests that partridge pea may provide some parasitoids and their associated hosts with all resources required for survival and reproduction. This would in effect provide no incentive for these parasitoids to forage within neighboring crops.

Most fly parasitoids found on sticky cards were tachinids or sarcophagids. The vast majority of hosts of tachinid flies are plant-feeding insects. Their level of parasitism can vary greatly, from less than 1% to approaching 100%, depending on such factors as the size of a host and parasitoid population, and environmental conditions. During both study years, their overall abundance in partridge pea was 62.3% higher than levels in soybean. In year 2, this effect was heightened at the field edge next to buffers, suggesting that higher numbers of parasitic flies encroached into the neighboring soybeans but enter only a short distance within the crop.

Predators. In year 1, predators captured on sticky cards were 65% more abundant in the millet and purple tansy buffers. This response was mainly attributed to the abundance of long-legged flies. These predatory flies hover while searching for small, soft-bodied arthropods, particularly other flies, aphids, spider mites, larvae of small insects and thrips. However, abundances of long-legged flies in soybean plots were not affected by buffer type in year 1. Long-legged flies were also the predominant predators active in the plant canopy in year 2, with overall numbers 2-3 times higher in partridge pea buffers compared to levels found in soybeans. However, their abundance was significantly lower in soybean neighboring partridge pea, particularly at sampling sites closest to the field edge. This is further evidence that the partridge pea acted as a natural enemy sink.

Of the ground-dwelling predators captured by pitfall traps, ants were the predominant group and their abundance was significantly higher in partridge pea than adjoining soybeans. Their numbers were significantly lower in soybean plantings adjacent to partridge pea than grassy check treatment on all sampling dates, implying again that partridge pea acted as a natural enemy sink by luring ants away from soybean. Populations of other ground-dwelling predators, which consisted mainly of spiders, rove beetles, soldier beetles and ground beetles, showed a definite preference for partridge pea compared to soybeans. However, their abundances in the crop were not affected by partridge pea presence.

Herbivores. Sticky card captures each study year indicated that partridge pea harbored significantly more insect herbivores compared to soybean. The majority of herbivores were aphids, leafhoppers, planthoppers and plant bugs. In year 1, number of green cloverworm, as well as other herbivores in soybean were similar regardless of the buffer treatment.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that partridge pea provides floral resources and alternative food for a diverse community of natural enemies and herbivores. However, its presence as a monoculture buffer did not result in increased number of major natural enemies in neighboring soybeans. Taken together, partridge pea planted as a monoculture acted more as a natural enemy sink by attracting beneficial arthropods away from soybean, potentially decreasing natural control efforts. For this reason, a monoculture of partridge pea may not be an ideal insectary planting if the ultimate goal is to maximize natural enemy efficacy in neighboring soybean fields.

In conservation reserve practices, monocultures of partridge pea are more commonly planted as a wildlife habitat to provide food for bobwhite quail and other wildlife and as flowering habitat for different pollinator taxa. Because the foliage is potentially poisonous to cattle and re-seeding plants can aggressively fill in voids when used as part of a seed mix, conservationists recommend for herbaceous riparian buffers that the total seed mix consist of no less than 1% and no more than 4% partridge pea. However, decisions about the deployment of insectary plants as a monoculture or part of a riparian buffer mix planting should take into consideration the attractiveness and resources provided to natural enemies and their hosts/prey by the insectary habitat in comparison to those provided by the neighboring cash crop. Simple addition of a highly attractive flowering buffer adjacent to a crop could be counterintuitive to natural biological control efforts.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for field studies and publishing results was provided by the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Grants Program, Maryland Soybean Board and USDA NIFA EIPM grant number 2017-70006-27171.