Maria Cramer, Edwin Afful, Galen Dively, and Kelly Hamby

Department of Entomology, University of Maryland

Overview

Background: Due to their low cost, pyrethroid insecticides are often applied when other chemical applications are made. For example, they may be included in tank mixes with herbicides in early whorl corn and with fungicides during tasseling. These pyrethroid sprays often target stink bugs; however, the timing of these treatments is not ideal for stink bug management. Pyrethoid insecticides may harm beneficial insects that help keep pest populations in check and repeated use of pyrethroids can contribute to insecticide resistance.

Methods: In this study, we examined the effect of Bifenture EC® (pyrethroid active ingredient: bifenthrin) applied with herbicides in V6 corn and with fungicides in tasseling corn. We evaluated impacts on pests and beneficials at both application timings. Yield was measured at harvest.

Preliminary Results: At both application timings, Bifenture EC® did not improve insect pest management because pests were not present at economic levels. We did not find evidence for flare-ups of aphids or spider mites, but a rainy late summer made it unlikely that we would see many of these pests. There were no yield differences between the treatments.

Background

As a result of the low cost of pyrethroid insecticides, preventative applications are common, especially in tank mixes with other routine chemical inputs, such as herbicides and fungicides. However, lower grain prices and low insect pest pressure make it less likely that pyrethroid applications will provide economic returns. Bt hybrids1 and neonicotinoid seed treatments control many of the pests targeted by pyrethroid insecticides. Because they have broad spectrum activity, pyrethroids can negatively impact natural enemies2 which can result in flare-ups of secondary pests3. Tank mix timings may be less effective than applying when insect populations reach threshold. For example, when pyrethroids are combined with herbicide applications, they are too late to control early-season stink bugs and other seedling pests. When pyrethroids are combined with fungicide sprays at tasseling, few insect pests are present at damaging levels. Stink bugs may feed on the developing ear at this time, causing deformed “cowhorned” ears; however, this is rarely a problem in Maryland and stink bug damage is generally not economic throughout a field because feeding is primarily concentrated at the field edge4. Insecticide applications at tasseling have a high potential to affect beneficial insects, especially pollinators and natural enemies that are attracted to corn pollen.

Objectives: Our objectives were to determine the effect of pyrethroids applied preventatively in tank-mixes on corn pests, beneficials, and yield.

Methods: This study was conducted in 2018 and 2019 at the University of Maryland research farm in Beltsville, MD. For each application timing, we planted four replicate plots of a standard Bt field corn hybrid, DeKalb 55-84 RIB (SmartStax RIB complete Bt insect control in addition to fungicide and insecticide seed treatments) at 29,999 seeds per acre. Standard agronomic practices for the region were used.

The herbicide timing compared two treatments:

- Herbicide alone (22 oz/acre Roundup WeatherMAX®, 0.5 oz/acre Cadet®, 3 lb/acre ammonium sulfate

- Herbicide (same as above) + Insecticide (Bifenture EC® 6.4 oz/acre)

Treatments were applied at V6/V7. We visually surveyed corn plants for pest and beneficial insects before and after application. We also placed sentinel European corn borer (ECB) egg masses in the field to assess predation rates before and after treatment.

The fungicide timing compared two treatments:

- Fungicide alone (Trivapro® 13.7 oz/acre)

- Fungicide (same as above) + Insecticide (Bifenture EC® 6.4 oz/acre)

Treatments were applied at green silk. We inspected the ear zone and silks for pests and beneficial insects before application. After application, we recorded the number of ears with pest damage and the kernel area damaged. We also counted stink bug adults and cowhorned ears. Six weeks after application, we visually assessed plants for spider mite and aphid colonies.

Results

In the herbicide-timing study in 2019 we observed no effect on beneficial insects from the treatments (Figure 1). The most abundant beneficial species were minute pirate bugs and pink spotted lady beetles, which are very mobile and may have recolonized treated plots after treatment. Similarly, treatments did not affect predation on the sentinel egg masses, suggesting that the pyrethroid application may not have affected predators’ ability to locate and consume eggs. Across the treatments, 30-50% of egg masses were consumed by predators.

The treatments did not impact the number of beneficials at the herbicide timing (N.S.). The pyrethroid insecticide significantly reduced the number of plant hoppers and plant bugs from less than 4 per plant on average to less than 2 per plant (significantly different p<0.05, *), though these insects are not economic pests at this stage. There were never more than 2 stink bugs per 90 plants, well below the treatment threshold of 13 per 100 plants4.

In the fungicide-timing study in 2019, beneficials, especially minute pirate bugs, were abundant at the time of application (3 in every 10 plants), while stink bugs, the presumed target pest, were very rare (1 stink bug in every 68 plants). In 2018, stink bugs were similarly scarce. Overall pest abundance was low (1 in every 35 plants). After application, there was no difference in the incidence or amount of the corn ear damaged by worms, stink bugs, or sap beetles between treatments. Average stink bug and earworm incidence was roughly 1 in 10 ears, while sap beetle was even less frequent. Cowhorned ears and adult stink bugs were almost non-existent in both treatments.

Six weeks after application we found no differences in aphid or spider mite populations between the treatments, suggesting that pyrethroid applications at tasseling did not cause secondary pest outbreaks. We sampled after a period of dry weather; however, the late summer was rainy at Beltsville, which likely suppressed spider mite and aphid populations. Under drought-stress, reductions in the natural enemy population from pyrethroid use might contribute to flare-ups of aphids and spider mites.

Yield

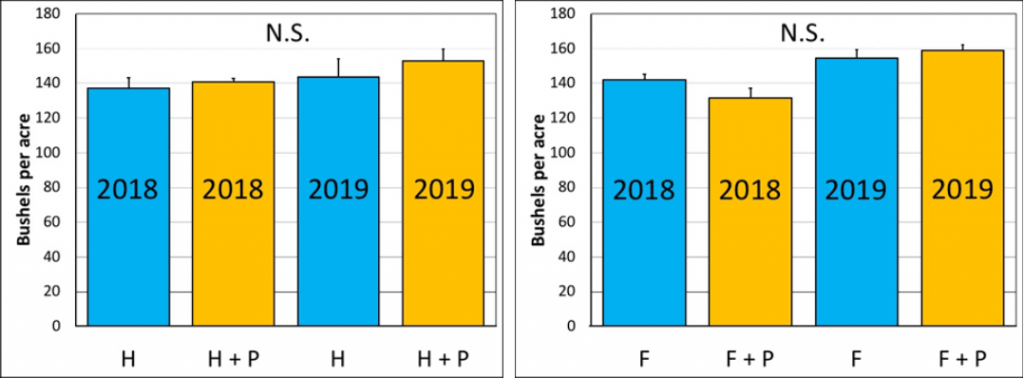

For the herbicide timing and fungicide-timing (Figure 2) studies, treatments did not affect yields in either 2018 or 2019.

Conclusions

Results from the 2018 and 2019 studies suggest that pyrethroid applications do not provide yield benefits in corn when tank-mixed with herbicides or fungicides, likely due to the lack of insect pest pressure at these spray timings. Beneficial insects were abundant in the crop at each of these timings and did not appear to be affected by the pyrethroids in the herbicide plots. Repeated preventative use of pyrethroids in the same field could potentially hinder the natural biocontrol of corn pests.

Sources

1 DiFonzo, C. 2017. Handy Bt Trait Table for U.S. Corn Production, http://msuent.com/assets/pdf/BtTraitTable15March2017.pdf

2Croft, B.A., M.E. Whalon. 1982. Selective toxicity of pyrethroid insecticides to arthropod natural enemies and pests of agricultural crops. Entomophaga. 27(1): 3-21.

3Reisig, D.C., J.S. Bacheler, D.A. Herbert, T. Kuhar, S. Malone, C. Philips, R. Weisz. 2012.Efficacy and value of prophylactic vs. integrated pest management approaches for management of cereal leaf beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in wheat and ramifications for adoption by growers. J. Econ. Entomol. 105(5): 1612-1619

4Reisig, D.C. 2018. New stink bug thresholds in corn, https://entomology.ces.ncsu.edu/2018/04/new-stink-bug-thresholds-in-corn/