Amanda Grev, Pasture & Forage Specialist

University of Maryland Extension

Along with making corn and soybean planting a challenge, spring rains make for a challenging forage harvest as well. The faster we can get our hay or haylage dry enough to bale or wrap, the more we can reduce the risk of rain damage and retain a higher quality end product. Follow these guidelines to help optimize drying time during forage harvest this spring.

The Forage Drying Process

Let’s think for a moment about the basic principles behind forage drying. When forage is cut, it is around 75 to 80% moisture but it must be dried down to 60 to 65% moisture for haylage or 14 to 18% moisture for dry hay. During this wilting and drying process, plants continue the natural process of respiration, breaking down stored sugars to create energy and carbon dioxide. The longer it takes the forage to dry, the longer the forage continues to respire in the field. Data suggests that 2 to 8% of the dry matter may be lost due to respiration, resulting in energy losses and an overall reduction in forage quality. This means that a faster drying time will not only get the forage off the field faster but will also lower the amount of dry matter and nutrients lost through respiration.

The drying process happens in several distinct phases; knowing and understanding these phases can help us manage our forage in a way that will maximize drying rates and ensure nutrient retention within the harvested forage.

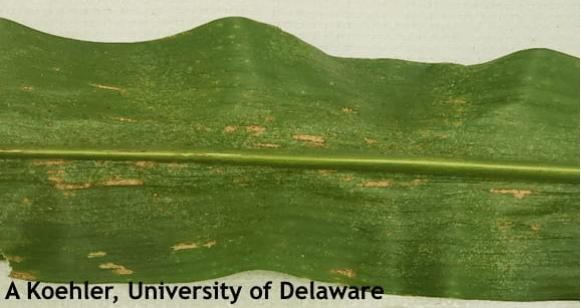

Phase One: Moisture Loss via Stomatal Openings

The first phase in the drying process is moisture loss from the leaves. This happens through the stomata, which are the openings in the leaf surface that allow for moisture and gas exchange between the leaf and the outside air. These stomata are naturally open in daylight and closed in darkness. After a plant is cut, respiration continues but gradually declines until the moisture content has fallen below 60%. Rapid drying in this initial phase to lose the first 15 to 20% moisture will reduce loss of starch and sugar and preserve more dry matter and total digestible nutrients in the harvested forage.

Solar radiation is the key to maximizing drying during this initial phase. This can be accomplished by using a wide swath (at least 70% of the cut area), which will maximize the amount of forage exposed to sunlight. A wider swath will increase the swath temperature, reduce the swath humidity, and keep the stomata open to allow for moisture loss, encouraging rapid and more even drying immediately after cutting. In contrast, narrow windrows will have higher humidity and less drying, allowing respiration to continue and leading to further dry matter and nutrient losses. Research has shown that a wide swath immediately after cutting is the single most important factor in maximizing the initial drying rate and preserving digestible dry matter. A full width swath will increase the drying surface of the swath by 2.8 times, and moisture reductions from 85 to 60% can be reached in as little as 5 to 7 hours. Haylage from wide swaths has been shown to have lower respiration losses during drying, greater total digestible nutrients, and more lactic and acetic acid, improving forage quality and fermentation.

During this phase, a wide swath is more important than conditioning. Most of the respiration takes place in the leaves. While conditioning is important for drying stems, it has less impact on drying leaves and therefore will have little effect on this initial moisture loss. This means that for haylage, a wide swath may be more important than conditioning.

Phase Two: Stem Moisture Loss

The second phase in the drying process includes moisture loss from the stems in addition to the leaves. Once moisture levels have dropped to the point where plant respiration ceases, the closing of the stomata traps the remaining moisture, slowing further drying. At this stage, conditioning can help increase the drying rate because it provides openings within the plant’s structure, providing an exit path for moisture and allowing drying to continue at a faster rate. For maximum effectiveness, be sure the conditioner is adjusted properly based on the stem thickness (roughly 5% of leaves showing some bruising) and choose the best conditioner based on your forage type. For example, roller conditioners are often preferred for alfalfa due to reduced leaf loss.

Phase Three: Loss of Tightly Held Water

The final phase of the drying process is the loss of tightly held water, particularly from the stems. Stems generally have a lower surface to volume ratio, fewer stomata, and a semi-impervious waxy cuticle that minimizes water loss so conditioning is critical to enhance drying during this phase.

Additional Factors

In addition swath width and conditioning, several other strategies can be used to improve drying time. Be sure to cut forages at the proper height, leaving 2 to 3 inches for alfalfa and 4 inches for cool-season grasses. Not only will this result in improved stand persistence, earlier regrowth, and sooner subsequent cuttings, but the stubble will help to elevate the swath and promote air flow and rapid drying. If possible, mow hay earlier in the day, preferably mid- to late-morning after the dew has dried off. This will allow for a full day of drying right away, maximizing exposure to sunlight and resulting in a faster drop in moisture and reduced respiration. And finally, raking should occur when the forage is above 40% moisture. Raking the forage while it is still pliable helps to reduce leaf loss and maintain forage quality. Adjust the rake to minimize the amount of tines touching the ground to avoid soil contamination.

In conclusion, cutting in the morning and using wide swaths to take advantage of sunlight is key to both faster drying and preserving digestible dry matter. Remember, a wide swath enhances leaf drying while conditioning expedites stem drying; both are needed to make high quality hay.