Amanda Grev, Pasture & Forage Specialist

University of Maryland Extension

Fertilizer prices have continued to climb, with prices increasing as much as 89 to 154% from the end of 2020 through the beginning of 2022 (Figure 1). Current predictions are that fertilizer prices are expected to remain elevated for the time being, putting us well into the growing season.

Given these high prices, it is essential to think carefully about nutrient management programs and making smart choices when it comes to fertilizer and nutrient decisions. Rather than blindly cutting expenses, we need to look for those places where eliminating costs will have little or no impact on forage production. Below are some strategies to consider that may help reduce the impact of high fertilizer prices on your bottom line.

Start with What You Have

Regardless of whether your operation uses conventional or organic practices, there are basic physical and chemical limitations to forage production within your fields. We know that suboptimal protein or energy in the ration will limit milk production or animal gains; in the same way, suboptimal nutrients in the soil will limit forage production. That said, there is no reason to apply nutrients where they are not needed, especially when prices are high. When a particular field contains high or very high levels of certain nutrients, there is no real economic return on adding additional nutrients. In fact, high or excess nutrient levels can even limit profitability in some cases by tying up other nutrients and causing deficiencies.

What is needed in terms of nutrients will vary tremendously from farm to farm, from field to field, and from crop to crop. You can’t balance the soil without knowing what is available, and the only way to determine existing nutrient levels is through soil testing. While soil tests may not be perfect, we can’t manage what we haven’t measured, and knowing the nutrient content of forage fields is a critical step in being able to target nutrient applications to fields which will give us a positive economic response.

Prioritize Based on Nutrient Status

Once we have our soil test results, we can use the information to prioritize fields based on their current nutrient status. For nutrients other than nitrogen, fertilization decisions for each field should be determined in relation to whether the field is below, within, or above the optimum range.

Fields that already contain optimum nutrient levels can likely get by with less, or in some cases, no added fertility. Under normal circumstances, it is typically recommended that fields in the optimum range receive nutrients at a level equal to crop removal rates to maintain soil nutrient levels in the optimum range for the future. However, it is not always necessary to pre-replace the nutrients that will be utilized. Soils in the optimum range should have enough nutrient supplying capacity to grow crops without any deficiency for at least a year. This is especially true for soil phosphorus reserves, which can often last for several years; soil potassium reserves tend to be depleted faster, especially where forage crops are harvested. Therefore, we can rely on the existing soil nutrients for now and replace the removed nutrients later on when fertilizer prices are lower. Keep in mind that you can’t rely on this forever; eventually, soil test levels will fall below optimum, yields will suffer, and forage stands will weaken and thin. This is especially true for hay production, which has a much higher soil nutrient removal compared to pasture. However, this strategy can be used to get through temporary price spikes and supply shortages if your soil test levels are in the optimum zone to begin with. If fertilizer prices remain high over the next year, consider getting a new soil test next year to make sure you haven’t fallen below the optimal range, and adjust your fertilization strategy according to the new results.

For fields with soil test levels below the optimum range, investing in added nutrients is often warranted due to the high probability of a positive economic response; if not added, there is an increased likelihood of yield or stand declines resulting from nutrient deficiencies. However, remember that fertility recommendations for fields that test below the optimum range typically call for enough nutrients to supply the crop with what it will remove in a given year while also adding additional nutrients to raise the soil test level up into the optimum range. In times when fertilizer prices are high, focus on providing the crop with a maintenance level of fertility equal to what it will remove each year, and wait to build fertility levels back up into the optimum range for another year when prices are lower. Crop removal rates can be calculated based on the expected yield multiplied by the average removal rate for each unit of yield (Table 1).

Table 1. Typical crop removal rates per ton of forage produced for nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K).

| Crop | N Removal | P2O5 Removal | K2O Removal |

| ____________ Uptake, lbs/ton ____________ | |||

| Alfalfa | 56 | 15 | 60 |

| Orchardgrass | 50 | 17 | 62 |

| Tall Fescue | 39 | 19 | 53 |

| Timothy | 37 | 14 | 62 |

| Bermudagrass | 43 | 10 | 48 |

| Sorghum-Sudangrass | 40 | 15 | 58 |

Ensure Maximum Nutrient Availability

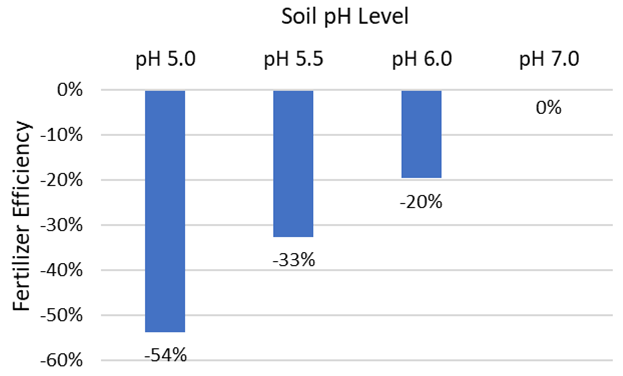

Regardless of soil nutrient status, the amount of fertilizer available to the plant is optimized by having the pH correct for the crop. Maintaining an optimum soil pH aids in the availability of other nutrients, ensuring that we are getting the most out of the nutrients present in the soil. As soils become more acidic, nutrients become less available to the plant, even if they are present in the soil. This can result in a 20 to 50% decrease in fertilizer efficiency with declining pH levels (Figure 2). This means that at a pH below 6.0, you are essentially throwing away 20% or more of your fertilizer due to the effect of soil acidity on nutrient availability.

Unlike many other nutrients, lime prices have remained relatively stable. Correcting soil pH and maintaining it in the optimum range (6.0 to 7.0 for most forage crops) allows for maximum nutrient availability for most macro and micronutrients and is one of the biggest things you can do to prevent this and get the most bang for your fertilizer buck. An added benefit, maintaining an optimum soil pH also helps maintain a strong legume component in mixed stands, which in turn provides a cheap source of nitrogen for grass growth.

Pick the Right Product

Fertilizer efficiency depends on the type of product being used. Blended fertilizers like 10-10-10 or 13-13-13 may be easier to apply but may not provide the forage with enough of a given nutrient or may result in the application of unneeded nutrients. Particularly for harvested forages, these straight blends are likely not sufficient to replenish the K being removed from the hayfield. Getting a custom blend or mixing fertilizer may be more tedious, but it can be better tailored to the needs of the crop and field, reducing inputs and also preventing over-application of expensive and unneeded nutrients.

Use Legumes to Your Advantage

One of the most cost-effective ways to add nitrogen into hay or pasture systems is through the addition of legumes. Due to their symbiotic relationship with soil rhizobium bacteria, legumes have the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia that can be used by the plant. This capability allows legumes to fix anywhere from 50 to 250 pounds of nitrogen per acre per year, which translates to a big savings at current nitrogen prices. If an adequate level of legumes is present in forage stands (typically at least 30% or greater), you may be able to effectively eliminate the need for additional nitrogen, while also providing other benefits such as increased forage quality and improved summer production.

One easy way to increase the legume component of a forage stand is through frost seeding. This seeding method uses the natural freezing and thawing actions of the soil to work seeds into the soil where they can germinate as temperatures warm. Clover is typically the most successful species to frost seed, but annual lespedeza may be another option. If you missed the frost seeding window, drilling legume seeds into pastures during the spring or fall is also an option. Either way, for successful legume establishment be sure that soil fertility levels (particularly soil pH) are adequate and the seed is inoculated with the proper bacterial inoculant.

Be Strategic with Nitrogen

For stands without legumes, nitrogen is still a key player in maximizing production. However, we can be strategic with our timing and number of applications. Strategic timing for nitrogen might mean forgoing an early spring application, as it’s not uncommon to have excess forage available on pasture in the spring or to grow more first cutting hay than can be made and harvested in a timely fashion. However, nitrogen applied to a grass hayfield immediately after first or second cutting can significantly boost the yield of the subsequent cutting. Similarly, late fall nitrogen applications on cool-season perennial forages have been proven to help increase plant density, improve winter survival, and promote green up earlier in the spring. Bottom line, before you feel the need to add nitrogen to increase yield, make sure you will be able to effectively utilize the additional forage produced and do some calculations to make sure your nitrogen application is warranted and economical at the current prices.

Capitalize on Manure as an Alternative Nutrient Source

Although the need for nutrients by plants can’t be changed, the source of those nutrients can be. Most producers recognize the value of livestock manure as a plant nutrient source. Applying this manure, either by spreader or by animal, in the right place, at the right time, and in the right amount can go a long way to reducing fertilizer expenses.

Manure can provide significant amounts of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, making it a valuable source of nutrients. However, there is a huge range in nutrient content depending on species, farm, and management conditions. Manure samples will give you the data you need to know what you are working with in terms of nutrients. As an example, poultry litter containing 2.7% N, 2.3% P2O5, and 2.9% K2O would provide 54 lbs N, 46 lbs P2O5, and 58 lbs K2O per ton. Altogether, this adds up to a total of around $117 per ton in nutrient value based on current fertilizer prices. If you were to spread 2 tons per acre, this means you are effectively applying $234 per acre, which is a big savings over fertilizer prices. Now is not the time to spread manure on the most conveniently located field. Rather, apply it where the soil test indicates it’s most needed. Manure applications should be prioritized on fields that require nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to maximize utilization of all three nutrients. If your soil tests are already optimum or above optimum in phosphorus and potassium for certain fields, consider applying manure to other fields that are in need of those nutrients.

Note that not all of the nitrogen in manure will be immediately available to plants. The amount available varies based on manure source, type of application, and weather patterns, but on average approximately 45 to 65% of the nitrogen in manure will be available during the first year following application, with more becoming available over time as the organic fraction is made available through mineralization.

Manure can be equally as valuable in a pasture situation. In a grazing system, as much as 80 to 90% of the nutrients consumed by the animal are recycled back into the system. However, there is a tendency for nutrients to become concentrated near shade and watering areas, so it becomes critical to ensure an even distribution of nutrients from animal manure. This is best accomplished by implementing rotational grazing and by using a winter feeding system that doesn’t involve a centralized feeding area; both of these strategies will help distribute nutrients more evenly across the pasture area.

Minimize Losses

The most common nitrogen source used for pastures and hayfields is urea, which is prone to volatilization losses when left on the soil surface. Applying nitrogen after a first cutting onto warm soils at times of high air temperature increases the risk of volatilization when using urea-based nitrogen sources. If urea is being used, applying prior to a rain event can help mitigate these losses. If rainfall is not expected, including a nitrogen stabilizer or urease inhibitor may be warranted; however, this will be an added expense. Alternatively, if other nutrients are needed at the same time, the nitrogen that comes along with a phosphorus source like DAP (18-46-0) is more stable, as are other options like ammonium sulfate (21-0-0-24).

Similarly, efforts should be made to maximize efficiency and minimize losses of the nutrients contained in manure. As much as 50 to 75% of the available nitrogen in manure can be lost through nitrogen volatilization and runoff losses when manure is surface applied, meaning you now have to make up for that in other ways or put more manure on to meet your nitrogen needs. If it is an option and fits within your management, consider incorporating or injecting your manure to minimize nitrogen losses. This will allow you to hold on to the ammonia nitrogen in addition to the organic nitrogen, and will also prevent uneven applications due to movement down into swales or low-lying areas. Volatilization can also be reduced by applying liquid or solid manures when air temperatures are cold (< 40°F). Reducing nitrogen volatilization losses and holding that nitrogen in the soil is especially important during times with high fertilizer prices and short supply.

Utilize Hay as a Nutrient Source

With the current high nitrogen prices, livestock operations may find it worthwhile to make an economic comparison of the cost of hay versus fertilizer. Rather than using nitrogen to boost pasture yields to support summer grazing, it may pencil out that purchasing additional good quality hay to use for feed during the summer months is less expensive. Additionally, like manure, hay can serve as another valuable source of nutrients for plants and can be used to offset fertilizer expenses. When you bring hay or other supplemental feed onto your farm, you are not only buying feed but also a source of nutrients at the same time. At current prices, a ton of hay can provide up to $90 or more in nutrient value alone. If spread strategically, those nutrients can provide fertilizer value to offset the cost of the hay. This can be accomplished by feeding hay on pasture, particularly on pastures with low soil fertility, and by moving hay rings, unrolling hay bales, or using bale grazing to spread fecal and hay nutrients across pastures.

Things to Watch For

As you reduce the amount of added nutrients on your fields, keep an eye on your soil test results and be aware of potential issues that may arise. Be sure to maintain adequate sulfur concentrations; sulfur is an essential nutrient for protein formation and less atmospheric sulfur is being deposited through rainfall events. Another potential issue to watch for is zinc deficiencies; fields with very high phosphorus often have zinc deficiencies caused by phosphorus binding up zinc. Lastly, be skeptical of “too good to be true” fertilizer products and enhancers, particularly ones that promise greater nutrient availability at low application rates.

When nutrient prices get to the levels we are seeing now, a little bit of planning and strategic thinking can effectively offset fertilizer purchases and go a long way in reducing the costs of production and increasing the profitability of your operation. Many of the strategies discussed here are best management practices that can and should be implemented regardless of nutrient prices, but they become especially important in times of high prices.