Andrew Kness, Agriculture Agent

University of Maryland Extension, Harford County

With the majority of full season soybeans in the region somewhere around R1-R3, growers may be considering a foliar fungicide application; however, with the current prices of soybean, is it worth the expense? That is a million dollar question and it is very difficult to answer. This article will outline a few points to consider as you try to decide if a fungicide application is worth the investment.

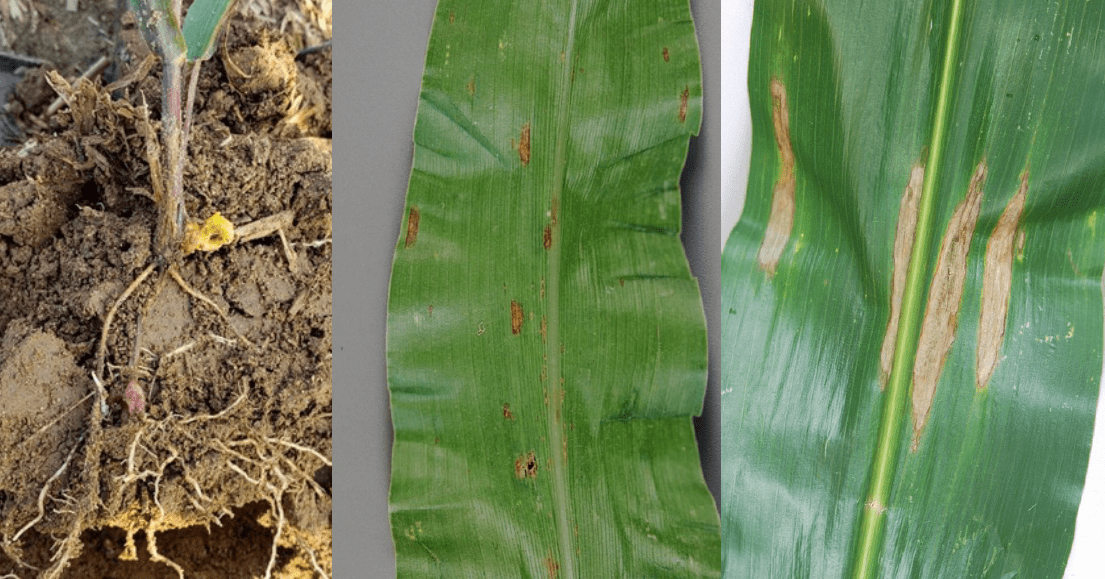

First and foremost, the purpose of a foliar fungicide application is to manage foliar diseases. This is what they are designed to do, and with the exception of where pathogens have developed resistance, they are very good at accomplishing this task. However, in order for a fungicide to achieve disease control and a yield boost, disease must be present and yield-limiting. The predominant foliar diseases of soybean in Maryland include Septoria brown spot, Cersospora leaf blight, frogeye leaf spot, and to a lesser extent, target spot and downy mildew. These diseases are all generally favored by moist, warm weather and typically do not appear in our region to any significant extent until our soybeans reach approximately reproductive phases. Historically, these foliar diseases are not typically present at high enough levels to cause a reduction on yield—but sometimes they do. It should be noted that the diseases that typically cause the major yield reductions in soybeans are stem and root diseases that infect soybeans very early in the growing season such as sudden death syndrome, charcoal rot, brown stem rot, soybean cyst and root knot nematodes, and cannot be managed with an in-season fungicide application. These diseases require a different management strategy.

If you look at the body of research on foliar fungicide effect on soybean yield, you’ll find the results to be quite variable from year-to-year. One year you may see a positive and significant yield response to a fungicide application and nothing the next year, or even at a different location within the same year. Current research on soybean indicates a positive and statistically significant yield response from a fungicide application about 30-50% of the time.

Generally, a significant yield response is achieved when foliar disease pressure is high; which goes back to the purpose of a fungicide, which is to manage disease. A positive and statistically significant yield response is more likely when disease pressure is high. The trick is trying to figure out when conditions will favor situations of higher disease pressure. If we can do that, then we can do a better job of determining when and where foliar fungicides are needed. To do this, take into account the foundation principal of plant pathology; the disease triangle.

Like any triangle, the disease triangle has three legs, which are a visual representation of the three criteria that must all be present, at the same time, in order for a disease to occur. They are: 1) a susceptible host, 2) a virulent pathogen, and 3) a conducive environment for the pathogen. If all three are present at the same time, disease will occur and this is when fungicides are a valuable tool in our toolbox. Assessing your risk in each one of these three categories can help you determine if a fungicide application is necessary. Here are some considerations for each.

Susceptible Host

Know your varieties and check the disease resistance ratings. Host resistance will significantly decrease, and in some cases completely eliminate, your risk for developing that particular disease. If you are growing susceptible varieties then you will have an increased likelihood of developing disease.

Virulent Pathogen

In the case of the major foliar diseases of soybean in Maryland, a virulent pathogen is always present. These pathogens persist on residue, waiting for a susceptible host and conducive environment to sporulate, infect, and grow.

Conducive Environment

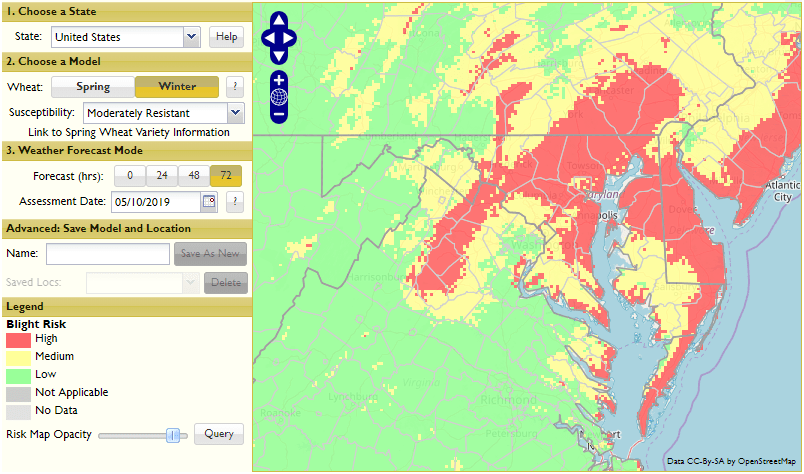

This is the most difficult leg of the disease triangle to determine and the reason why fungicide applications can be “hit or miss.” Each pathogen requires slightly different conditions for which it can grow; but in general, research indicates that temperatures within the range of 75-86°F; coupled with accumulated rainfall greater than 0.5 inches in 5 days or 1.0 inch in 10 days; or 3 days with 10+ hours of relative humidity at or above 95%, favor the development of the major foliar diseases of soybean. If these temperature and moisture conditions are met, your risk of developing foliar diseases increases.

However, as you might imagine, predicting these conditions is very difficult and the micro-climate within the soybean field itself can vary greatly from conditions outside the field (i.e. where a weather station may be located). Factors that can influence the micro-climate within a field that favor higher humidity and thus greater disease potential include: narrow row spacing that restricts airflow, higher plant populations, taller/larger plants, hedgerows, wood lines and topography that restrict airflow, fields that are prone to frequent and prolonged periods of dew or fog (for example, fields near streams/rivers), and overhead irrigation.

As a general rule, warm temperatures coupled with moisture around the time of flowering through pod development will favor disease development that could significantly reduce soybean yield.

An additional consideration is economics. If the application costs you $15 per acre, then you will need at least 1.76 bushel increase to pay for that application if your sale price is $8.50 per bushel. This is certainly attainable if disease pressure is high, but if it turns hot and dry, you would be out $15 per acre.

Also consider fungicide resistance when determining a fungicide application. From a resistance-management standpoint, it is better to only use fungicides when the probability of developing disease is likely. Indiscriminately spraying fungicides when not needed exposes the pathogens to the active ingredients and pushes fungal populations towards resistance, even if disease pressure is low. Also, cutting fungicide rates accelerates resistance. It is also important to rotate modes of action to slow the pace of fungicide resistance. Fungi can quickly develop resistance to fungicides; for example, there are several populations of Cercospora sojina, the causal agent of frogeye leaf spot, that are already resistant to Qoi fungicides (such as Quadris, Aproach, Headline, etc.).

Determining if a foliar fungicide application will provide a yield bump is difficult, but taking into consideration the above points as it relates to the disease triangle can help. For more information regarding which fungicides to use for which disease, consult this table.