Andrew Kness, Agriculture Extension Educator

University of Maryland Extension, Harford County

akness@umd.edu

If you grew wheat this year, chances are you don’t have to look too hard to find head scab/Fusarium head blight (FHB). The excessive rainfall, humidity, and warm temperatures that we had around wheat flowering provided the perfect habitat for Fusarium graminearum, the causal agent of FHB, to thrive. If you have FHB, you have few options to manage it at this point in the season as you read in Bob’s article above; but what can you do in 2019 to better your odds (besides hope for little rain during flowering)?

To understand your options you need to understand the lifecycle and biology of F. graminearum. The pathogen survives on residue, particularly that of wheat, barley, and corn and will persist through the winter on this material. During periods of wet, humid, and warm temperatures in the spring, the fungus will produce spores. If wheat or barley is growing in the field, the spores are splashed up onto the heads via rain or irrigation, or carried by the wind. If the wheat or barley is flowering, the spore can germinate and infect the plant through the flower; it cannot get into the plant any other way. This is why we recommend fungicide application at flowering. Once the pathogen infects the wheat, it grows within the spikelet, bleaching it in the process (Figure 1) and infects the developing grain, causing shriveled, light weight, discolored kernels called tombstones. Infected grain may contain deoxynivalenol (DON) vomitoxin. FHB not only reduces yield, but has the potential to contaminate your grain with DON.

With that in mind, here are some tips for managing FHB in 2019:

- Know your variety! If you plan to grow and market quality grain, then you need to know your varieties. Unlike barley, wheat does have some resistance to FHB, although it is not complete resistance. Some varities are more resistant than others, so my suggestion is to grow a variety that has the best resistance and yield potential. Consult with your seed rep and utilize the data from our wheat variety trials. A collaborative project between the University of Maryland and University of Delaware screens wheat varieties for resistance to FHB. The data can be found here, or call your Extension Office for a copy.

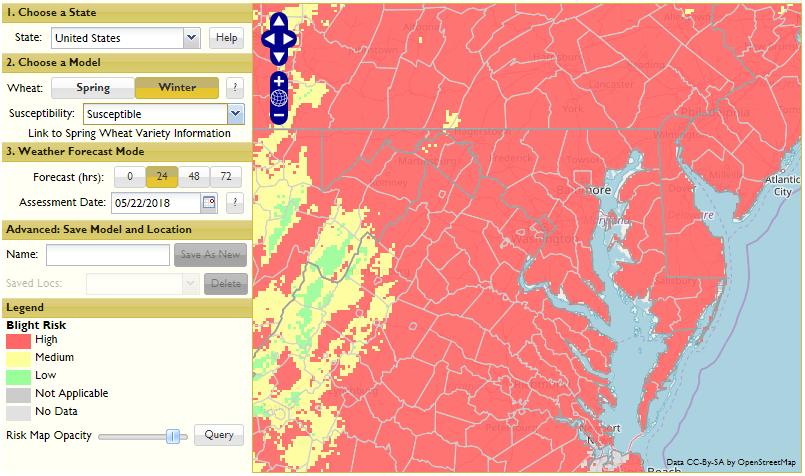

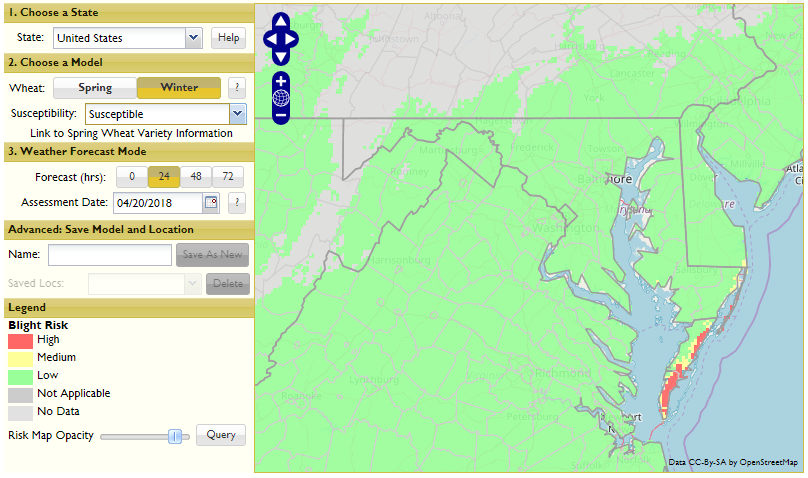

- Use a fungicide at flowering. Unless we have an exceptionally dry spring, you’ll likely need a fungicide application to protect against FHB. Use the Scab Risk Assessment Tool to help assess your risk. Time your application at the start of flowering (Feekes 10.5.1) and up to 5 days thereafter. Triazole fungicides work best, particularly Caramba (metconazole), Proline (prothioconazole), and Prosaro (prothioconazole + tebuconazole). Do not use strobilurin fungicides! See my article in the April issue for more information on fungicide strategies.

- New for the 2019 growing season will be a new product from Syngenta, called Miravis Ace (adepidyn). This will be a new mode of action fungicide (SDHI) to be used on FHB, and should help us with managing resistance by rotating it with the Triazoles. Preliminary University testing shows that Miravis Ace does well against FHB; however, claims of a wider application window seems questionable at this point, so application timing will still be critical.

- Select your best fields. Since F. graminearum can survive on small grain and corn residue, planting wheat or barley behind soybeans is better than following corn. F. graminearum doesn’t survive well on soybean residue. If you are following corn, consider a light tillage pass with a vertical till tool to size residue. This will accelerate residue decomposition, killing some of the surviving F. graminearum.

It is important to utilize as many management strategies as possible for FHB. Host resistance can only provide about 50% FHB suppression in wheat (and 0% in barley), and fungicides can only provide 50% suppression at best. Growers must use a combination of variety selection, fungicides, and cultural practices to achieve a high quality wheat or barley crop.