Amanda Grev, Pasture & Forage Specialist

University of Maryland Extension

Last month we discussed strategies for assessing pasture stands and some initial considerations when beginning to think about pasture renovations. Now that August has arrived, if you have decided to proceed with some form of pasture renovation this fall it will soon be time for planting. Regardless of the extent of your renovation, there are several steps you should follow to make sure the seeding process goes smoothly. Below is an overview of the key steps necessary for optimum forage establishment.

Step 1: Correct Soil Fertility

Poor soil fertility is one of the most common causes of poor stand establishment and also poor stand persistence over time. Acidic conditions (low soil pH) will reduce nutrient availability and impair root growth and development, and essential nutrients like phosphorus are critical for proper seedling development. Because of these effects on plant nutrient availability and utilization, ensuring adequate soil pH and fertility is essential for optimum stand establishment and to obtain persistent, high-yielding stands long term. Soil fertility testing should be done prior to renovation so that lime and fertilizer can be applied according to soil test recommendations.

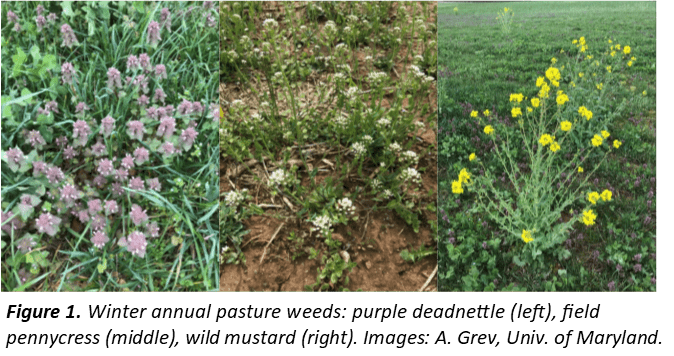

Step 2: Control Weeds

Weeds compete with desirable forages for light, nutrients, moisture, and space and can shade out or outcompete new seedlings. For best results, ensure weeds are controlled prior to seeding. Remember that while herbicides can be a useful tool for weed management, they are not the only option for weed control. An integrated approach that combines various cultural, mechanical, and chemical control practices will be the most successful.

Step 3: Select Adapted Species

Not all forages will perform equally on different sites, so be sure to select forages that are well suited for your soil and site characteristics. This includes variables such as soil type, drainage, moisture holding capacity, pH, fertility, and topography. For example, species such as orchardgrass or alfalfa require a higher level of fertility and will not thrive in systems with low soil pH or poor soil fertility. Be sure to select forage species that will match your intended use (hay vs. pasture, perennial vs. annual, time of year, management system) and livestock requirements based on species, age, and life stage.

Step 4: Inoculate Legume Seeds

If you plan to incorporate a legume as part of your forage mix, be sure the seed is properly inoculated with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Some legume seeds come pre-inoculated, which saves time and helps to ensure inoculation. If not, be sure to select the appropriate inoculant strain depending on the legume species and inoculate the seed with fresh inoculant prior to seeding using an effective adhesive material to hold the inoculant on the seed. Inoculants are living organisms and will only work if the bacteria are alive when applied, so be sure to use proper storage and handling and check expiration dates.

Step 5: Graze and/or Clip Close

Grazing or clipping a pasture close to ground level prior to seeding will help eliminate residue and assist in suppressing competition from existing vegetation, giving new seedlings an opportunity to grow. If using livestock to accomplish this via grazing, be mindful of the potential effects this may have on animal performance, including the consumption of lower quality forage and/or the potential for increased parasite loads as animals graze below the usual minimum height recommendation.

Step 6: Prepare a Proper Seedbed

This step will vary slightly depending on the use of tilled vs. no-till seedings. If using tillage, be sure the seedbed is soft yet firm following tillage. An underworked seedbed will have too much surface residue and will be too rough for good seed placement, while an overworked seedbed will be too fluffy and fine and will dry out quickly. A good rule of thumb is that your boot tracks should be around ¼ inch deep. For no-till seedings, it is especially important to suppress the existing stand and reduce residue prior to planting. In addition to close grazing and/or clipping, the existing stand can be suppressed using a nonselective herbicide.

Step 7: Seed at the Proper Depth

Seeding too deep is one of the most common causes behind establishment failures. Be sure the seed drill is calibrated appropriately so that seed is placed at the proper depth. Take into account your soil type, texture, and moisture conditions; in general, seed should be placed slightly shallower in a heavier soil with a higher moisture content and slightly deeper in a lighter soil with lower moisture content. For most cool-season forages, the ideal seeding depth is ¼ to ½ inch, but seed characteristics vary so be sure to determine the optimum depth and adjust accordingly prior to planting. The key is to provide good seed to soil contact without placing the seed too deep.

Step 8: Seed at the Proper Time

Cool-season forages can be seeded in either the spring or late summer. Advantages of late summer seedings generally include reduced weed competition and cooler weather conditions during establishment. The ideal time will vary depending on your location and weather conditions but in general, the optimum time for late summer seeding in Maryland occurs from mid-August through mid-September.

Step 9: Seed at the Proper Rate

Similar to seed depth, calibration is essential to achieve a proper seeding rate. Seeding rates will vary based on forage species selection, be sure to follow recommendations when making seeding rate decisions. Pasture seeding rates are typically higher than hay seeding rates to provide a denser sod for grazing. Seeding rates can be adjusted slightly based on conditions at the time of seeding. If conditions are optimum, seed at the lower end of the recommended range. If conditions are poor, seed at the higher end of the recommended range.

Step 10: Manage New Seedings During Establishment

New seedings are especially sensitive during their establishment year. To maximize success, delay grazing on newly seeded areas until sufficient root systems have been developed to prevent livestock from uprooting newly established plants when grazed. Avoid grazing new stands during extremely wet periods, be very careful not to overgraze, and continue to scout for weeds or other potential issues that can impair establishment.