Great Minds

Eleanor Roosevelt encouraged people to hold elevated conversations. She once said that “great minds discuss ideas; average minds discuss events; and small minds discuss people.” I have not heard a more elevated conversation than the week-long discussion between the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu documented in vivid detail in The Book of Joy by Douglas Abrams.

The Dalai Lama received Archbishop Tutu in the Himalayan town where he resides in exile—Dharamsala, India. Although casually described as merely an opportunity for the two friends to celebrate the Dalai Lama’s 80th birthday, the actual purpose of the meeting was to have a week-long documented conversation with the intention of writing this important book and answering universally-relevant and all-important questions.

Diplomacy

Bringing these two celebrated men together has been a diplomatic challenge. The Archbishop was diagnosed with prostate cancer and has been battling medical difficulties for many years, reducing his ability to freely travel. When the Dalai Lama attempted to visit the Archbishop in South Africa to celebrate the Archbishop’s 80th birthday, he was not granted a visa by the South African government. There is strong evidence that the refusal was because of the South African government’s fear of upsetting China—a critical investor and consumer of South African minerals. Given these medical and diplomatic limitations, the Archbishop’s visit to Dharamsala in April 2015 to write this book became a bittersweet reunion between the two Nobel Laureates and best friends.

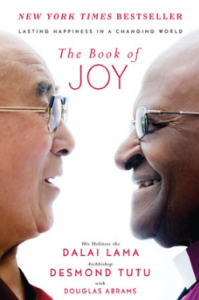

Archbishop Tutu teaching the Dalai Lama how to boogie; The Book of Joy, Back Cover

Archbishop Tutu teaching the Dalai Lama how to boogie; The Book of Joy, Back Cover

Spiritual Contributions

Both the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Tutu have led difficult lives and faced great oppression. The Dalai Lama, who is the 14th leader of the Tibetan people, was forced to flee in 1959 due to China’s assertion of control over Tibet. The Dalai Lama escaped in the middle of the night from the historic Potola Palace dressed as a palace guard and fled to India, where he has since lived as a refugee along with some of the Tibetan people.

Desmond Tutu, a South African Anglican Archbishop, rose to worldwide fame as an opponent of apartheid and faced death threats and severe hostility in his efforts to create a just and equal South Africa. In post-Apartheid South Africa, Tutu has campaigned to fight HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, poverty, racism, sexism, and homophobia.

Tutu’s most renown spiritual contribution to social justice may be as the patron of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission—a restorative, justice body in which witnesses testified about human rights violations, while perpetrators of violence also gave testimony and requested amnesty. Though by no means perfect, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is internationally recognized as an impressive and meaningful application of the spiritual concepts of forgiveness and healing to criminal justice and war crimes proceedings.

The Dalai Lama playfully greeting his recently arrived friend at Dharamsala Airport; The Book of Joy; Introduction

The Dalai Lama playfully greeting his recently arrived friend at Dharamsala Airport; The Book of Joy; Introduction

What is joy?

During the week that the two spiritual leaders met, they attempted to answer one of the most elusive questions presented to humanity: “What is true joy and how do we achieve it?” They discussed numerous universally-relevant concepts including anxiety, frustration, envy, humor, forgiveness, and gratitude with precision and clarity. I found their conversation on the purpose of life to be the most interesting topic covered. Despite the structural difference of their worldview on this topic given the differences in their religions, the Dalai Lama and Archbishop impressively came to the same essential conclusion. They agreed that the essential purpose of life is to improve our virtues and explained how all of the major faiths teach this same concept.

Our goal on this planet is to exit being better people than we were coming in despite of—indeed because of—the trials, injustices, and hardships presented by life. They compared our response to the hardships of life to something as mundane as working out at the gym—by actively reflecting on our spiritual state and responding to predicaments in a way that is spiritually mindful, we can become spiritually stronger and more resilient and therefore have the capacity to create meaningful, positive change in the world. The two leaders’ conclusion about the purpose of life reminded me of a quote from a Bahá’í leader, Shoghi Effendi: “The troubles of the world pass, and what we have left is what we have made of our souls.”

About the Author:

Sharath Patil is a fellow on economics and trade at the University of Maryland’s Baha’i Chair for World Peace. He is a second-year law student at the University of Oregon School of Law and has a bachelor of science in supply chain management from Arizona State University. He has significant academic and professional experience in international trade, global logistics, and commercial diplomacy. Patil is passionate about the ability of sustainable and resilient global supply chains to serve as a force for development and a bridge for peace.

Sharath Patil is a fellow on economics and trade at the University of Maryland’s Baha’i Chair for World Peace. He is a second-year law student at the University of Oregon School of Law and has a bachelor of science in supply chain management from Arizona State University. He has significant academic and professional experience in international trade, global logistics, and commercial diplomacy. Patil is passionate about the ability of sustainable and resilient global supply chains to serve as a force for development and a bridge for peace.