It’s hard to remember that our lives are such a short time. It’s hard to remember when it takes such a long time.” – Isaac Brock

I first read Viktor E. Frankel’s Man’s Search for Meaning a few years ago in college. My professor had assigned the book for a seminar and prefaced our study of Frankl’s work by telling us that this book is one to revisit every couple of years. As a 19-year-old, I had found this book impactful. So, I decided to revisit this book as a graduate student.

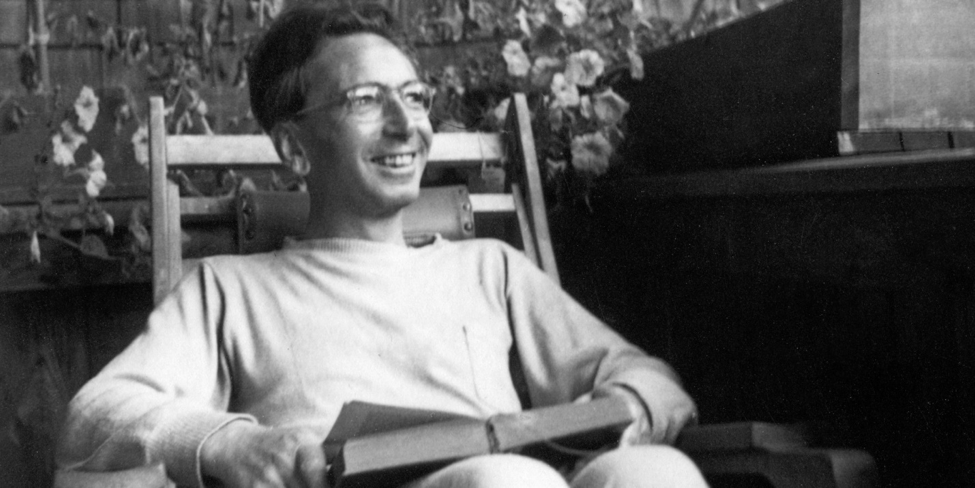

Viktor Frankl was an Austrian, Jewish psychiatrist who pioneered logotherapy, a form of existential analysis focused on finding meaning in life.

At the eve of World War II, Frankl was offered a visa to move to the United States by the U.S. Embassy in Vienna, but he turned down this opportunity in order to care for his parents.

In 1944, Frankl was transported to the Auschwitz concentration camp (and other successive camps), where he endured a harrowing and unspeakable experience. In 1945, Frankl’s camp was liberated by American soldiers, and Frankl returned to his native Vienna, where he engaged in groundbreaking research on logotherapy and gained international fame for his teachings on finding meaning in life.

Victor Frankl Photograph from the Huffington Post

Man’s Search for Meaning is a two-part account: the first half discusses Frankl’s experience at the concentration camps, and the second half is comprised of universally applicable lessons gleaned from Frank’s struggle.

The book is an absolute treasure. There are few such explicit, overwhelming, and absolutely honest accounts of life in the concentration camps. Frankl’s description of the emotional, spiritual, and social dynamics of his experience, as well as that of other prisoners, is tremendously humbling and beautiful.

“The thought of suicide,” he recalls, “was entertained by nearly everyone, if only for a brief time. It was born of the hopelessness of the situation, the constant danger of death looming over us daily and hourly, and the closeness of the deaths suffered by many of the others.”[1]

Meanwhile, in the second half, Frankl successfully does the impossible—after sharing his account of life in the concentration camp, he shares with posterity how we can learn from his experience. The notion, initially, I found extremely strange. My life is not remotely like Frankl’s experience, so I was hesitant to even think about how the horrors of Frankl’s experience could relate to my own life.

However, Frankl’s lesson is perhaps the single most important lesson of life—a concept described in all of the world’s great religions. Frankl explained, in such simple language, the importance of finding and cultivating meaning and purpose in our lives—and how doing so can provide each of us with the strength to survive—regardless of the severity of our trials and hardships.

Auschwitz Concentration Camp Photograph from the Holocaust Research Project

Frankl implicitly asks, throughout the book, what we have in our own life if we have nothing of the world. Who are we if we do not have our degrees, our family, our home, our name? If some or all of this is taken from us, what defines us? What keeps us going? And why?

In Frankl’s experience at Auchwitz and Dachau, he saw two types of men. The first type were those who one day came to the conclusion that waking up every day just to submit to hard labor and scrape by when death was so certain meant that life was useless and they might as well give up.

As Frankl put it, “A man who could not see the end of his ‘provisional existence’ was not able to aim at an ultimate goal in life. He ceased living for the future, in contrast to a man in normal life.”[2] A second type of individual insisted on striving despite all the obscene and heartless challenges, the utter, absolute hopelessness of it all.

Frankl said that the distinguishing factor was one’s ability to find meaning, and teaches everyone that our ability to find and pursue meaning will strengthen us in any trial, big or small.

Perhaps most inspiring of all were some truly kindred souls that Frankl came across in the concentration camp: “We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

These brave men and women give each of us little excuse to ignore the needs of our communities, and they are a standing example of how even when we have nothing, we can be generous.

It is what we make of what we have, not what we are given, that separates one man from another.

– Nelson Mandela

[1] Victor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, 18.

[2] Victor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, 70.

About the Author:

Sharath Patil is a fellow on economics and trade at the University of Maryland’s Baha’i Chair for World Peace. He is a second-year law student at the University of Oregon School of Law and has a bachelor of science in supply chain management from Arizona State University. He has significant academic and professional experience in international trade, global logistics, and commercial diplomacy. Patil is passionate about the ability of sustainable and resilient global supply chains to serve as a force for development and a bridge for peace.

Sharath Patil is a fellow on economics and trade at the University of Maryland’s Baha’i Chair for World Peace. He is a second-year law student at the University of Oregon School of Law and has a bachelor of science in supply chain management from Arizona State University. He has significant academic and professional experience in international trade, global logistics, and commercial diplomacy. Patil is passionate about the ability of sustainable and resilient global supply chains to serve as a force for development and a bridge for peace.