This is a blog post written by Sharath Patil examining the policies of austerity.

Introduction

The 20th century British philosopher, Bertrand Russell, famously wrote, “The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people so full of doubt.”[i] This assessment is especially accurate in the realm of international fiscal policy. The global economy is vastly complex with so many stakeholders and moving parts that it is next to impossible to clearly identify the benefits and harms of domestic fiscal policies and bilateral and multilateral economic agreements. This being the case, forecasts, predictions, and even retrospective assessments are essentially speculation and there is a vacuum for quantitatively-driven and rational solutions. The result is that the vacuum is filled by ideologies and even hunches. Like international trade policy and international security policy, it is hard to know what the “right” thing to do is in international fiscal policy, and hindsight might not even be helpful. A 2016 article in The Economist put it well when it said, “At the heart of the problem is that it is impossible to isolate one part of economic policy and run a ‘control’ as in a proper scientific experiment.”[ii]

Overview of Austerity

There are a few commonly cited definitions of ‘austerity,’ namely: (1) a form of voluntary deflation in which the economy adjusts through the reduction of wages, prices and public spending to restore competitiveness, which is (supposedly) best achieved by cutting the state’s budget, debts, and deficits,[iii] (2) a situation in which there is not much money and it is spent only on things that are necessary,[iv] and (3) difficult economic conditions created by government measures to reduce public expenditure. Id at 3. On its face, these definitions are highly appealing to me. After all, everyone – even sovereigns – must live within their means, and resource limitations are a reality. During hard times, families and firms alike will tighten their purse strings. Should governments not do the same?

Austerity – and fiscal discipline, generally – are one of two overarching means for economic recovery at the nation-state level. The other commonly regarded strategy involves doing the opposite – stimulating growth by surging public spending during hard times. While the response to the Great Depression involves the latter strategy, more recent economic downturns including the 2008 recession have led more often to the austerity strategy in many economies including Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Iceland.

Intuitively, austerity makes sense to me. At the microeconomic level, market actors are rewarded for fiscal discipline. Families, firms, banks, and institutions alike are rewarded for remaining solvent and being responsible – incentives to stay solvent include the perpetuity of the economic entity, keeping credit ratings high, and having the opportunity to invest profits to make even more money. Similarly, the idea of austerity on a national scale appeals to me, too. After all, something has got to give if a sovereign systematically overspends and borrows to the point of insolvency. Nation-states do not exist in a vacuum – they exist in a grand community of other nation-states and international economic actors that are invested in the economic well-being of every nation-state. Nation-states, therefore, have a responsibility both to their citizens and the global community to be financially responsible.

It is curious to me how fiscal discipline can be achieved by raising taxes or cutting spending, but macroeconomists often rely on cutting spending as the far more efficient method of reducing debt. In particular, it is interesting how these two methods fall somewhat along party lines in the United States, with Democrats generally being in favor of increased public spending while Republicans are generally in favor of decreased taxes. I am unsure where the architects of these externally-imposed, internationally-involved austerity plans – like the one in Greece – fall in our American conception of a political spectrum.

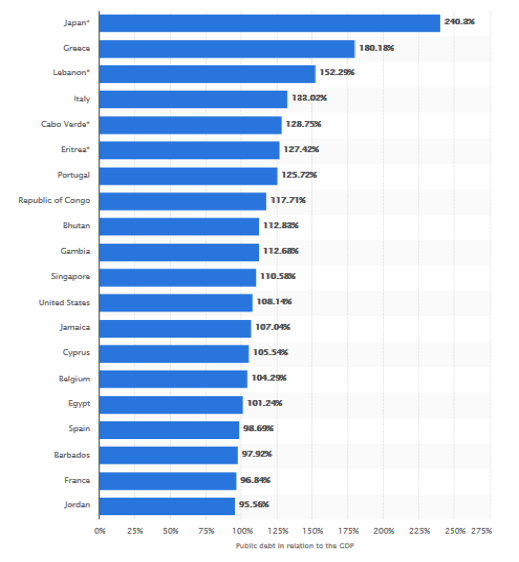

Twenty Highest Debt-to-GDP Ratios (2017)[v]

Figure 1: Although highly developed and developing countries alike suffer from high debt-to-GDP ratios, the reality and consequences are different depending on development levels

Figure 1: Although highly developed and developing countries alike suffer from high debt-to-GDP ratios, the reality and consequences are different depending on development levels

Although the arguments for fiscal discipline and austerity are intuitive, commonsensical, and compelling, it is a mistake to regard sovereigns as economic entities subject to the same principles and standards of all microeconomic actors. After all, the raison d’être of a nation-state is distinct from that of an individual, family or firm. Although all of the above seek to exist in perpetuity, the primary function of a nation-state is distinct and calls for a higher moral obligation (especially when compared to a firm). Nation-states do not exist to be fiscally disciplined, and certainly do not exist to make a profit. Therefore, judging a nation-state by the same fiscal standards applied to non-state actors is problematic.

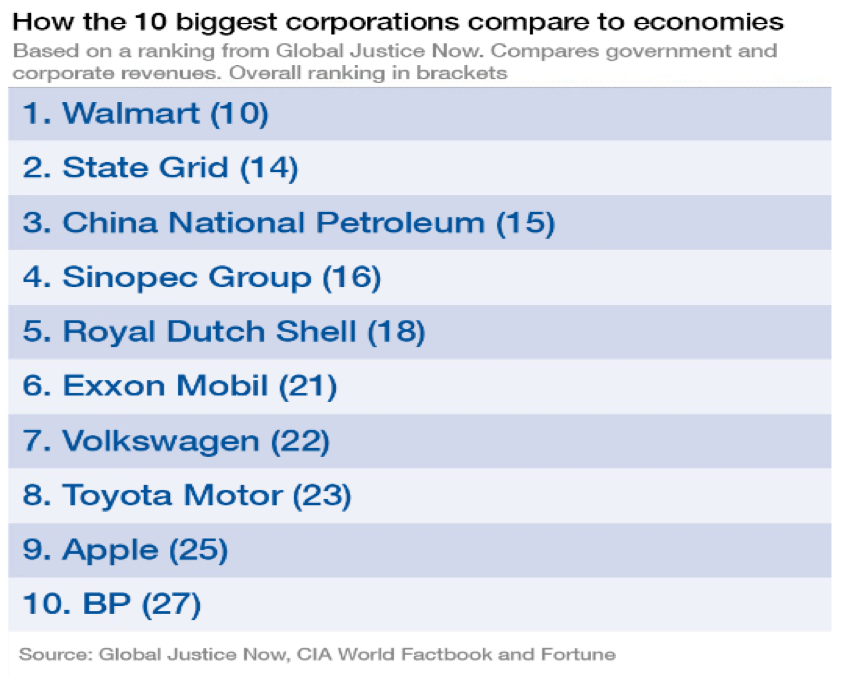

Figure 2: Multi-national corporations are not necessarily smaller than nation-states in economic power; these large corporations could each be one of the large economies of the world[vi]

Figure 2: Multi-national corporations are not necessarily smaller than nation-states in economic power; these large corporations could each be one of the large economies of the world[vi]

Systematic Flaws of Austerity

Bartl and Karavias identify numerous systemic flaws with austerity – particularly as applied to Greece. These include: 1) the fallacy of composition problem (not every nation-state can austere at once), 2) the fact that being part of a monetary union makes currency devaluation not possible, and 3) austerity centers around fiscally reforming states and not banks. Perhaps the most interesting criticism offered by Bartl and Karavias was that the peripheral PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain) of the European Union may be bearing the debt burden on behalf of the entire economic bloc that paves the way for the surpluses and growth enjoyed by the core (Germany, Netherlands, France, etc.). This argument is fascinating to me because of how interconnected and intertwined economic interests are in the EU. It is an impossible task to assign blame within an economic bloc. We do not go around assigning such blame within the United States even though we know that Texas, California and New York systematically prop-up states like Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana (see Table 1). When nation-states come together to form an economic bloc, perhaps all the nation-states should reframe their roles and responsibilities and not be so petty about having to pay off, monitor or restructure the debts of the peripheral countries. After all, the economic benefits enjoyed by the EU as a whole (including the core states) because of free trade, free movement, and free investment must pale in comparison to the debt crisis. If it did not, the peripheral countries would not have applied for EU ascension and the core countries would not have granted accession.

Money Received from Federal Gov’t for Every $1 Paid in Federal Taxes (2005)[vii]

| State | Outlay to Tax Ratio

|

|

| New Mexico | $2.03 | |

| Mississippi | $2.02 | |

| Alaska | $1.84 | |

| Louisiana | $1.78 | |

| West Virginia | $1.76 | |

| North Dakota | $1.68 | |

| Alabama | $1.66 | |

| South Dakota | $1.53 | |

| Kentucky | $1.51 | |

| Virginia | $1.51 | |

| Montana | $1.47 | |

| Hawaii | $1.44 | |

| Maine | $1.41 | |

| Arkansas | $1.41 | |

| Oklahoma | $1.36 | |

| South Carolina | $1.35 | |

| Missouri | $1.32 | |

| Maryland | $1.30 | |

| Tennessee | $1.27 | |

| Idaho | $1.21 | |

| Arizona | $1.19 | |

| Kansas | $1.12 | |

| Wyoming | $1.11 | |

| Iowa | $1.10 | |

| Nebraska | $1.10 | |

| Vermont | $1.08 | |

| North Carolina | $1.08 | |

| Pennsylvania | $1.07 | |

| Utah | $1.07 | |

| Indiana | $1.05 | |

| Ohio | $1.05 | |

| Georgia | $1.01 | |

| Rhode Island | $1.00 | |

| Florida | $0.97 | |

| Texas | $0.94 | |

| Oregon | $0.93 | |

| Michigan | $0.92 | |

| Washington | $0.88 | |

| Wisconsin | $0.86 | |

| Massachusetts | $0.82 | |

| Colorado | $0.81 | |

| New York | $0.79 | |

| California | $0.78 | |

| Delaware | $0.77 | |

| Illinois | $0.75 | |

| Minnesota | $0.72 | |

| New Hampshire | $0.71 | |

| Connecticut | $0.69 | |

| Nevada | $0.65 | |

| New Jersey | $0.61 | |

| District of Columbia | $5.55 |

Table 1: It is interesting how there is such strong, systemic disparity in the distribution of federal funding. This disparity is not a source of significant consternation. Nevertheless, there is sufficient pressure on states themselves to be solvent. I am curious whether and how this federal model can be applied to international economic blocs like the EU. Alternatively, perhaps it is not possible because it is a cultural issue. Perhaps in the U.S., California, Texas, and Alabama have a lot more in common than cultural divisions. Meanwhile, the added factors of nationalism, linguistic differences, and historical differences in Europe may make this model difficult to apply there.

In addition to the systemic flaws of austerity identified by Bartl and Karavias, historical, national, and cultural prejudices may play a role in the forced humiliation and shame of Greece in the Eurozone crisis. Stereotypes of southern European laziness, a hierarchy among European nation-states, and unreconciled tensions and histories may all contribute to the widespread condescension so many EU member-states have towards the Greeks. Essentially, the Eurozone crisis may not only be characterized by the accounting figures, but also unresolved cultural tensions.

Hours Worked Annually (2013)[viii]

Figure 3: Hours worked by Greeks is much higher than many other developed countries. The stereotype of Greek laziness may be entirely unfounded

Austerity & Human Rights

Margot Salomon from the London School of Economics makes a compelling argument that austerity is a human rights problem just as much as it is an economic one. In very strong language, Salomon argues that there is a “categorical disregard for the human rights of the people of Greece by international creditors.”[ix] She goes on to provide examples of austerity harms that are intrinsically human rights violations – including 1) the hallowing-out of the national democracy by requiring Greece to consult and agree with institutions on all relevant draft legislation before submitting to Parliament, 2) the failure of international creditors to undertake human rights impact assessments, and 3) the disparate impact of austerity on the poor and the resulting difficulty of the poor to have access to essential government services. Id. I am torn about this argument – a part of me is highly sympathetic while another part of me is critical of Salomon’s argument.

As a counter-argument to Salomon’s claim, I would point out that resource limitations are a reality of governance. If a government systematically overspends, routinely borrows to cover the widening gap between tax revenues and public expenses, and can only remain solvent through an emergency, external bailout, then perhaps a strict externally-imposed austerity measure is valid despite the human rights violations and the disparate harm to the poor. After all, one could argue, it was the responsibility of the Greek government not to be in such a situation in the first place, and a failure to be independently responsible resulted in an external bailout and externally-dictated austerity program.

That said, I am not sure I am confident with this counter-argument. The politics of wealth inequality are complex, as are the politics of austerity. The fact that in this situation, the politics of wealth inequality are embedded in the politics of austerity and fiscal discipline makes it exceedingly difficult to figure out the merit of these human rights claims. It seems entirely possible that the irresponsibility I described on the part of the Greeks in the preceding paragraph was not the fault of the Greek proletariat at all, but rather the irresponsibility of the wealthy and politically powerful. Similar to the 2008 recession in the United States in which the irresponsibility and avarice of the wealthiest of Americans led to difficulties for the masses of this country’s poor, the poor of Greece may be unfairly facing the consequences of their wealthier counterparts’ conduct.

Finally, Salomon’s conflation of sovereignty and human rights is interesting to me. It is certainly true that the right to self-determined governance is a human right. However, it is also true that the global super-network of equity and debt knows no boundaries and we are all inextricably bound. Economic difficulties anywhere affect us all and it is in everyone’s interest to have a thriving global economy. In such a reality, I think that the sovereignty arguments embedded within the human rights arguments may be entirely obsolete. When Greece is irresponsible and risks being insolvent, it does not only harm itself but the world. The Greek government has a responsibility not only to the Greek people but also to all of the stakeholders worldwide eager to see Greece succeed. Although it is troubling that the EU and the IMF have so much influence in Greek democratic processes, this entire intervention was meant as a failsafe in the first place. I am unsure if it is possible to preserve Greek sovereignty and democratic processes in their entirety while also ensuring there is sufficient pressure on Greece to rectify itself given that it intends very much to be a part of the EU and the liberal world order.

References

[i] “Bertrand Russell: ‘The Problem with the World Is That Fools & Fanatics Are So Certain of Themselves’” (Mar. 26, 3:04 PM), http://www.openculture.com/2016/06/bertrand-russell-the-problem-with-the-world-is-that-fools-fanatics-are-so-certain-of-themselves.html.

[ii] Fiscal Policy: What is Austerity? The Economist (Jan 20, 2016, 12:29PM), https://www.economist.com/blogs/buttonwood/2015/05/fiscal-policy.

[iii] Marija Bartl & Markos Karavias, Austerity and Law in Europe: An Introduction, 2017 J. L. Soc. 1.

[iv] Fiscal Policy: What is Austerity? The Economist (Jan 20, 2016, 12:29PM), https://www.economist.com/blogs/buttonwood/2015/05/fiscal-policy.

[v] The 20 countries with the highest public debt in 2017 in relation to the gross domestic product (GDP), STATISTICA (Mar. 26, 2018, 4:46 PM), https://www.statista.com/statistics/268177/countries-with-the-highest-public-debt/.

[vi] Joe Myers, How do the world’s biggest companies compare to the biggest economies? WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM (Mar. 27, 2018, 4:33 PM), https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/10/corporations-not-countries-dominate-the-list-of-the-world-s-biggest-economic-entities/

[vii] Federal Taxing and Spending Benefit Some States, Leave Others Paying Bill, TAX FOUNDATION (Mar. 26, 2018, 5:01 PM), https://taxfoundation.org/press-release/federal-taxing-and-spending-benefit-some-states-leave-others-paying-bill-1/

[viii] Thanasis Delisthatis, Greece’s Debt Crisis Explained in 20 Charts, GREEK REPORTER (Mar. 27, 2018, 5:45 PM), http://greece.greekreporter.com/2015/05/23/greece-debt-crisis-explained-infographics-greek/ .

[ix] Margot Salomon, Europe’s Debt to Greece (Mar. 27, 2018, 10:13 AM), https://www.ejiltalk.org/europes-debt-to-greece/#more-13533.

About the Author:

Sharath Patil is a fellow on economics and trade at the University of Maryland’s Baha’i Chair for World Peace. He is a second-year law student at the University of Oregon School of Law and has a bachelor of science in supply chain management from Arizona State University. He has significant academic and professional experience in international trade, global logistics, and commercial diplomacy. Patil is passionate about the ability of sustainable and resilient global supply chains to serve as a force for development and a bridge for peace.

Sharath Patil is a fellow on economics and trade at the University of Maryland’s Baha’i Chair for World Peace. He is a second-year law student at the University of Oregon School of Law and has a bachelor of science in supply chain management from Arizona State University. He has significant academic and professional experience in international trade, global logistics, and commercial diplomacy. Patil is passionate about the ability of sustainable and resilient global supply chains to serve as a force for development and a bridge for peace.