Sarah Potts, Dairy & Beef Specialist

University of Maryland Extension

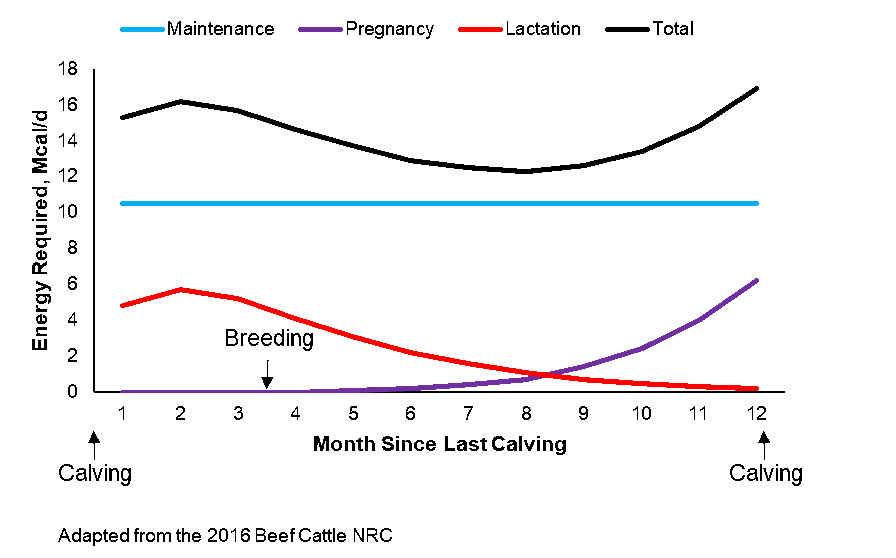

As fall progresses, spring-calving beef producers should be thinking about how they will maintain their pregnant cows throughout the winter. The nutritional requirements for gestation increase during the second and third trimesters, which coincides with colder temperatures and decreased forage availability from pasture.

Adequate Nutrition is Vital

Ensuring proper nutrition is an important component of maintaining animal productivity and efficiency. Failing to meet nutritional requirements during pregnancy can have devastating effects on future productivity of the cow. Undernourishment during pregnancy can result in reduced body condition at calving, increased rates of dystocia (calving difficulty), decreased colostrum quality and quantity, and poor lactation performance. Cows that are in less than ideal body condition at calving generally take longer to begin cycling and showing signs of estrus (heat) after calving, and are at higher risk for being open at the end of the breeding season.

Poor gestational nutrition can have indirect, but profound, effects on the survivability and performance of calves. Dystocia is associated with increased calf mortality and inadequate consumption of quality colostrum can lead to increased calf morbidity (illness) and mortality. In addition, poor milk production by the dam will prevent her calf from achieving desirable gains.

Meeting Winter Nutritional Needs

Although the nutritional needs associated with pregnancy increases during a time when feed availability is limited for spring calving herds, the good news is that there are many strategies that can be used to minimize costs. Ultimately, producers will have to choose for themselves which feeding practice that best fits their situation and goals.

Beginning in the late fall when pasture growth becomes limited, stockpiled forages can be used to feed cows. Generally, stockpiled forages can meet the nutritional needs of pregnant cows during mild to moderate temperatures as long as sufficient quantities are available. However, as winter sets in and temperatures drop, supplemental feeds may be necessary to offset the increase in maintenance energy requirements that are associated with lower temperatures. Additional protein, such as alfalfa hay or soybean meal mixes, may also be required if forage protein content becomes inadequate.

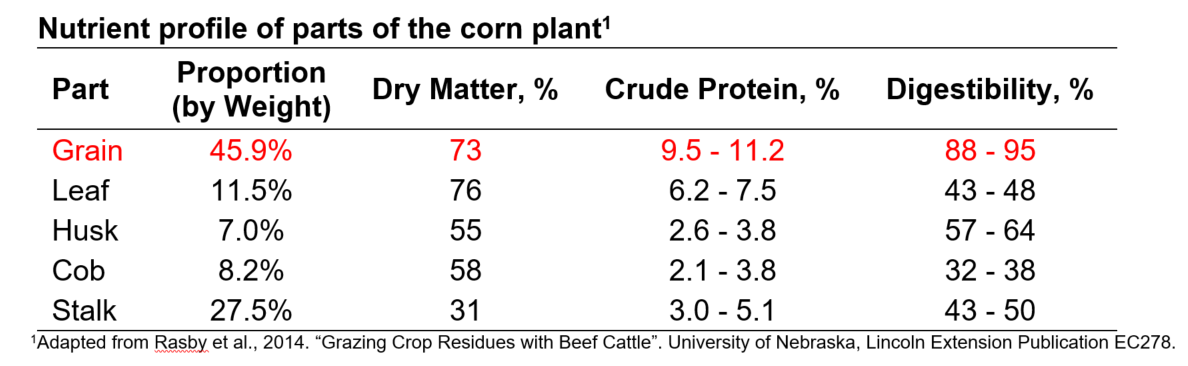

Late-fall grazing of corn residue can be used to spare stockpiled forages for later in the winter. However, this is not always a practical option for many producers since these fields are often not fenced or in proximity to a water source. An additional protein source is usually required, especially after the most nutrient dense portions of the residue (leaves and husk) have been consumed.

Many producers often elect to supplement with hay during the winter months, which can be a good option. However, it is important to know the nutrient composition of the hay to ensure sufficient protein and digestible dry matter is supplied. The amount of hay that a cow will consume depends on the quality. Low quality hay (<52% TDN) is less digestible than high quality hay, which can limit feed intake by increasing gut fill. During the last two trimesters of pregnancy, mature cows generally consume 2 to 2.5% of their body weight on a dry-matter basis. For a 1,200 lb cow, this equates to 24 to 30 lb of hay per day on a dry-matter basis, or approximately 27 to 33 lb per day on an as-fed basis. Knowing approximately how much hay cows will need is helpful in determining how much must be purchased for the season and how much will need to be fed each week.

Additional feeds, such as corn silage, may also be fed during the winter months if good quality hay and/or stockpiled forages are insufficient to meet the needs of the cow herd. However, this option may increase the cost of the winter feeding program.

Evaluation of the Winter Feeding Program

A key area to look at when evaluating the winter feeding program is body condition. Body condition (1 to 9 scale) of cows should be assessed at weaning to determine whether or not additional feed will be required throughout the winter. The ideal body condition score at calving is 5 to 6. If cows are too thin at weaning (less than a score of 5), additional feeds may be required so that they can gain the weight necessary to achieve optimal performance after calving. Conversely, if cows are too fat at weaning (greater than a score of 6), then they will not require as much feed during the winter. Assessment of body condition at this time is important to planning and allocating feeds for the winter.

Condition should also be assessed 60-90 days before calving so that additional adjustments to the feeding regime can be made if necessary. Ultimately, body condition at calving and subsequent cow and calf performance, will indicate the overall success of the winter feeding and management program.