Dr. Sarah Potts, Dairy & Beef Specialist

University of Maryland Extension

Background:

The USDA CFAP Program has allocated $16 billion in funds for direct payments to farmers to help with the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. The funds are derived from two sources: the Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) Charter Act. Funds from the CARES Act are meant to help farmers cope with price reductions incurred between mid-January and mid-April while funds from the CCC Charter Act are meant to help farmers cope with market disruptions.

Eligibility:

All producers who incurred a 5% or greater reduction in commodity prices due to the COVID-19 pandemic are eligible to apply for aid. If more than 75% of an applicant’s income is from farming, there are no gross income restrictions. However, if less than 75% of income is derived from non-farming sources, the average adjusted gross income on the applicant’s 2016, 2017, and 2018 tax returns must be less than $900,000. Participation in risk management programs, such as the Dairy Margin Coverage Program, and Small Business Administration (SBA) programs, such as the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), do not affect a producer’s eligibility for CFAP aid.

Funding Limitations:

Individual producers or farms are eligible for up to $250,000 of aid. However, if your farm business is structured as a Corporation, Limited Liability Company, Limited Partnership, etc., you may be entitled to a higher limit of up to $750,000 depending on the number of shareholders who contribute more than 400 hours of labor annually to the farm business.

Applications and Payments:

The application period begins on Tuesday, May 26th and goes through August 28th, 2020. Producers must call their local Farm Service Agency (FSA) office in order to schedule an appointment to complete the application process. Producers will receive 80% of their payment as soon as their application is completed and processed. The remaining 20% of their payment will be dispersed at a later date, as funds are available.

A payment estimate calculator and other resources will be made available at https://www.farmers.gov/cfap beginning May 26th to help farmers estimate the amount of aid they should receive.

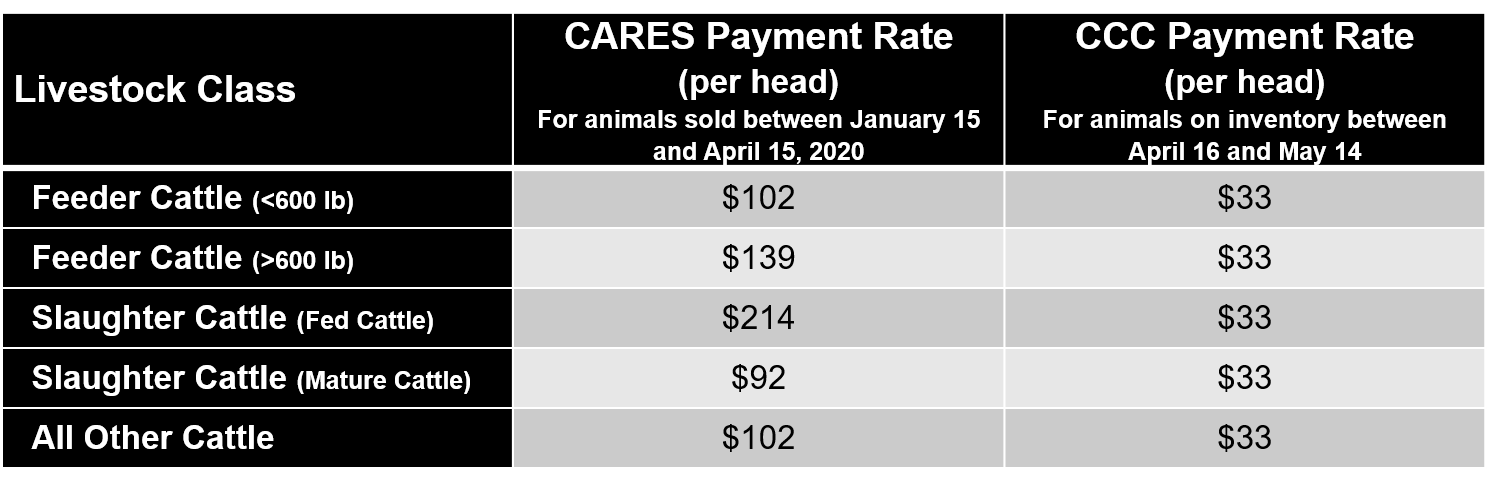

Beef producers are eligible to apply for aid based on the number of cattle marketed between January 15 and April 15, 2020 (CARES Act payments; column 1 in Table 1) and the greatest number of cattle on inventory between April 16 and May 14, 2020 (CCC Charter Act payments; column 2 in Table 1). Payment rates vary depending on the type of cattle sold or in inventory during these time periods.

Table 1. CFAP Payment Structure Based on Cattle Class.

Example:

A beef producer applies for aid as an individual. She sold a total of 3 cull cows and 20 feeder cattle (<600 lb) between January 15 and April 15. From April 16 to May 14, she managed 30 cow/calf pairs, 1 mature breeding bull, and 3 feeder cattle (>600 lb) that she intends to finish out and sell as freezer beef.

This producer should be eligible for up to $250,000 of aid because she is applying as an individual. The total maximum payment she can expect is calculated as follows:

CARES Act Funds (column 1): $2,316

- $276 for the 3 cull cows sold: $92/head × 3 head

- $2,040 for the 20 feeder calves (<600 lb) sold: $102/head × 20 head

CCC Charter Act Funds (column 2): $2,112

- $1,980 for the 30 cow/calf pairs: 30 cows + 30 calves = 60 head × $33/head

- $33 for the breeding bull: 1 bull × $33/head

- $99 for the 3 feeder cattle (>600 lb): 3 head × $33/head

This producer is expected to receive a maximum payment of $4,428. The initial payment this producer can expect to receive is $3,542.40 (80% of $4,428).

For additional information, visit https://www.farmers.gov/cfap or contact your local FSA office.