Glorious Revolutions?

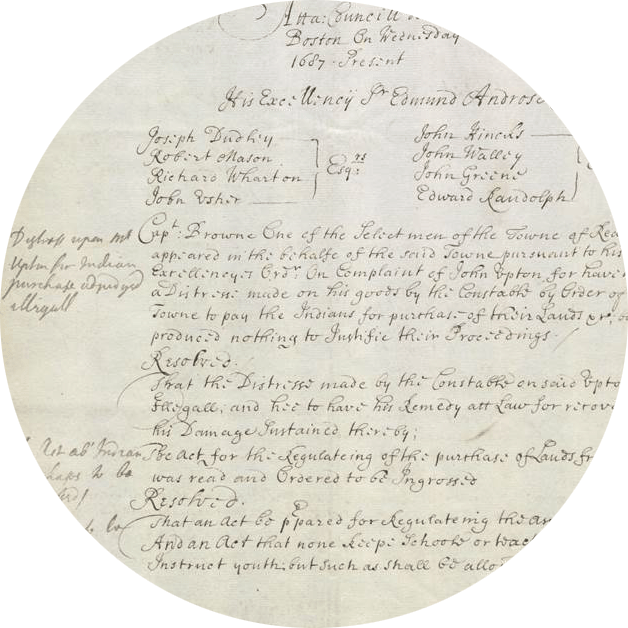

The Stuart Kings continued to consolidate power in the 1680s, forcing dissenters such as John Locke to seek exile in Holland and prosecuting others, such as Algernon Sidney, for treason. Charles II’s death in 1685 led to the accession of his brother James II to the throne. Both at home and across the expanding empire, James II’s accession set off a deep crisis. In the colonies, James II extended moves that his brother had already begun, to confiscate existing charters and to turn the five northern colonies into a government without any elected representation (the Dominion of New England). He had plans underway to create a complementary southern dominion. He also expanded slavery dramatically: the 1680s were the period of its greatest growth in England’s colonies under the aegis of the Royal African Company, which James II still headed, even while King.

At home, James II’s reign was tumultuous from the start, problems exacerbated by his not-so-secret conversion to Catholicism during his interregnum exile in France. Within months of his ascension, the Duke of Monmouth (Charles II’s illegitimate son) challenged James II for the throne. James II ultimately prevailed against the Monmouth rebels, and enacted swift and cruel punishments through his appointed judges, William Jeffreys in particular. News of the so-called “bloody assizes” traveled by word of mouth, as strict censorship made publication of the trial results nearly impossible until after James II was forced to flee into exile in 1688). Following the largely peaceful removal of James II, the “Glorious Revolution,” William and Mary’s ascension to the throne in 1689 led to a time of limited compromises on monarchical authority, dissent, and imperial reforms.

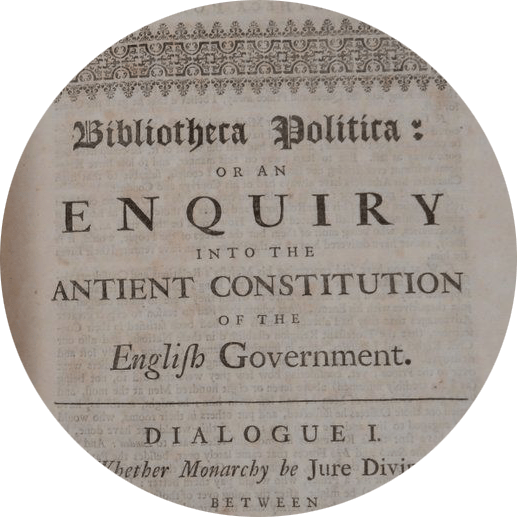

The period following the Glorious Revolution not only witnessed some of the most fierce, and open, debate about the nature and legitimacy of power in the English Empire, it also saw significant challenges to the institution of slavery.

The Dominion of New England