Policymakers are considering a variety of potential provisions for a forthcoming clean energy and infrastructure package, and one issue on the table is whether to extend or modify tax credits for plug-in vehicles.

Currently, a buyer of a new plug-in vehicle can earn a tax credit of up to $7,500. The amount depends on the vehicle’s battery size and whether the buyer owes enough federal income tax to claim the full credit. In addition, cars manufactured by certain automakers are no longer eligible, given that the subsidy phases out after a company passes 200,000 plug-in sales.

One obvious improvement, which seems likely to happen according to recent proposals, is to adjust the subsidy so that anyone can get it, regardless of their federal income tax bill. A different question also is being considered by policymakers: Should the subsidy be offered to any plug-in buyer, or should the subsidy favor lower-income buyers? Linking the subsidy to lower incomes would be consistent with President Joe Biden’s goal of factoring equity into climate policy, and since lower-income households are less likely than other households to buy plug-in vehicles, offering them larger subsidies could help boost the part of the market that’s struggling the most.

On the other hand, linking the subsidy to lower incomes could be a very expensive way to boost sales. A recent working paper examines a program in California that subsidizes plug-in vehicles for low- and middle-income households and finds that the program, while effective at boosting interest among these households, is costly. California would have to spend $9–14 billion to meet its goal of 1.5 million plug-in vehicles on the road by 2025.

Still, economic research to date hasn’t helped policymakers answer a broader question, which could address the effectiveness of subsidy programs more generally: Would adjusting the subsidies to favor lower-income households make the subsidies more or less effective at boosting sales?

According to economic theory, the answer is that it depends. On the one hand, low-income households tend to be more sensitive to vehicle prices. In other words, reducing a vehicle’s price could cause a bigger increase in vehicle purchases among lower-income households than among high-income households. If that’s the case, then offering larger subsidies to lower-income households could be more effective at boosting sales. On the other hand, lower-income households tend to have lower overall demand for plug-in vehicles. If a household isn’t even considering buying a plug-in, reducing its price seems unlikely to affect that household’s decision. In this alternative case, offering larger subsidies to lower-income households could be less effective at boosting sales.

If economic theory leads us to two conflicting answers here, then we can clarify by looking at the purchasing decisions of recent new-vehicle buyers to predict what would happen if federal subsidies were linked to lower household incomes. In recent working papers, my colleagues and I model consumer choices of new vehicles. We estimate the model’s parameters using survey data from more than one million households that purchased a new vehicle between 2010 and 2018. We assign each of these households to one of five groups based on their income, with each group roughly equal in size.

Figure 1 shows the percentage change in a vehicle’s sales if we hypothetically increase its price by 1 percent while keeping all other vehicle prices the same. Price increases discourage vehicle purchases by low-income households to a greater degree than other income groups, and disparities among income levels can be stark: the lowest-income group responds almost twice as strongly as the highest-income group to a 1 percent increase in vehicle price. (For context, the median US household income in 2018 was around $60,000.) This greater sensitivity among low-income households suggests that offering larger subsidies to low-income households could increase the subsidy’s effectiveness at boosting sales.

Figure 1. Percentage Change in Vehicle Sales Caused by 1 Percent Vehicle Price Increase

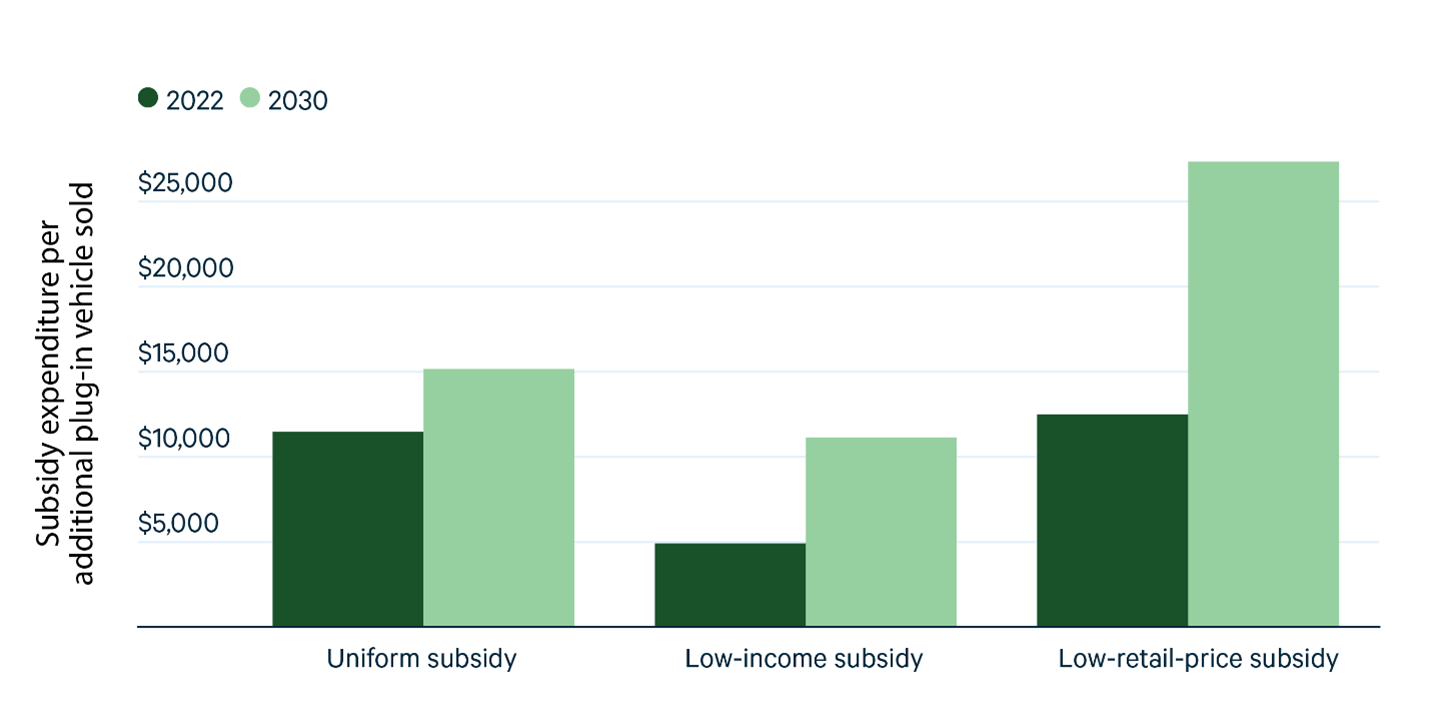

I used our computational model to compare a few hypothetical policies against a baseline that allows the subsidies to expire as they will under current law. The first policy provides a subsidy of $3,000 for any plug-in hybrid or electric vehicle, the second policy offers a subsidy only to the lowest two income groups, and the third policy offers a subsidy only to plug-in hybrid or electric vehicles with below-average prices for their category. This final option is motivated by the fact that many states link their subsidies to vehicle price. For accurate comparability, the subsidies are chosen to ensure that all three policies have the same total government expenditure. Here, I consider subsidies that are offered in two representative years, 2022 and 2030. Cost-effectiveness is the subsidy expenditure per additional vehicle sold, relative to current policy; this metric accounts for the fact that some subsidy expenditure goes to households that would have bought an EV even without a subsidy.

A subsidy offered to lower-income households increases sales more cost-effectively than the other subsidies (Figure 2). That’s because the lower-income households respond more strongly to subsidies than other households. These data also suggest that the 2030 subsidies are pricier per vehicle sold than the 2022 subsidies. This disparity is because, by 2030, plug-in vehicles are more competitive with gasoline-fueled vehicles, and a lot of the expenditure goes to households that would have purchased plug-ins anyway, with or without a subsidy. For context, in 2022, the low-income subsidy doubles the plug-in market share to about 4 percent, and in 2030, the low-income subsidy increases the market share from about 10 percent to 14 percent. The uniform subsidy and the subsidy for low-priced vehicles are substantially less effective.

Figure 2. Subsidy Expenditure per Additional Plug-in Vehicle Sold

As with any estimation of this sort, many assumptions underlie the numbers in the figures. Actually implementing a subsidy for low-income electric vehicle buyers would involve bureaucratic complexities, including a process to verify income. In addition, policymakers can consider other reforms to the subsidy; for instance, expanding subsidies so they apply to used plug-in vehicles could help make the program more equitable.

Still, these results demonstrate two important points. First, tying subsidies to lower household incomes may be more effective at boosting sales than other strategies. At least in this case of subsidies for electric vehicles, prioritizing equity does not trade off with effectiveness. Second, subsidies will be more effective in the near term and could be phased out in the future as electric vehicles gain further market share.

This article also appears on Resources for the Future’s Common Resources blog.