Guest post by Roxanne Jaffe and Yuheng (Gavin) Ding

Although public transportation ridership has plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic, e-scooter and bike-share companies as early as May 2020 expressed guarded optimism about the future of micromobility, spotting an opportunity to “capitalize on the public’s need for social distancing” while helping “avoid a return to pre-pandemic traffic levels” (Washington Post, 5/18/2020). As we enter the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, how have these alternative forms of transportation fared relative to city transportation systems? Have consumers substituted train and bus rides for e-scooter and bike-share trips? What does this mean for the future of the micromobility industry?

The micromobility industry came about as a solution to the last-mile transportation problem—that is, how to connect people to metro, train, and bus stops located farther than Americans’ average comfortable walking distance of less than a quarter mile from a trip’s origin and/or destination. In 2008, Washington, DC, became the first North American city to establish a docked, public bike-share system. Cities around the country followed suit to expand access to bicycle transportation, reduce traffic, and help meet environmental goals. Private companies responded to the growing interest in this type of transportation, and today, there are more than 20 firms across more than 130 US cities operating e-scooter, dockless bike-share, and moped platforms, all with the hopes of transforming the way we commute.

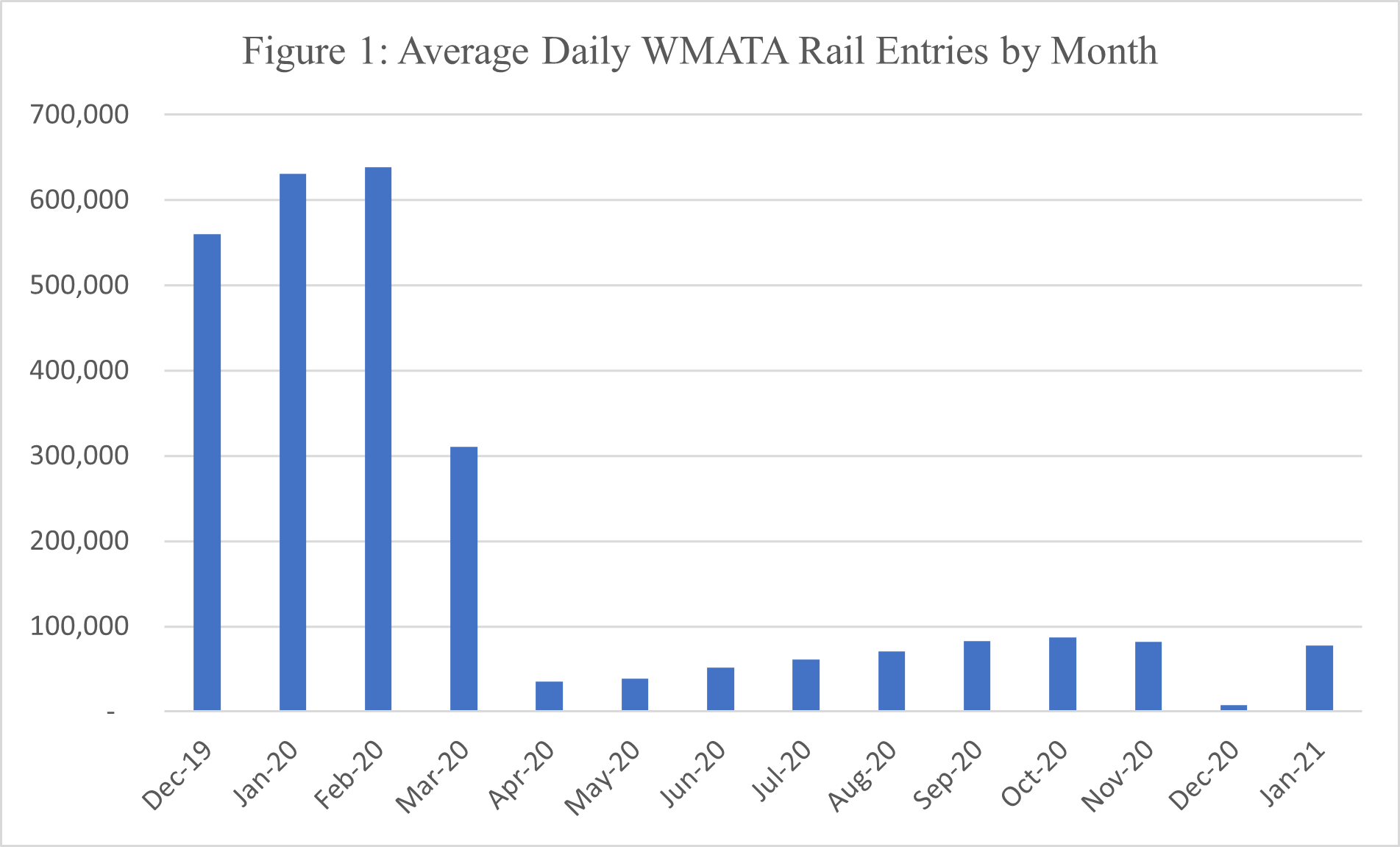

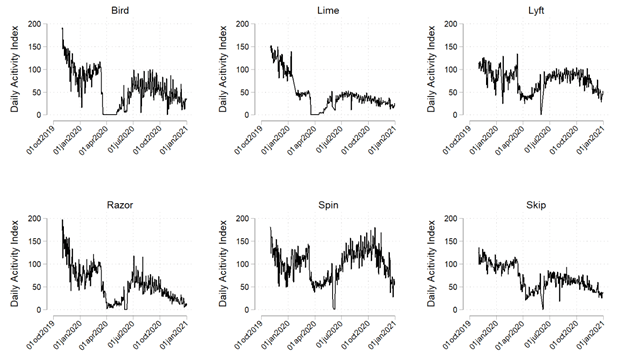

Especially given that the micromobility industry is still in its infancy, how has the COVID-19 pandemic affected its prospects? Using Washington, DC, as a case study, we see that the area’s metro transit and bus systems (WMATA) have taken a big hit as a result of the ongoing pandemic, even considering reduced train and bus offerings. Comparing January 2021 to January 2020, bus ridership decreased by more than 68 percent, and metro ridership declined by more than 87 percent (Figures 1 and 2). By contrast, e-scooter activities fell roughly 50 percent across all firms (Figure 3), outperforming public transportation but falling far short of industry’s expectation that these alternative forms of transportation would top their pre-pandemic numbers. And whereas recent trends in public transportation ridership are likely temporary, the impact of COVID-19 on the nascent micromobility industry may be more permanent.

Figure 3: Daily e-scooter activity, normalized to 100 (based on Dec. 31, 2019 level) by firm

One consequence of the pandemic for e-scooter and bike-share firms is that current supply outstrips demand for these products, forcing firms to partner up or get out and speeding what business scholars call the “shakeout stage.” In DC alone, 10 private bike-share and e-scooter firms entered the market, but not all of them remain.

In fact, the consolidation of firms slowly started before the pandemic with the acquisition of two of the industry’s smaller firms, Ojo and Scoot, by Gotcha and Bird, respectively. Then, during the pandemic, two much larger acquisitions took place, further consolidating the industry to a few key players. First in June 2020, Lime acquired Uber’s scooter and bike-share fleet (JUMP) for roughly $170 million—a deal almost 8 times larger than Bird’s acquisition of Scoot and 14 times larger than Gotcha’s acquisition of Ojo. In December 2020, Helbiz acquired Skip for an undisclosed amount then merged with the publicly traded firm GreenVision the following February, making Helbiz the first micromobility firm listed on the NASDAQ.

While the pandemic’s final toll on public transportation and the micromobility industry is still unclear, people have returned to scooters and bikes at higher rates than buses and trains. This has likely introduced bicycling and scooting to new customers, so that when in-person work resumes, and restaurants, bars, and entertainment venues fully reopen, we likely will see an increase in the use of these alternative forms of transportation. If so, the next step will be for local governments to help accommodate the increase in micromobility ridership to make this type of transportation safer, improve traffic flow, and meet environmental goals.

Roxanne Jaffe is a PhD candidate in managerial economics and Yuheng (Gavin) Ding is a PhD candidate in strategic management and entrepreneurship at the Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland.