This is a guest post by Nick Molden, Founder & Chief Executive Officer, Emissions Analytics

The official story is that emissions regulations in the European Union (EU) have become relentlessly tougher since “Euro stages” were introduced in 1992, of which the current Euro 6 stage is the toughest yet. If only the progress were this smooth.

In reality, many European cities are experiencing persistent air pollution problems, thanks to a preference for diesel vehicles combined with real-world diesel emissions that greatly exceed laboratory results. On-road testing has helped bring emissions down, but the EU—stung by the VW Dieselgate scandal—is now potentially swinging to hypervigilance. What can the EU learn from past implementation of its emissions rules?

European emissions standards were introduced in the 1990s to tackle a mix of tailpipe pollutants, including nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulates from diesels, and carbon monoxide and unburnt hydrocarbons from gasoline vehicles. The structure of the standards shares many similarities with US EPA’s tier-based emissions standards, and in both regions compliance was based on laboratory emissions testing.

Rapidly, three-way catalysts tackled both of the gasoline pollutants, and particulate filters solved smoke from diesels, reducing particle concentrations in the air. However, a NOx emissions problem was looming. Many cities in Europe developed—and to this day wrestle with—frequent violations of standards set for nitrogen dioxide, which reacts with other chemicals to produce particulates, ozone, and acid rain.

The problem has its roots in Europe’s embrace of diesel technology. About 20 years ago, motivated by reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) and the associated climate change agenda, many governments in Europe started introducing incentives for consumers to buy diesel rather than gasoline cars. The rationale is that diesel engines get better mileage and emit less CO2 than their gasoline counterparts (even though they emit far greater NOx). The incentives were successful, and diesels accounted for 55% of new vehicle registrations in the EU at their peak popularity in 2011.

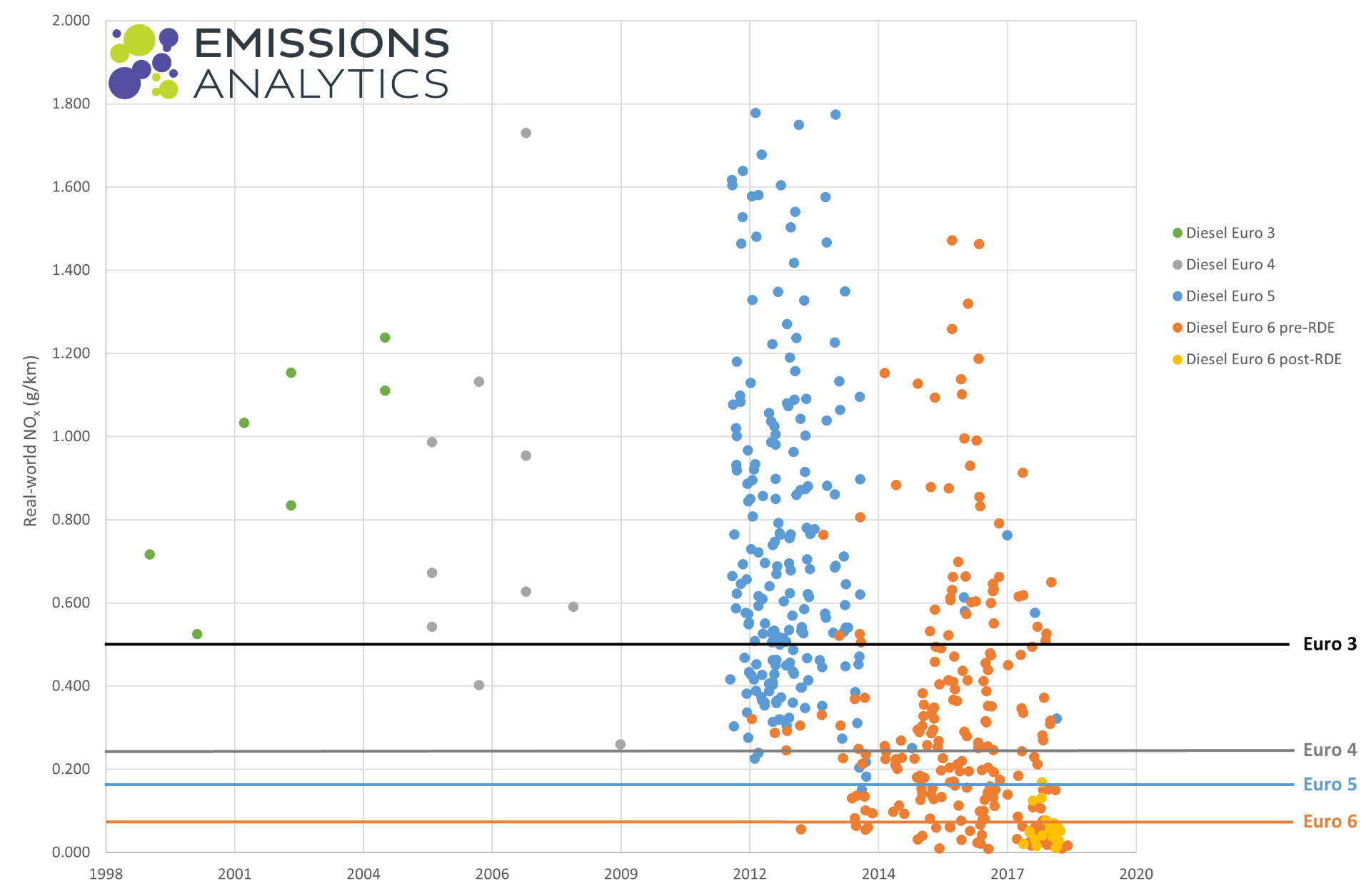

The Euro 3 standards set a NOx emissions limit of 500 milligrams per kilometer (mg/km), and compliance was assessed based on laboratory tests. Real-world emissions were similar to the Euro 3 limit. The NOx limit was reduced progressively through Euro 4, 5 and 6, and governments assumed that these would take care of any problems with diesel NOx emissions.

Instead, as the limit got lower, rather than reduce real-world NOx emissions, it proved easier for many manufacturers to use leniencies and ambiguities in the European regulations—not present in superficially similar US regulations. By Euro 4, the regulated limit halved, but real-world emissions hardly moved. By Euro 5, emissions were three to four times the limit and, and by Euro 6, they were four to five times higher.

The figure below, based on an independent, real-world test program undertaken by Emissions Analytics shows that between 1999 and 2017 real-world NOx emissions were stuck at around 0.5g/km. By comparison, gasoline vehicles averaged 0.03g/km.

Since 2017, however, tailpipe NOx has fallen 92% to an average of 0.05g/km. What happened?

The introduction of Real Driving Emissions (RDE) in 2017 was the immediate cause of the shift. Rather than fix the laboratory test cycles and protocols for assessing compliance, Europe turned to on-road verification of official certification results. Verification relies on Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS)—equipment that had been developed in the US in the 1990s but had not been used in Europe. Dieselgate in 2015 accelerated RDE’s deployment, and the automotive industry was unable to forestall tougher terms. They responded with a technological solution to achieve the reductions, adopting Selective Catalytic Reduction, which converts NOx to water and nitrogen.

Regulators are discussing Euro 7 standards, which are touted as the last stage before full electrification of the light-duty fleet. Recent discussions indicate that Euro 7 could take one of three forms. At the lightest end is a tidy-up of Euro 6 and alignment of the gasoline and diesel standards. A second alternative could see significantly lower limits and the inclusion of new, currently unregulated pollutants, like formaldehyde and nitrous oxide. On top of that, lifetime tracking of vehicle emissions via on-board telematics is being considered.

The first level is sensible and urgently needed. The second and third levels would likely add sufficient burdens to the manufacture of vehicles and costs to consumers to compromise the economic future of the internal combustion engine. This may be exactly what the European Commission wants in the pursuit of CO2 reduction. However, from a purely air pollution point of view, Emissions Analytics’ modeling shows that emissions from RDE vehicles are sufficient to meet ambient air quality laws.

Based on that track record, the danger is that the EU instead will set tough-sounding rules and then undercut their force with poor execution. This is a present and immediate concern with plug-in hybrid vehicles in Europe, where real-world CO2 is double or triple the official values based on the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP). Why is this not being addressed, when the problem is known? Perhaps the answer is that both industry and governments officially see plug-in hybrids as only a brief stepping stone to all-electrics. But is this setting up the next potential emissions regulation crisis, with the EU doomed to repeat the pattern of Dieselgate?