I Resist This from March 4 to April 6, 2024 at The Stamp Gallery | University of Maryland, College Park | Written by Reshma Jasmin

The first time I visited Stamp Gallery’s I Resist This was on its fourth day open. The current exhibition takes the form of an artist residency, which means that the artist, Charlotte Richardson-Deppe, would be working on the pieces for the exhibition in the gallery itself throughout the course of the program. I had met Richardson-Deppe prior to this exhibition, but I didn’t know her in the context of her work as an artist. I also had never encountered a behind-the-scenes look into the artistic process serving as an artform itself. As such, I was looking forward to talking to her about the inspiration behind her choice to perform her process and watching her in action. But on my first day in the gallery, I was alone. A bit later, someone came in, and commiserated with me about not seeing Richardson-Deppe. But she noted that she saw traces of Richardson-Deppe’s presence over the course of hours or days— in Crocs which had been moved and through progress on a textile piece that was splayed out on benches.

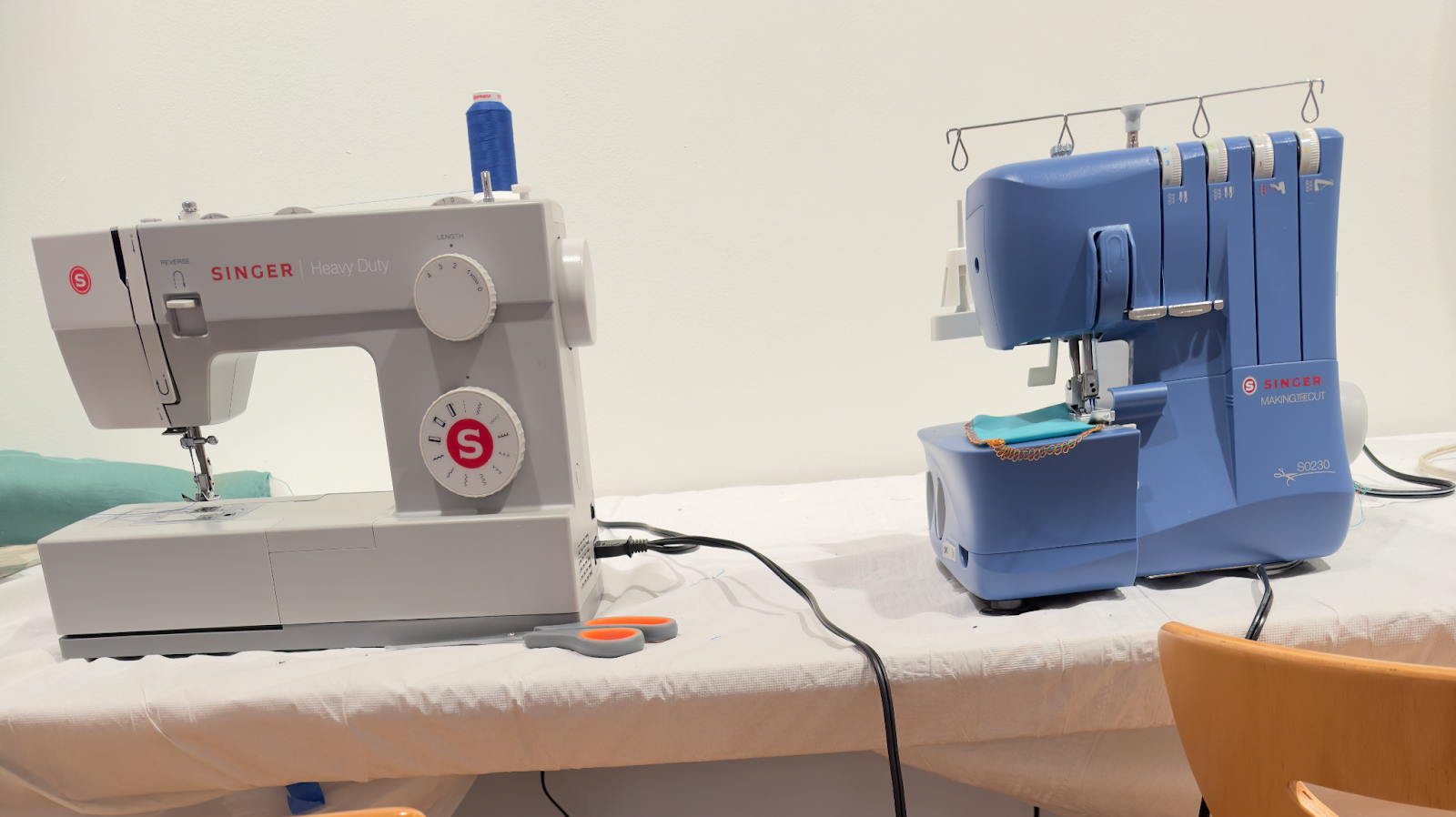

When I came in the next day, I did see Richardson-Deppe, and I was able to chat with her and watch her work for hours. I learned about the function of her two sewing machines; one that was well equipped for heavier fabrics (machine on the left) and the other that was meant only for hemming (machine on the right). She told me about her thrift-store strategy of buying a large quantity of cheap clothes and how she mostly collected sweaters, pull-overs, sweatpants, and leggings by chance, but that such heavier materials held up longer for her wearable creations.

Stamp Gallery on March 15, 2024

Stamp Gallery on March 15, 2024

I Resist This is an exploration of interdependence versus independence, and, in many ways, serves as social commentary about the futile desire for complete independence and the simultaneously undeniable need for social support. To one of the many UMD art courses that visited the gallery, Richardson-Deppe described how she wanted to make visible the invisible relationships and networks and explore different social dynamics. e also mentioned that her wearable pieces did eventually rip during performance, but that it was an expected and welcome end. She informed me that she also teaches in the art department, and I came in during the exact hours she taught a class the day before. I was relieved that I’d be able to see Richardson-Deppe once a week, so the disappointment of the day before dissipated. But the movement of her Crocs lingered in my mind. Why was the sign of previous presence more melancholic than absence alone?

Whenever I was in the gallery sans Richardson-Deppe, I’d look for her Crocs, and sure enough, they’d be in a different location than when I last saw them (See if you can spot them in the photos below!). It was comforting to know she had been there, but she also felt just out of reach. Would I see her again? Absolutely, and it would often be the very next day, and I knew that. And yet, each time I didn’t see her, I felt as though we were two ships passing in the night.

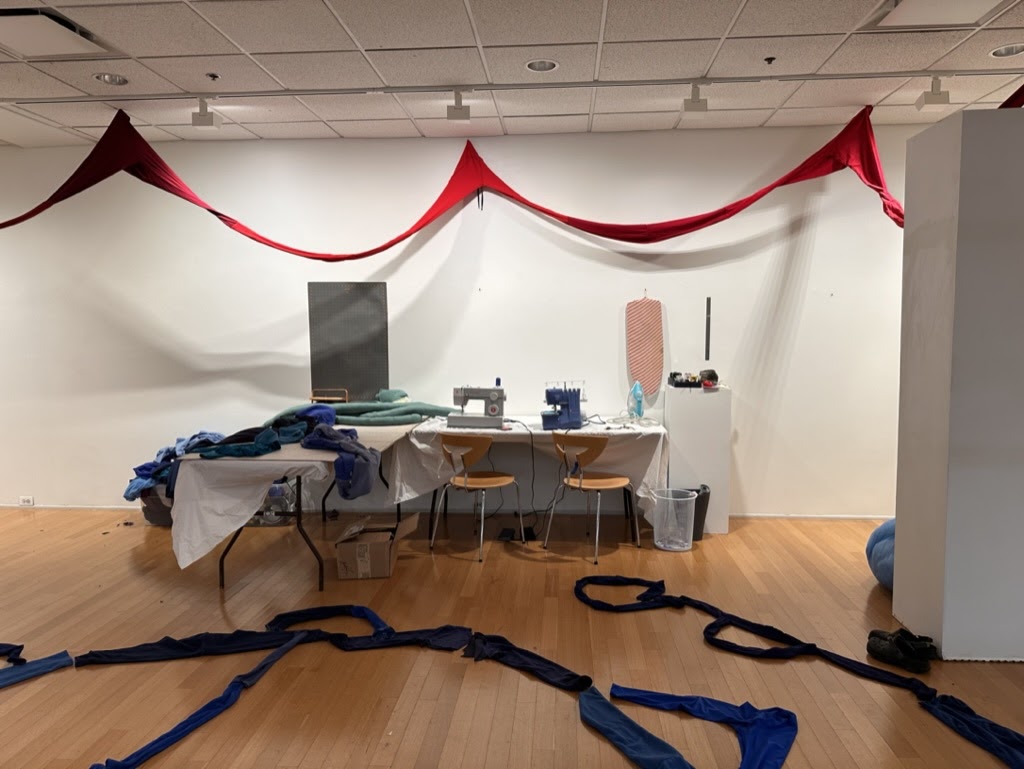

Stamp Gallery on March 15, 2024

Stamp Gallery on March 15, 2024

Stamp Gallery on April 05, 2024

Stamp Gallery on April 05, 2024

My expectations all came from the descriptor: Artist-In-Residence. “___-in-residence” is most commonly used for professors, artists, poets, etc. This use comes from the definition of “resident” from the 14th century Medieval Latin word residentem and/or residens, which refers to one who dwells in one location to fulfill their duty in a Christian mission/obligation sense. The phrase “___-in-residence” and the expanded context of the definition only began showing up in the 19th century.

Related to resident is residence, or in Medieval Latin, residentia, which means is one’s dwelling place or the act of dwelling in a place. These words are derivatives of residere, which is Medieval Latin for reside. The broken down meaning is “re-”: back, again and “sidere”/“sed”: to sit. Together, residere means “sit down, settle; remain behind, rest, linger; be left.”

Richardson-Deppe’s pieces rest, remain, and are left behind while she’s not in the gallery. But Richardson-Deppe also lingers and settles in the gallery during the moments she herself is absent from the space. The growing piles of soft sculpture, the textile pieces approaching completion, the ever-changing composition of the items resting on her worktable, and of course, the silently moving Crocs all continue her performance of creation. The fact that all such changes occurred are signs of life, signs of Richardson-Deppe.

I Resist This is an exploration of interdependence versus independence, and, in many ways, serves as social commentary about the futile desire for complete independence and the simultaneously undeniable need for social support. To one of the many UMD art courses that visited the gallery, Richardson-Deppe described how she wanted to make visible the invisible relationships and networks and explore different social dynamics.

Charlotte Richardson-Deppe, Red (2023), Screenshot from video. Performers: Gwyneth Blair, Lisa Dang, Sarah Gnolek, Amanda Murphy, Charlotte Richardson-Deppe, Kat Ritzman, Jill Stauffer, Allie Wallace, Jackie Wang.

Charlotte Richardson-Deppe, Red (2023), Screenshot from video. Performers: Gwyneth Blair, Lisa Dang, Sarah Gnolek, Amanda Murphy, Charlotte Richardson-Deppe, Kat Ritzman, Jill Stauffer, Allie Wallace, Jackie Wang.

The relationship between an artist and their labor is typically invisible; most exhibitions only display completed artwork, and even if an artist is present at times to discuss their process and inspiration, we don’t get to see them at work. Through her residency, when Richardson-Deppe is in the gallery, her hands on the textiles and sewing machine are seen; as the maker she is part of her work. However, even residents of homes leave to fulfill their other responsibilities and live out other parts of their lives. One part of being a “resident” involves leaving and returning, being absent and present. In the moments when Richardson-Deppe is not in the gallery, the connection to her work that was once visible disappears. Yet, though we do not see her, we still unconsciously perceive her presence in the changes to her work and workspace. What is invisible is still there, even if it only exists in the abstract understanding that change occurred and someone was responsible for it. Like Richardson-Deppe suggests through her work, even invisible relationships are inarguably present.

Stamp Gallery on March 15, 2024

Stamp Gallery on March 15, 2024

Stamp Gallery on April 05, 2024

Stamp Gallery on April 05, 2024

Humans look for signs of life everywhere. In space, we search for biomarkers, water/ice, radio waves, pollution. In biology, we look for order, sensitivity or response to the environment, reproduction, growth and development, regulation, homeostasis, and energy processing. In my homes, I look for whose shoes are present and which ones; I notice what food in the fridge is slowly decreasing and whether things have been shuffled around; what the arrangement of dishes in the dishwasher looks like; what doors are open; whether there are lights turned on and which ones. I look not only for signs that someone was home or not, but also for signs of who specifically is, and what they might be up to, how they feel.

Even when their presence is dubious, we look for people. Regardless of how lonesome we feel, when we search for people, and even when they aren’t around, we find them. Sometimes, we’re not even looking for them but we feel them throughout their absence nonetheless. Even when Richardson-Deppe isn’t in the gallery, she lingers.

Our presence in each others’ lives is irrefutable and irrevocable. People come and go, but there are always the traces they leave behind. And as melancholy as it is to feel each other linger, there’s a comfort in knowing that people are always around us, that they always stay with us.

Charlotte Richardson-Deppe’s work is included in I Resist This at The Stamp Gallery of the University of Maryland, College Park, from March 4th to April 6th, 2024. Richardson-Deppe will end her artist residency with the performance I Resist This on April 6th, 2024 at 7pm.