Mark Townsend, Agriculture Agent Associate | mtownsen@umd.edu

University of Maryland Extension, Frederick County

Grain markets have slid significantly from the highs posted last summer that followed the perceived drought in the Midwest.

Unfortunately, these drought concerns were generally unfounded as key growing areas received timely rains to keep yields from suffering in the corn belt. In fact, the U.S. set a new corn production record at 15.234 billion bushels topping the previous record set in 2016 at 15.148 billion bushels. The trifecta of a record large U.S. crop, a large Brazilian corn crop, as well as underwhelming domestic and export demand sent prices spiraling lower from August 2023 to February 2024. The March ‘24 Corn contract traded at three-year lows on February 26th dipping below $4 following 11 consecutive week-over-week price declines.

Soybeans were unfortunately no better, falling $2.90 from their summer high ($14.18) to their low ($11.28) in the March ‘24 contract. Much of the same stories plagued this market including an unrealized weather rally and outstandingly large South American production that punished U.S. export demand.

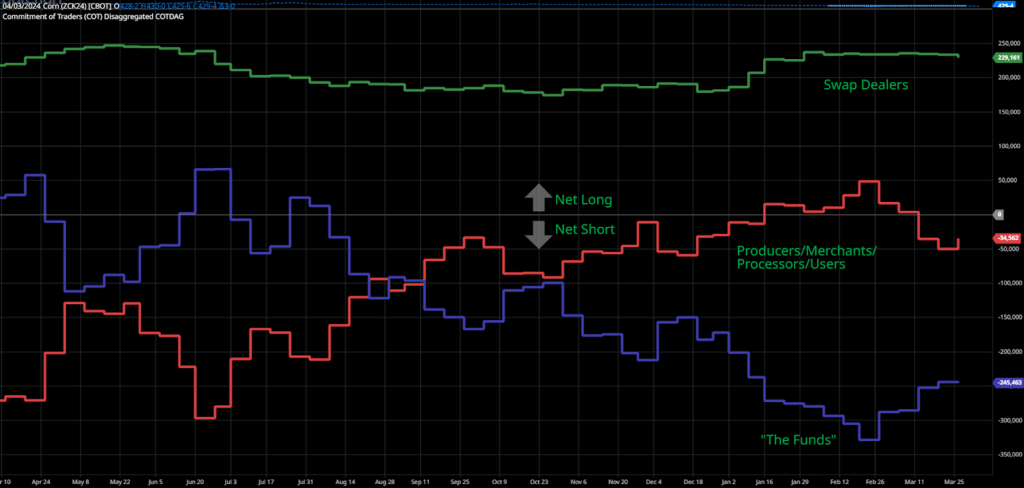

To add insult to injury, “the Funds”—traders in the market who manage money for clients as either hedges or other investment strategies hit a record 340,732 net short position in the corn market on February 20th. Simply stated, these traders placed the largest-ever bet on corn prices continuing to decline, which has placed a metaphorical wet-blanket on any hopes of a rally.

Today

Grains have rallied from the end of February and throughout March. The inflection point was the last day of notice for March hedge-to-arrive (HTA) contracts. To that point, sellers (farmers, dealers, etc.) had the choice of pricing corn at current prices or “rolling” the contract to the May contract. The bleak outlook forced many hands and stimulated selling which pulled prices lower until the selling pressure was over.

Since then, both the corn and soybean markets have rallied off the lows and recovered to price levels previously seen in early February. The upward momentum has been driven by a phenomenon known as “short covering” that creates a positive feedback loop–the more it happens, the more it happens. As prices rise, “The Funds” in their net short position lose money as their bet has turned against them. To stop this, they must exit their position by buying a contract to offset the one they previously sold1. The buying stimulates further price increases that induce another fund manager having to offset their short position. At its extreme, this feedback loop can throw prices to astronomical levels2. In this case, the bump is a welcomed change but is unlikely to send us much higher for now.

More recently, the USDA released its Prospective Plantings Report compiled from surveys asking farmers their planting intentions this season. The report suggests growers will plant 90 million acres of corn and 86 million acres of soybeans, indicating that growers are shifting acres away from corn to soybeans. This was unsurprising, however traders found this as good news as the nearby contracts in both markets traded higher the day of the report. However, traders are generally wary of this recent report given the low farmer response rate and the tendency for acreage figures to climb with subsequent USDA planting reports.

Season Outlook:

The saying, “all models are wrong, but some are useful” may hold true for commodity market predictions as well; there is a significant degree of uncertainty in any market that can render any forecast absolutely incorrect. As such, this is not meant to be a forecast but more of an observation of trends and conditions that may prove useful.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

Every market most fundamentally relies on the interplay between supply and demand. Currently in the grains, supply has outstripped demand. Following last year’s record crop, U.S. corn supply is almost burdensome.

A common metric that evaluates how efficiently we use the crop we grow is the Ending Stocks-to-Use (S/U) ratio derived from the USDA World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimate (WASDE) each month. Currently, the USDA projects the 2024/25 ending stocks (that which we will not use from the crop we’re about to plant) at 2.53 billion bushels and an S/U ratio of 17.2%–a level we have not seen since the 2006 when corn traded at an average price of $2.62/bu. This current 2023/24 marketing year (ending Sept. 1, 2024) is currently pegged at 14.9% S/U ratio–well higher than the 7-10% range of the last three years and the 12.6% historical average.

The soybean side of things is only marginally better and certainly not rosy by any stretch. The current S/U ratio projection for this year’s crop is 9.9% with the current marketing year sitting at 7.6%. Both these figures are a far cry from the burdensome supplies we accrued during the 2018-2019 trade war with China (22.9% S/U) yet they signal a surplus of soybeans.

Market Movers

With the current fundamentals dreary at best, it’s pleasant to think of those things that could actually help prices higher.

- Midwestern drought conditions continue to worsen throughout the growing season. US weather conditions are a significant driver of price action in the growing season–as exemplified by last year. Currently, some of the Midwest is experiencing a moderate drought, with some agronomists questioning the subsoil moisture levels before planting. Importantly, drought conditions would have to persist throughout the growing season well past planting. Generally, drought is bearish to corn in April and May as Midwest growers can plant at a breakneck pace just in time for timely rains that pull yields higher and prices lower. As evidenced by last year, corn did not rally until late-May over weather concerns and in 2012, corn did not rally until mid-June. Both these years indicate that prices will likely stay mixed until real concern over crop condition emerges during the growing season.

- The South American (Brazil + Argentina) soybean production is lower than expected, improving export demand for U.S. soybeans. Soybean harvest in Brazil is nearing completion, however final production estimates remain volatile. The same is true with South American corn production: a supply-side shock could support U.S. corn prices. Brazil has completed corn planting this last week of its large safrinha corn crop. Currently, much of the key corn growing regions are in a minor drought or have experiences greater than normal rainfall. More serious and persistent crop-damaging weather events could certainly be a boon to the U.S. market.

- Recently, the Federal Reserve signaled that it will likely keep the Federal Funds rate higher for longer–increasing borrowing costs. If this holds true, investors may find themselves less attracted to debt and equity markets as companies may have a more difficult time generating earnings. Instead, investors may revert back to commodities–a market often seen as a hedge against inflation–as they did in 2022. As mentioned above, this may trigger a significant unwinding of short positions which could carry the market to higher prices. Unfortunately, this is likely the most unlikely scenario for increasing commodity prices as equities soar to all time highs in recent weeks.

So What Can We Do About It?

Marketing grain in 2024 will likely be challenging on all fronts. Put another way, given the current outlook, it is incredibly unlikely that selling grain in the fall at harvest prices will be a winning strategy. Similarly, it’s unlikely that an unhedged, unpriced JFM ‘25 sale will offer anything better as there are additional storage costs involved. That said, developing a preharvest marketing strategy may very well be a key to success this marketing season. Betting on the aforementioned weather stories is hardly a marketing plan.

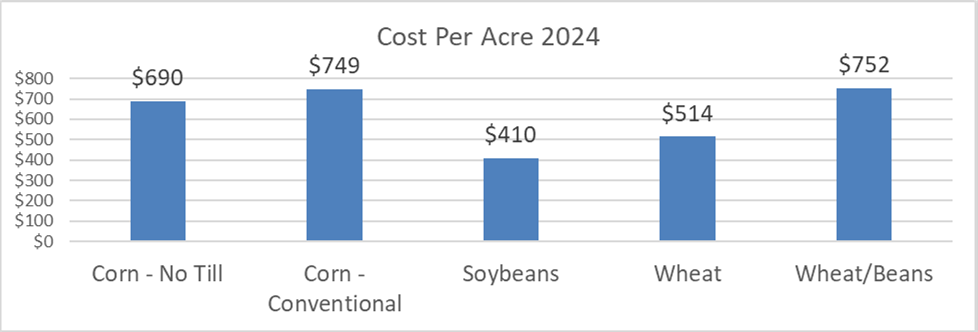

Like every year the first step is knowing your cost of production inside and out. Marketing opportunities will present themselves, but it will take knowing what is and what is not a good price. With today’s relatively high input costs, “yielding your way out” of low prices is more challenging than previous years. Therefore it may be more crucial than ever to make judicious agronomic decisions.

Take advantage of seasonal market patterns. Generally speaking, we see 3-6% increase in corn and soybean prices between mid-March and late-May from their post-harvest lows in January. As old crop marketing wanes, and concerns over the current year’s crop emerges (like the weather), prices rise slowly during this time. It may be best to price some grain sooner rather than later to take advantage of this general trend. Put it more directly; from May 1st to October 1st, corn prices fall more than $0.30, 74% of the time. Would you bet on something weighted 75% against you?

Track local basis. Generally, basis tends to follow broader market conditions especially when it comes to spreads between nearby and more distant contracts. Seasonal trends in basis also exist with harvest often being the low point and spring generally higher.

Keep a watchful eye on the markets this season. It may be such that prices are favorable for a day or two before they fall back lower.

Please also consider attending a University of Maryland Extension grain marketing meeting. These meetings are filled with all the above strategies, general information, and more that could help you with your marketing decisions.

Best of luck to you all. Here’s to blue skies and high prices!

Footnotes & References:

1 This may seem counter-intuitive. For a review on futures contracts please visit CME’s Self Study Guide to Hedging with Grain and Oilseed Futures and Options.