Alium crops: Scout fall leeks, garlic, and other Allium species from now until the first freeze for Allium leaf miner egg-laying damage. Damage consists of a row of several small round white dots that appear on the leaf blades (fig 1). Larvae will live inside the leaves before moving down to the bulbs, where they feed and eventually pupate and overwinter. Row covers can be used to exclude this pest when Alliums are first planted. For organic production, spinosad works well in controlling the larvae. Two or three applications of the insecticide about ~2 weeks apart from each other once oviposition marks are seen should offer good control of this pest. Using a penetrant adjuvant such as neem oil is recommended for better control.

Cole Crops/ Brassicas: Check young plants for flea beetles. The thresholds for flea beetles are one per transplant or five beetles per 10 plants. Downy mildew and Alternaria can be a problem in fall brassica crops. When the disease first appears, apply a fungicide every 7 to 10 days. Continue to scout all fields for caterpillar pests (armyworm, diamondback moth larvae (DBM) (fig 2), and cabbage looper larvae). Treat crops when 20% of the plants are infested during the seedling stage, then 30% infestation until the cupping stage. Use a 5% threshold from early head to harvest in cabbage and Brussels sprouts. For broccoli and cauliflower, use 15% at curd initiation/cupping, then 5% from curd development to harvest. If treatment is needed, adjust your spray pattern so the spray goes sideways and gets on the undersides of leaves, particularly when using BT and other contact materials. Bt and Copper are not compatible and should be apply 24 hour apart from each other. Due to resistance development, pyrethroid insecticides (Group 3A) are not recommended for the control of diamondback moths. Re-scout treated fields within 3 days to assess the efficacy of the insecticide applications. Effective materials should eliminate DBM larvae within 48 hours.

Sweet Corn: CEW numbers have been declining due to cooler nights, but traps around us are still recommending a 3-4 day spray schedule for silking corn. This week’s predicted rain should also reduce their number.

Lima Bean: Check lima beans for soybean looper and stink bugs. Looper activity should decline once nighttime temperatures drop into the low 50s.

Swiss chard, Beets & Spinach: Check for beet webworm (fig 3). Its habit of enclosing itself in folded leaves protects it from insecticides and natural enemies. Insecticides are most effective in controlling small caterpillars instead of those that are nearly full-grown and not eating as much.

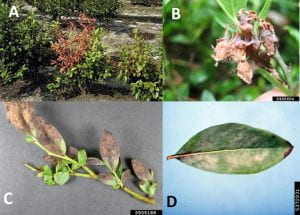

Pumpkins: Continue to check for aphids, squash bugs, and mealworms. For melon worms (fig 4), check the undersides of partially shredded leaves and look at the rinds of pumpkins to determine if they are attacking the fruit.