Corn earworm moths counts in pheromone traps have been increasing over the past few days in some areas in Maryland and Delaware. Sweet corn growers should keep an eye out and consider shortening spray intervals to a 2 to 3-day spray schedule while others could still be around a 3 to 4-day spray schedule.

Tag: IPM

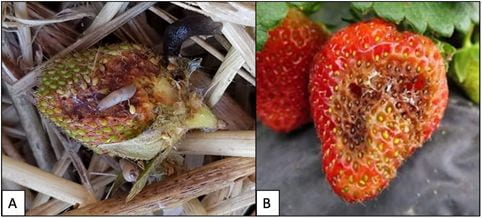

Who has Been in My Strawberries? Slugs and Sap Beetles, Two Common Insect Pests on Strawberries.

By Sankara Ganesh, Maria Cramer, and Kelly Hamby.

Department of Entomology, University of Maryland, College Park

The cool, wet spring weather we have been experiencing favors slugs, so be on the lookout for slug damage. Slug damage may easily be confused for sap beetle feeding, but management of these pests is very different, so it is important to correctly identify the problem. Both pests can be common in matted row production.

Damage: Slug feeding renders fruit unmarketable and susceptible to infestation by other pests including sap beetles. Sap beetle adults are attracted to ripening, ripe, and overripe fruit and directly cause damage through feeding, but may also introduce pathogens and contaminate fruit with larvae. Sap beetles tend to leave behind circular holes while slug damage is often irregularly shaped, and both can cause moderate to deep holes. However, slugs will also feed on leaves and leave behind slime trails. Monitoring is important to conclusively determine which pest is causing damage.

Strategies for Effective Management of Botrytis and Anthracnose Fruit Rot in Strawberries

Strategies for Effective Management of Botrytis and Anthracnose Fruit Rot in Strawberries

Dr. Mengjun Hu, Univ. of Maryland, and Kathy Demchak, Penn State Extension

Managing gray mold (Botrytis) on strawberries is increasingly challenging because of fungicide resistance development, plus a new Botrytis species that is less susceptible to fungicides is becoming common in the mid-Atlantic region. Resistance to certain fungicides is also a problem in management of anthracnose fruit rot. This article describes disease management strategies designed to slow further resistance development, while also providing specifics for managing our two most common fruit rots.

First, what’s new with Botrytis. There are at least 4 species of Botrytis that can infect strawberries, but only two of them have been commonly found in the region. Botrytis cinerea, the species traditionally infecting strawberries, is present nearly everywhere and affects many horticultural crops. Recently another species, Botrytis fragariae, has also been found and as its name indicates, is more specific to strawberry plants. It appears to overwinter on strawberry plant tissue, and preferentially colonizes blossoms early in the spring, causing them to “turn brown and dry up”. While sometimes only one of these species is present, both can be present at the same time in a field and even in the same blossom. Using certain fungicides selects for resistant strains of either species, and also preferentially selects for one species over the other. This means that both species have resistance to multiple fungicide groups, and both species can survive in fungicide-treated fields.

How can you tell if the newer species of Botrytis might be present in your fields? While B. cinerea (the traditional species) is often isolated from both flowers and fruit, B. fragariae (the new one) is often isolated from flowers, and it has been shown that B. fragariae infection was much more aggressive on strawberry flowers than fruit. If you see larger-than-usual numbers of blossoms turning brown and shriveling (not to be confused with frost damage, which blackens the center of the flower), it may be prudent to choose fungicides as if B. fragariae presence had been confirmed in your field. If you see no more symptoms on the flowers or buds than usual, you may be able to assume that the new species isn’t present, or at least not to a great extent.

Allium leaf miner

Allium leaf miner Phytomyza gymnostoma is a pest on chives, scallions, garlic, onions, and leeks. Overwinter ALM across the Mid-Atlantic will be emerging soon. Start scouting for ovipositor markings made by female ALM over the next few weeks on food and ornamental Allium crops. These markers will be neat rows of white spots descending from the upper tips of allium leaves. These marks will be typically be seen on the tallest leaves first. ALM Larvae mine leaves and moves towards and into bulbs and leaf sheathes. The leaf punctures and mines serve as entry routes for bacterial and fungal pathogens.

Spring crops are usually not as hard-hit as fall crops, especially when looking at leeks, but this pest has steadily increased its geographical range each year and its damage potential. If you had some infestation last year, you will especially want to look for this pest’s signs.

Yellow sticky cards or yellow plastic bowls containing soapy water can be used for monitoring but are not affected control independently.

Onion leaf blades showing round white dots made by female Allium leaf miners. Photo by Jerry Brust

Cultural Control: Covering plants in February, prior to the emergence of adults, and keeping plants covered during spring emergence, can be used to exclude the pest. Avoiding the adult oviposition period by delaying planting (after mid-May we think) has also been suggested to reduce infestation rates. Covering fall plantings during the 2nd generation flight can be effective. Growing leeks as far as possible from chives has been suggested. Organic

Chemical Control: Azadirachtin (Aza-Direct or other formulations) or spinosad (Entrust or other formulations) follow label instructions for leaf miner.

Synthetic Chemical Control: Systemic and contact insecticides can be effective. EPA registrations vary, however, among Allium crops. Check labels to ensure the crop is listed, and for rates and days-to-harvest intervals. Options that may be effective include cyromazine (Triguard), dinotefuran (Scorpion), spinetoram (Radiant), lambda-cyhalothrin (Warrior II or other formulations), and abamectin (Agri-Mek or other formulations).

Mowing: a casually thought of integrated weed management tool

By Cerruti R2 Hooks$ and Dwayne Joseph*

$Professor and Extension Specialist, *Post-Doctoral Fellow, CMNS, Department of Entomology,

Mowing is a relatively inexpensive form of mechanical weed control that can reduce the use of tillage, herbicide and manual weeding. It may serve as an alternative to herbicide and cultivation or part of an integrated approach. However, mowing to manage weeds has not been well studied compared to other IWM tools and is more popular in habitats with perennial stands of vegetation. Consequently, limited information is available on mowing use in crops. As such, it is not adaptable to numerous cropping systems; and partially for this reason, it is used mainly for aesthetic reasons and preventing seed production in perennial stands of vegetation neighboring cropland. Still, research has shown that mowing can be used jointly with other weed management tools such as applying herbicides, cover cropping and growing competitive crops. Mowing may also be used to successfully manage perennial weeds by removing the aboveground plant parts and consequently reducing food reserves in their storage organs. This, however, may take multiple years and the integration of other weed management tactics. Some research has found that combining mowing with herbicides enhances perennial weed control. Still, there are advantages and disadvantages of using mowing as a weed management tool. Mowing generally does not have any negative environmental effects. However, many weeds especially those that grow close to the ground such as buckhorn plantain are naturally tolerant of mowing. As with any IWM program, it is important to “keep weeds guessing” by utilizing different management tactics; and mowing is no exception to this rule. For example, repeated use of mowing as a single weed management tactic may result in a selection pressure or shift to weed species or genotypes that can reproduce even if repeatedly mowed. These species may overtime become more difficult to manage. As such, in those situations where mowing is practical, one should consider making it part of an overall IWM program. Financial support for the publication of this article is via USDA NIFA EIPM grant award numbers 2021-70006-35384 and NESARE – Research for Novel Approaches (LNE20-406R).

Blueberry IPM Post Bloom – Diseases Pathogens

By Haley Sater

Agriculture Agent, Wicomico County

University of Maryland Extension

HSater@umd.edu

( Article from May 2021 issues of UME Fruit and Vegetable Newsletter)

Most blueberry cultivars here in Maryland bloomed and green fruit are developing. Now is the time when a variety of pathogens and pest will begin to take up residence in your field which can harm your developing crop. It is important to perform routine scouting throughout your farm and make sure that you’re not seeing symptoms of some of

the common pests and pathogens. Below is a description of several of the most common diseases and pests you may find at this time in your blueberries.

Pathogens to be on the lookout for:

During the cool, wet days where temperatures do not reach above 70 degrees you may begin to see symptoms of several fungal pathogens including botryosphaeria canker or stem blight, botrytis, anthracnose and powdery mildew. These conditions make for an ideal environment for some of these fungal pathogens to grow or spread.

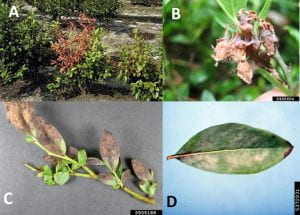

Botryosphaeria stem blight (A) will exhibit dieback symptoms. It is initially detectable as yellowing and reddening of leaves which will move down then stem as vascular tissue becomes blocked by the pathogen. Whereas, botryosphaeria canker will develop as stem lesions which will sometime become swollen resulting in the formation of a canker. If botryosphaeria stem blight or canker is observed the best method to prevent the spread is pruning the infected tissue and fruit clusters six inches below any infected stems. Then, remove pruned branches from the field.

Botrytis (B) also known as gray mold, affects both fruit and the plant. It infects the fruit from bloom. As with botryosphaeria, the best tactic to reduce the spread of this disease is by pruning out infected fruit clusters and wood, then removing clippings from the field.

Anthracnose (C) will appear as stem, bud and leaf lesions and may have orange spore masses. Infections will cause leaf browning and will move from top of the leaf to the bottom. If untreated, anthracnose will also cause fruit rot. Fungicides may be used to prevent further development of anthracnose during the green fruit

development stage.

Powdery mildew (D) will start as chlorotic discoloration spots and develop into powdery masses on leaves. The infection usually begins in the spring with young leaves and may become more severe throughout the season eventually causing defoliation. However, while unsightly, powdery mildew will not significantly damage the developing fruit crop and therefore no action is required.

Asparagus Beetle IPM

There are two beetle pests that feed on asparagus, the common or striped asparagus beetle (Crioceris asparagi) and the spotted asparagus beetle (Crioceris duodecimpunctata). Feeding on the spears results in scarring, browning, and hooked tips render the crop unmarketable. While both beetles can damage the emerging spears, the common asparagus beetle larvae and adults will also feed on the ferns, which can reduce the plant’s ability to build resources for a strong crop the following spring.

Photo by Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org

Adults: Adult beetles are about ⅓ inch in length. The adult common asparagus beetle is blue-blackish with six cream-colored square-shaped spots on its back (Fig 1). Adult spotted asparagus beetles are reddish-orange with twelve black spots on their back (Fig 2). Both the beetles overwinter as adults.

Eggs: Eggs take about a week to hatch. They are small, cylindrical, and dark-colored. The asparagus beetle lays eggs on the spear at a 90-degree angle in rows of 3 to 8 eggs (Fig 3.), while the spotted asparagus beetle oviposits eggs singularly on the fern.

Larvae: The larvae of both species are light gray with visible heads and legs. The common asparagus beetle larvae have blackheads (Fig 4.), while the spotted asparagus beetle larvae have an orange head. Larval feeding lasts for 10-14 days. Asparagus beetle larvae feed on the spear, while spotted asparagus beetles will burrow into the berry. Mature larvae crawl to the ground and burrow within the soil to pupate.

Scouting: Scouting should start at the end of April – early May or just after asparagus plants emerge and continue for the rest of the growing season. Check 10 plants in 5-10 different locations in a field, best on a warm, sunny afternoon when beetles will be most active. Treatment may be justified if 10% of spears are infested with beetles or 1-2% have eggs.

Cultural Controls & Prevention:

- During harvest, harvest all spears every day to reduce the number of stems where eggs will survive for long enough to hatch.

- Allow plants in one area to develop ferns so as to act as a trap crop. These plants can then be sprayed selectively.

- Maintain a clean environment in asparagus fields in the fall to force adults to overwinter in field edges where natural predators reside.

- Destruction of crop residues will eliminate overwintering sites for asparagus beetles.

- The most important natural enemy of the common asparagus beetle is a tiny parasitic wasp (Tetrastichus asparagi) that attacks the egg stage. These parasitoids lay their own eggs inside the beetle eggs. The immature wasps grow inside the beetle larvae, killing them when they pupate. Studies have found >50% of eggs were killed by parasitoid feeding, and half of the surviving larvae were parasitized. Providing a nearby nectar source such as umbelliferous flowers may enhance wasp populations.

Chemical Control

- Organic options on spears include Surround WP as a repellent, EC5.0, or products containing capsaicin (check for certification status).

- If possible, spot spray along edges of planting where overwintering adults colonize the field and/or band insecticide over the row to help spare natural enemies. Use selective insecticides on ferns.

- Daily harvest of asparagus makes chemical treatment difficult. 1 dh products are available and can be used immediately after picking to allow harvest the following day (see the Mid-Atlantic Commercial Vegetable Production Recommendations for current recommendations)

E. Zobel