The Eagle, the Helmsman, the Red Neck, the Exile, and September 11

José María Naharro-Calderón

In memoriam of Lauretta Clough, who was kind enough to chat with me about these …

The Summer of 2023 has been filled with a plethora of trivial or everyday Spain’s nationalism spots (Billig & Edensor). Therefore, I refer to what Billig, in line with Benedict Anderson’s subjectivities for imagining a national community, describes as an unconscious historical habitus, coined by Pierre Bourdieu, and Edensor’s studies through the display of the British sports’ original national superiority and moral manliness to rule in the colonies and beyond, and stereotypes about self-identity and otherness that emerge from internal or external clashing cultural contexts through daily and sporting styles.

Therefore, we read about the obituaries of Federico Martín Bahamontes, the first Spanish winner of the Tour de France in 1959; of Guillerno Timoner’s, six-time middle-distance world champion on bicycle after motorcycle between 1955 and 1965; the victory in the world championship of the Spanish women’s football (soccer) team on August 20 of this year, with the subsequent Rubiales soap-opera; a statement on September 5 about an amnesty for the Catalan Independence Processof Carles Puigdemont, always described by his supporters and by the former vice president of Pedro Sánchez’s government, Pablo Iglesias, as an exile; as well as the fiftieth anniversary of the Augusto Pinochet US sponsored coup in Chile on September 11, 1973, against the Popular Unity coalition which symbolically ended with the suicide of president Salvador Allende. In all these cases, as we shall observe, many onomastic signifiers point toward the signified, as Cratylus would had wished in this Socratic-Platonic dialogue with Hermogenes, who, on the contrary, defended an arbitrary and not naturally motivated sign.

This dialogue where Socrates eventually seems to favor the conventionalist argument would also point toward another ongoing linguistic-political controversy in Spain, now that three other official languages (Basque, Catalan and its derivatives and Galician) co-officially used in the Autonomous Communities of Euskadi, Catalonia, Valencia and Balearic Islands and Galicia – not to mention future claims by Andalusian, Arabic, Aragonese o fabla, Asturian-Leonese (Bable or Asturian, Montainous or Cantabrian, Extremadurian or Castuan, Leonese), Caló or Romaní, Canarian, Fala or Northern Caceres lingua, French, Panocha or Murcian, Portuguese and Rif lingua – shall employ translators and interpreters, I suspect, soon replaced by Artificial Intelligence, in the Spanish parliamentary chambers. Incidentally, I have never understood the reason for the political rejection, particularly in Catalonia, about the increase of shared public education of Spanish, as if due to its dominant position it could be learned by osmosis, and did not require the careful study of its syntax, history or literature, a curriculum mostly implemented in private schools attended by the students of the regional elites, such as Artur Mas, one of the politicians responsible for the present mess. Another similar petition on the use of Catalan, Basque and Galician in the European Union institutions seems to have opened the fear gates for a weakening and sparse European regionalization in view of the Russian threats, and an increasingly lack of cohesion within the 27 member states, where Brexit already sent a first set of panic waves, and Spanish is still not an official language, compared to English as lingua franca, French and German. The house by the roof?

Nevertheless, in the six nations European Market of the 1950s and 60s, when French cyclists such as Anquetil, Bovet, Darrigade, Geminiani, Poulidor, Rivière … won almost everything, Bahamontes emerged as the hero for many kids still on our four wheeled Orbeas. We worshiped his effigy on our soda caps, on our clay or crystal marbles, on our plastic made riders harboring the national team colors – soon to be wiped out by the commercial sponsors — through which we used to mime the Tour of France riders and races on any ad hoc street, sandy park or beach surfaces. A dynamic and modern French pilgrimage road industrially identified with the bicycle, in the path St James of Compostela’s, revitalized at the turn of the XX C., the landscapes, customs and wonders that today’s pilgrims retrace, as highlighted in the first known tourist guide: XII C Aimeric Picaud’s Codex Callistinus.

Anquetil, Rivière, Bahamontes, Tour 1959

The new French Bicycle Road was already more than a Tour, when the Toledo native, Bahamontes, was nicknamed in 1957, the year of the Treaty of Rome, by one of the organizers of the 1903 old legendary race, the journalist Jacques Goddet, as the Eagle of Toledo that would glide over the high peaks. It sent climbing the national memory of objects represented by the Carolingian emblem that presides over the Double Gate (Bisagra) of the Imperial city of the Tagus. But Bahamontes must have deeply disappointed mostly the Western-European Communitarian cycling sport fans of the time, and many of the Spanish patriotic followers of the rapacious Toledo native, by collapsing as if hit on his wings, and with his fall, digging again during that 1957 Tour, new trenches among two political and cycling Spains. In that year of his Aquiline baptism, he withdrew from the race after witnessing the schism in the Spanish team between Bahamontistas and Loroñistas, (in reference to another rider in the Spanish team, the 1957 winner of the Vuelta a España, Jesús Loroño Artega), amidst a phenomenal tantrum, covered up by an alleged health problem.

Bisagra Gate, Toledo

I don’t know if Goddet remembered that behind the emblematic appellation to the rancid Carolingian empire, the Franco regime had fluttered as a faint-hearted facilitator of the efforts of the Nazi-Fascist Axis during the Second World War in exchange for a substantial but denied Northern French-African colonial piece of the pie, which was about to become independent in Algeria (1962). The Spanish exiles of 1939 had suffered over there, as well as in the metropolis, multiple concentration camp hardships, without respect until 1945 for their right for political asylum that France had already recognized as one of the five nations signers of the 1933 Geneva Convention for Refugees. Toledo also represented a most decisive myth of heroism for the lacking representation justifying the Franco dictatorship, through the evocation of the heroes of Charles the Fifth’s Alcázar, a space for supposedly true Spain founding resistance and courage, illuminated by the divinity in favor of the coup plotters of 1936, who had held in the fortress from July 21 to September 27, 1936. Franco quickly understood its symbolic value, and therefore halted an imminent entry into Madrid in the Fall of 1936, in exchange for a propaganda picture that would make him undisputed Rebel Spain Generalissimo and eternal head of the government [and] of the state, thanks to his Super Brother’s alteration with the innocent copulative marker [and] before the partitive genitive preposition [of] on the October 1, 1936 nomination decree (Cabanellas).

Meanwhile, Spain’s National Delegate of Sports until 1956 had been none other than that former colonel Moscardó, defender of that Toledo shrine, whose commanding office is preserved with the supposed original furniture in what is the most visited museum today in Spain: the Army’s, located in that fortress-palace, which displays a first-rate museography, despite some debatable discourse that sometimes frames a few of its exhibits. For the trivial nationalism of Francoism, fundamentally exemplified by the two key male testosterone sports such as football (soccer) and cycling, nothing could happen without the omnipresent presence of that weak Delegation, in line with what many citizens have witnessed today through the preeminence of the Spanish Royal Sport Federations – note the pseudo morally social values attributed to the Crown that presides over Spain’s sport national emblems and its further symbolic consequences for the Rubiales affair – . And in order to further certify these alliances, in 1964 at the Santiago Bernabéu stadium in Madrid, a velodrome was improvised to honor both cycling champions (Bahamontes and Timoner). Meanwhile, football coliseums like the National in Santiago de Chile, may be solid arkeological sites for hiding horrid memories like the Chilean Pinochet USA supported coup d’état crimes against humanity, or cover up through monetary means, present day human rights abuses as performed in the 2022 World Football (Soccer) Championship organized by Qatar, Saudi Arabia rival football (soccer) league, or other whitewashing through cycling teams from Bahrein, United Arab Emirates, and even Israel, and its unsolvable? Palestinian conflict (https://blog.umd.edu/mondinaire/2022/11/27/while-generalissimo-franco-was-still-dead-on-november-20-2022-mientras-el-generalisimo-seguia-fiambre-el-20-de-noviembre-de-2022/).

José Varela, Francisco Franco, José Moscardó, Toledo Sept 27, 1936

In Franco’s National Catholic Holy Crusade Spain, rebaptized by cardinal Pla y Deniel, the logocentric transparency of names, surnames, emblems and symbols could be interpreted as a doubly holy sign to show that the nation of such supposedly divine ancestry was forever united by the matchmaking virtue of those very Catholic late medieval monarchs (Ferdinand of Aragon and Elisabeth of Castille) who had also built their mausoleum, never used for that purpose, in Toledo Saint John of the Kings monastery. Thus, Francoist Spain could only be the one chosen by the right hand of the Father in order to return to the lost earthly paradise of unity, – With the Empire towards God was another of its emblems- and thus establish itself and exemplify the triadic synthesis described by Levinger and Lytle about the foundations of national myths. They are based on the origins of a golden age, the subsequent decline and the glorious promise and recovery of the homeland. Does Make America Great Again ring a bell, springing from the 1845 Manifest Destiny?

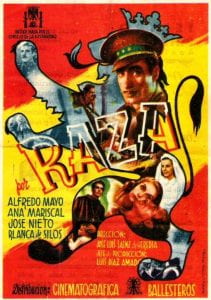

But if the diminished, underdeveloped and autarkic Spain of the frankness of its Caudillo Franco did not achieve its imperial objectives economically or politically, at least it could display them from the high peaks from which it descended like a triumphant Hispanic Trajan, certainly quite clumsily because that certain Ba(j)ha-montes (Sp. the one that descends from the mountains) used to fear the downhills. On the other hand, Timoner (Cat. helmsman) satisfied the conquering myth that Jaime de Andrade, alias Franco, spread in his 1941 film script Raza, filmed by the Phalangist Party Founder José Antonio Primo de Rivera’s brother in law, José Luis Saenz de Heredia in 1942. As a chant to Spain’s staunch traditionalism based on the former Golden Age Catholicism of empire and military valor, Timoner represented one of those Almogavars (almogávares) who had sailed the Mediterranean in command of the Aragonese fleet, reconquering the cyclist’s native Mallorca, before claiming the Mare Nostrum for Aragon which would later deliver its flows at the Castilian Hercules Columns in order to spread Plus Ultra the Hispanic Atlantic and Pacific first globalization.

Another mythical triad could be exemplified by a less heroic reading for the deterministic Frankness of the dictatorship. In the same year in which the Toledo cycling zenith seemed to confirm the imperial recovery and exemplification of the myth, Franco who had auto proclaimed himself as the Cold War Sentinel of the West, left no room for doubt about the Spanish decadence that his regime of persecution and mass graves had brought forth. Upon inaugurating on April 1, 1959, on the remains of the Cuelgamuros concentration camp, the ominous mausoleum paradoxically named Valley of the Fallen, he highlighted twenty years later that the Spanish Civil War had not ended: “The anti-Spain was defeated, but it is not dead […] attempting to revert our Victory […] Make sure that […] that you prevent the enemy, always lurking, from infiltrating your ranks.” And as Fernando Olmeda pointed out, “with this speech, the idea of winners and losers was petrified […] on the mountain of Cuelgamuros [while] Franco once again played with the deception of reconciliation [absent from] his speech, [without mention] of the fallen Spanish loyalist Republicans, nor of reaching out to the defeated.”

Spanish Republican Forced Laborers in the Cuelgamuros Concentration Camp, from where Manuel Lamana and Nicolás Sánchez Albornoz managed to escape in 1946.

https://blog.umd.edu/mondinaire/2023/04/04/los-post-seniors/

Meanwhile, part of that anti-Spain, which had managed to preserve a wick of intelligence, perseverance and care for the res publica, clear of prisons and exile, was trying to avoid a national financial Despeñaperros (a mountain range between Castille and Andalusia meaning the cliff where dogs fall over). A small group of economists, coordinated by Fabià Estapé, was attempting to invert the eschatological meaning of that mausoleum where supposedly the good overcame evil, virtue vanquished vice or light shone over darkness. Along with Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo, later second democratic Spain’s president and a signer of the 1977 stabilizing Moncloa Pacts, (Bustelo in Calvo-Sotelo), they were aware of José María Naharro Mora’s seminars divulging the modernity of a certain John Maynard Keynes, and among other recipes, the necessity of devaluating the overinflated Spanish peseta exchange rate from 10.95 to 60 pesetas to the US $, as an alternative to the renewal of rationing cards (1937-1952) and shortages that had desolated most of Spain during the long years of war, hunger and black market (1936-1952).This was the standard belt tightening recipe eternally advocated from the Flickering Light of El Pardo Palace (in reference to Franco’s official residence where his light supposedly would never be off).Therefore, Joan Sardá, a member of Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, had concluded that Franco’s dismal autarchic policies could only stem from his Supreme Reading Abilities. Sardá was another anti-Spanish exile returned from Venezuela who was able to join Estapé’s team in order to shore up and stabilize the battered 1959 Spanish economy, despite Franco’s fierce opposition.

Coincidentally, it started redressing itself symbolically on July 18, 1959, date of Bahamontes’ Aquiline triumph in Paris, or the pro Franco manipulated anniversary memento for the beginning of the Fascist coup d’état that began really in the Spanish held Rif on July 17, 1936, and which lead to the War in Spain. Two decades and a day later, Fabià Estapé was anxiously waiting at Joan Sardá’s apartment for a key announcement in the official radio news censored like an army report (El Parte). After the inexhaustible proclamation of Bahamontes’ s cycling victory on Napoleonic lands still hosting 1939 anti pure Spain enemies and exiles, the announcement finally came about the admittance of Spain to the OEEC (Organization for the European Economic Co-operation and Development – OCDE), and eventually the Monetary Fund and the tapping of USA capital loans, in order to navigate out of the morass close to inflationary bankruptcy to which Paco la culona (Francisco [Paco] Franco’s large sitting area) had subjected Spain. This was another of the Generalissimo’s motoes, used by the freemason and conservative Republican general Miguel Cabanellas Ferrer, a temporary head for the plotting generals’ junta (July-October 1936) to signify that once in command (October 1, 1936) Franco’s grip would be eternal, as implied and reflected by Alejandro Amenábar 2019 film, While the War is still On. Meanwhile, the doubtful, calculating and late future Generalissimo, had previously secured himself a golden exile, as guaranteed by a finance Almogávar, the plotting Majorca banker Juan March, just in case of a completely failed coup which eventually turned into a dismal civil and international conflict. In the opposite trenches was Guillermo Cabanellas Jr., a socialist and a participant in the 1930 Republican Jaca uprising, and finally an exile to Argentina in 1937.

In an eternal cycle of Nietzsche’s repetitions or Mark Twain’s rhymes, it was on August 20, 2023, when trivial nods to that Spanish tragic history were once again tied. A few still attempt to de/re-construct Spain while unearthing Franco’s phantoms, or what I term as “To Take out the Saint on a tour for any purpose” (Sacar a pasear el santo para un roto y un descosido) despite the fact that more than two Spanish born generations and a sizeable group of immigrants and their descendants never lived under the dictatorship, and as proven by the July 23 General Elections, when the majority of the ballots have signaled non confrontational policies. Evidently, this déjà vu of a stained past is present in other nations supposedly virgin of any blemish in their democratic origins such as France, the United Kingdom or the United States, without being affected significantly on the international arena by such past stains. On the contrary, France still rides on 1789 revolutionary mementos despite Terror or Napoleon, still commemorated, no matter what, in its Paris Pantheon. The United Kingdom washes out its colonial past through The Crown, where 1714 Treaty of Utrecht claims by Spain are diluted by Churchill’s au/ocularization as the WWII statesman, and not the Gallipoli colonialist, when facing fascist symbolic images from Franco’s times without mentioning their source. And the United States balances a controversial project about its origins such as 1619 while holding unto an undemocratic slave times Electoral College that still supersedes US presidential elections, regarded world wide, as fully democratic.

Meanwhile, Chile’s tense evocation of the 1973 Augusto Pinochet US backed coup that toppled Salvador Allende’s democratic elected coalition – please note the paradoxical Cratylic onomastic references to the Roman Emperor symbolic executioner and the Savior as victim – has been met by staunch memory battles between versions of a future of desire and one of destiny as coined by Desmond Bernal and recently quoted by David Rieff. It could be analogous to Spain so called Regime of 1978, a ruinous building bound to be demolished by the Podemos and Sumar coalitions and supporters, opposed to the consensual Transition, but defended by most of all of its alive protagonists. Therefore we are living through a hodgepodge obsession where recent history appears incapacitated and suspicious, trapped between all kinds of past and future paradoxes, and lost in the thick fog of the present, cut off by the imperatives of redemption from a past sought by youngish acting generations deprived of time but obsessed by it, while other youth ignore completely the past and do not even ascertain the present beyond the most recent trendy tweet on any subject. I have already written extensively about all this in my Entre alambradas y exilios. Sangrías de las Españas y terapias de Vichy (2017).

In contrast with this understandable morass, my generation believed it could anticipate a future of change and overcoming the dictatorships that devastated European societies such as the Greek, Portuguese, Spanish, those of the Iron Curtain and the U.S.S.R., or so many Latin American, African or Asian, among bloody conflicts like those in Indochina, against which I participated in the US as a student opponent. Thus, Pinochet’s Chilean coup represented a multiple painful regression for Spaniards like me who were waiting for the end of our endless dictatorship, who had studied the democratic tradition of Chile, the poetry of Pablo Neruda through his Spanish verses I explain a few things written in his Madrid apartment at the House of Flowers, and who as Chile’s Paris Consul who facilitated the 1,900 Spanish Republicans Exiles Winnipeg expedition to Valparaiso in 1939. Tears come to mind when contemplating in 2011 the grateful fortitude exhibited by those exiles behind the memory plaque placed in his Isla Negra residency, where he is buried after his mysterious death, a few days after the coup. I had the privilege of visiting Neruda’s Pacific Ocean residence with my baby daughter and her mother, a scholar at a José Donoso’s symposium, as another participant, José Saramago, was awaiting news about the Literature Nobel Prize Award which did not come in September of 1994. And again, I made a point of stopping at Isla Negra in January 2011 with my daughter and my current spouse, whose grand parents and uncles had been less fortunate 1939 exiles in France.

They all went entering the ship… and my poetry in their struggle had managed to find a homeland for them

Pablo Neruda

The Spaniards from the Winnipeg 1939-1997

Therefore, images keep creeping away to founding moments for my civic consciousness when one afternoon in May 1970 I went to the Film Series of the French Institute in Madrid on Marqués de la Ensenada Street to find out that the programmed film, Z by the Franco-Hellenic director Constantin Costa-Gavras, had been banned by the Franco dictatorship. A few, knowledgeable among the baffled public, commented that the film certified how the deep state could lead to the political involution of a nation symbolically as decisive for democratic ideas like Greece. I will point out that there was no such thing at the time as the internet, and that in addition, press and printing censorship were alive and kicking. As a privileged reader, I could circumvent them in the periodical section of the French Institute Library, where I could read Le Monde, and the chronicles about Spain by Ramón Chao.

Then I finally managed to view Z in the United States, at the arthouse cinema, Theater of the Living Arts on South Street in Philadelphia, along with other films like State of Siege or The Confession (L’aveu), interpreted by one of my favorite actors, Yves Montand. But I did not anticipate that Costa-Gavras’s cinema would be permanently linked to my own intellectual itinerary. Indeed, it had been framed by Jorge Semprún’s scripts, a multifaceted Spanish intellectual from exile, author of a stylized biography about Montand and his abject relationship with Simone Signoret, and a determined autobiographical reflection on his own militancy against Franco, in Alain Resnais’s La guerre est finie. That cinema displayed the multiplicity of angles, contradictions and threats for progressive politically motivated individuals and groups. I would later deal at length with some of Semprún’s cinematographic and concentration experiences, and his presence in Z explained many things about that Franco’s government ban of 1970. His multifaceted gaze thus freely crossed the contradictions that he had extracted from his own experience as an anti-fascist survivor in the Buchenwald Nazi concentration camp, and as a communist militant in the Central Committee of the Spanish party until his expulsion in 1964, along with Fernando Claudín’s, due to his perception of a country that was moving beyond the war and exile, despite Franco.

As memory kept flowing, I fell upon another tingle at the screening of Missing, and subsequent colloquium with Costa-Gavras himself, at the Annenberg Center of the University of Pennsylvania during the spring of 1982, accompanied by the poet of the Chilean exile, Raúl Barrientos, – I then shared many discussions and friendship with some of those exiles, who had followed the footsteps of the Spanish Republicans of 1939 in the Spanish departments of US universities -.With Barrientos, a renewing verse interpreter of American urban degradation, we read Pablo de Rocka and his polemic with Neruda, we chatted about the artificial paradises in modernism and Walter Benjamin’s view, or modernity in La Araucana, in which Alonso de Ercilla already gave a voice to the victims against the victimizers: Chile (…) the people it produces are so grandiose,/ so arrogant, gallant and bellicose,/ that they have never been ruled by a king/ nor subjected to foreign dominion. I had the good fortune to ask the director of Missing about the symbolism behind the image of that threatening black horse that opened the film. And he talked about the need to universalize the bestiality that underlays that story, in which he sought to convey particularly to US viewers, despite the distance from events, a process of self-knowledge and recognition of the abject interests behind the United States foreign policies, through the personal itinerary of the assassination of an American journalist and son of one of those conservative decent men. Furthermore, the interpretation that escalates with an increasing auto-contained irritation by a Hollywood acting icon from the times of Willy Wilder, Jack Lemmon, added a powerful aura of verisimilitude to the ins and outs of how the United States had moved its planetary interests in favor of dictatorial processes such as the Chilean, and as they may also hide their game when facing the unacceptable Russian aggression in the current conflict in Ukraine. Nowadays, the North American arms complex and all its adjacent industry and services benefit from this blood bath, after expanding its NATO hegemony beyond the promises of territorial restriction made to Glasnost Russia, which does not imply whitewashing Putin’s unjustifiable invasion. For those of us who have studied non-intervention in the conflict of the Spanish War of 1936-39 and the subsequent American collusion with the Franco dictatorship, a series of unanswered questions arise after this policy of intervention in what are also the consequences of area cleansing, as described in Blood Landsby Timothy Snyder.

During a recent re-viewing of the Chilean film by Costa-Gavras, analogies returned about the Franco’s Chilean Junta cloned dictatorship – along USA vice president, Nelson Rockefeller, the Philippines’s Imelda Marcos, Jordan King Hussein, and Monaco Prince Rainier, Pinochet was the only head of state present at Franco’s obituary in November of 1975. Therefore he used the same weapon of censorship when banning in Chile the Franco-Hellenic director’s powerful and universal message. Furthermore, it was Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón who sought in 1997 the extradition of the Chilean dictator from London to Spain, and activated the principle of universal justice that had been put in place thanks to the seeds of the penal doctrine of Luis Jiménez de Asúa and his discisple Manuel de Rivacoba from their Buenos Aires exile. The former was also the main proponent of the Spanish Republican Constitution of 1931, the penultimate president of the Spanish Republic in exile (1961-1970), and a professor at the Matritense School of Higher Studies at 29 Calle de la Luna in Madrid, devastated by the conflict of 1936, and directed until 1935 by Isidro Naharro López, my paternal grandfather.

Overall, even if Chilean deniers or others wish to try to erase or hide the disasters of the dictatorship, the basement spots where torture was carried out, the unclarified cases of missing persons, or the implied failures of a post-Pinochet unapproved constitution, art will prevail: in the cinema of Costa-Gavras, based on a journey of anagnorisis for the unconscious frames of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; through Patricio Guzmán’s documentaries that suture archives to capture the extensive fresco of The Battle of Chile; or thanks to Pablo Larraín’s sarcasm in The Count. All these films display how evil exists, vested interests prevent ordinary people, even within the USA democratic panacea, from obtaining justice, while our species is capable of discriminating between truths and lies thanks to our revolutionary cognitive identity in a permanent process of cultural creativity.

Meanwhile, August 20, 2023 should have represented the globally modernizing triumph of the plural Spanish women football (soccer) team over, for some Spanish nationalists, a despised English female team associated to that Gibraltar old contention stemming from the 1714 Treaty of Utrecht. The date also coincided with the long awaited first exhumation from the Francoist ossuary of Cuelgamuros, and delivery to their relatives of the remains of victims of the Franco’s conflict and repression stemming from 1936. Meanwhile it was a football (soccer) team with names with a significant Cratylic transparency which displayed Spain’s renewed national modernity: Bonmatí (Good Morning), Paredes (The Walls) or Hermoso (the Beautiful), the latter, furthermore, squeezed out from her supposed aura in the nomenclator by the arrogance of an anti-Rubiales president of Spain’s Royal Football (soccer) Federation: neither blonde, nor young, nor protocolarily adequate through his rude gestures displaying his endogenous testosterone, enhanced by some exogenous substance? He displayed what some attorneys qualify as an unjust vexation, which has now been eroded from the new Article 178 on the Spanish Penal Code which only addresses sexual aggression as a whole. Comme c’est curieux, comme c’est bizarre et quelle coincidence!/How curious, and how strange, and what a coincidence! This is how the Martins would have expressed it in the Franco-Romanian expatriate, Eugène Ionesco’s, The Bald Soprano.

But a brief perusal of the USA press these days, such as the New York Times, the most influential publication in a country where women’s soccer and other sports, – compared to American impact football are practiced massively by girls and women, in all female and coed teams – leaves no room for debate from its headlines about the negative commonplaces that unfortunately may color negatively successes from Spain. By Plural Spain (las España), I refer to the nomenclature in the Statute of Bayonne of July 7, 1808, and the pioneering 1812 Cadiz Constitution, in order to signify an incontrovertible diverse cultural geography, without impairment of the political entity of the nation called Spain, recognized for more than two centuries, and referred to for the first time in the royal title of Joseph Bonaparte (1809-1814), King of Spain, in international treaties, and of course in the Constitution of June 17, 1837, where Queen Elizabeth II was sovereign of another type of Plural Spain (las Españas as what remained also of the overseas colonies) while article 1 spoke of the territory of Spain.

The Rubiales soap-opera images became planetary, within high political tensions in Spain on all sort of touchy issues about gender and territorial nationalities, and contributed to fill in blunt covers of the summer and yellow press, to crow about trash television programs and others, and to confront even more Spain’s brothers-in-law quarrels throughout the vacation family and collective gatherings. The NYT headlined very significantly the chronicle on Spain’s women football win by Rory Smith, a journalist based in England as: For Spain, a World Cup Title Built on Talent, Not Harmony. And thus the collective effort and success of these women players in the Spanish team was immediately diminished, although, I suppose they practice, despite all problems, a team sport currently governed by FIFA, the acronym for the Fédération Internationale de Football Association [my emphasis]. This headline could be further parodied in the midst of an obsessing manosphere, as pointing out to a group of talented Quixotic actresses who would have paraded around their football spears in order to undo the wrongs to harmed needy maidens, oppressed by the abusive male giants.

In the NYT chronicle, there were implicit statements that once again replaced the apparent seny (poise) style of the other teams with a rauxa (rush) so stereotypically Catalan, as elaborated by Jaume Vicens Vives dialogically with Josep Ferrater Mora. It was sort of a note struck by chance in the style of Tomás de Iriarte’s XVIII C. tale, The Flute Donkey, glued above all by the unmatched talent of a player like the Catalan Aitana Bonmatí, the best in the tournament:

To win a World Cup, everything usually has to be perfect. The manager and the players have to exist in harmony. The squad has to be in delicate balance: between talent and tenacity, youth and experience, self-belief and self-control. A team needs momentum, and good fortune, and unity. Spain, in the year preceding this year’s Women’s World Cup, had none of those things […] It is not possible to obtain one [world cup] unless everything is just right. Unless, as Spain proved, you have the talent — bright and clear and irresistible — to make sure nothing can go wrong.

Therefore, a spontaneous, natural and arbitrary alignment of stars justified the astonishing Spanish improvisation win – I assume a Catalan fluke included, as that region’s nationalist rushed to point out the noted presence of local players – compared to the expected orderly standardized and stereotypical cultural and stylistic displays from the moral rectitude in the English sport’s birthplace. And to chance, we must add the coarseness, the rudeness, the machismo, the truculence, the arrogance coming from the Rubiales male lead surroundings of the Spanish women’s locker, which has confronted the courageous and resisting players and the Federation, certainly as a clear sign of un-Francoist changing times. It filled up the International headlines of the NYT, not its Sports section, on September 5, more than two weeks later, with the dismissal of the women’s soccer coach and finally, the resignation of Rubiales on Sept 10 and so on and so forth, as a sort of Spain’s Me Too movement. Again and again, the chronicle referred to the gap between the tradition of machismo (a global etymologically Spanish word) and a rights vanguard modernity: a spotlight on a divide between traditions of machismo and more recent progressivism that placed Spain in the European Vanguard of feminism and equality. A reference to the avant-garde with a subtle paradox for the use of the concept of modern tradition that the exile to the United States in 1936, Juan Ramón Jiménez, had already discussed through his concept of modernism, of course, distant from these cacophonous wording rallies.

I estimate that to the Spanish authorities’ regret, the image of Spain has never enjoyed a more steady stream of headlines in the NYT, if we except the time of the Cuban-Spanish-American War of 1898, and the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War. I have never understood that popular saying, – maybe a reflection of the histrionic exhibitionist digital vanity of our day -, that speaking ill of one is preferable to silence. Although the order of the factors does not alter the product mathematically, syntactic hierarchies may certainly hide or reveal cultural prejudices and/or favoritisms. Clearly, the symbolic and overwhelmingly sexist gestures of this sporting red neck and his accomplices has prolonged Spain’s negative image. Meanwhile, frequent achievements, not only in women sports, but through so many female Spanish artists, humanists, scientists, NGO volunteers, for example, the one recently killed in the war in Ukraine, etc., and their corresponding male examples, do not ever reach the headlines of any global paper such as the NYT.

These unfortunate shortcomings may be added to the supposedly democratic deficits which some also accuse the negated collective nation of Spain, while they auto proclaim themselves as exiles and they boast about Catalonia’s Contributions to the Social and Political Progress of Europe Throughout its History, in an exhibition inaugurated in the European Parliament by Carles Puigdemont and Toni Comín (etymologies, for the one who climbs the mountain, and the cumin seed, — the latter, not highly respected in the Spanish popular saying, he is hardly worth a cumin seed –). This exhibition highlights the Consolat de Mar, a pioneering institution in maritime and commercial legislation; the creation of the Remença Agrarian Union; the Court of Contrafaccions, considered a precursor of modern constitutional courts; and finally and most paradoxically, popularly known as the Canadian strike in 1919, performed also by a non-Catalan working population, affiliated to the Anarchist CNT, and who managed to obtain Spain 8hrs working days, while facing the Catalan management of the North-American founded Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited.

The stridency of the debate about local nationalities and the separatist and separating partisan efforts have spread across the Spanish political aisle of the Herderian anti or pro Spanish nationalist parties, as represented mostly by Basque, Catalan and Galician nationalist groups vs the ultra right Spanish Vox, a sector in the Popular Party (PP), as well as a few militants in the Socialist PSOE. Meanwhile, the semantic rectitude of auto qualifying or calling an exile, Catalan Nationalist Carles Puigdemont (etymologically, also the one that heads to the mountain – takes to the woods), has long been defended by the pro referendum Spanish Podemos affiliated federalists such as Pablo Iglesias, who initiated a Popular Front political strategy in 2014 which has fractured Spanish politics with alliances and discourses that evoke the Second Spanish Republic clashes, certainly, without the risk of a Civil War, as guaranteed by the European Union framework. Puigdemont may then be viewed, as reincarnating a saint from the Mountain of Beatitudes, a Christ figure redeemer’s preaching a Sermon on the Mount to his lost Catalan people, or as an apocalyptic anti Christ, the devil that tempts the Spanish socialist Messiah, Pedro Sánchez, on Mount Quruntul, with all his meager but precious material riches (7 parliamentarians that may tip off in his favor the future Spanish government), while luring the prime minister into spiritual servitude by conceding an amnesty to all Catalan 2014-17 prosecuted separatists. Meanwhile, thoughtful debates confront jurists touched by various flags and ideologies in order to ruffle the loop of the post-electoral justifications for an amnesty for those accused of embezzlement for the unilateral 2014 and 2017 referenda on independence. But they are certainly politically responsible for the unilaterality of certain decisions taken in Catalonia, which by the way can always provide fuel to themselves and their foes, by confronting, among others, Catalans who are also Spanish velis/nolis in the said territory. While other voices hold angry disputes around the possibilities of further secession referenda and their various articulations. Curiously, Javier Melero, a respected penal defense attorney for some of the Catalan Referendum 2017 politicians, has quoted Jiménez de Asúa’s cautious but romantic 1931 constitutional point of view about amnesties.

Therefore, exile is a term whose terminological abuse, in this case, hides its relatively recent incorporation into the Spanish lexicon, since its French usage (from lat. Exilium) was only picked up through the presence of Spanish emigrees or refugees in Latin America from 1936-39 on., where éxil and éxilé, were much more frequent. The defenders of the term for independence in Catalonia are right if we attribute to the term the second meaning in the dictionary of the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language as expatriation, generally for political reasons, that is, motu proprio displacements. But we would be inaccurate if we were to consider expatriate as a synonym for exile, and we ignore the historical-political contexts that should color such ostracism, to which we must add ideological persecution for undemocratic reasons, due to the oppressive intolerance of a regime. Persecution, lack of fundamental rights that surround modern exiles, which only became widespread with the surge of liberal systems and constitutions which gradually guaranteed popular participation processes in the collective decisions of nations. Exiles became modern in nature from the 18th century on (in particular with the Declaration of the Rights of Man, as the French version of August 4, 1790 reads) or with article 120 of the French Montagnarde Constitution of 1793, never approved, which states that France welcomes those fleeing tyranny and will persecute those who promote it, as the origin for what would later become the 20th century Geneva Convention on Refugees.

Some readers will point out that Mr. Puigdemont precisely defended the said popular participation with respect to what Charles Tilly describes as state-seeking nationalism. But for the United Nations, Spain, despite having been dubiously admitted into that international body in 1955 during the Franco dictatorship, thanks to the Western-USA interests of the Cold War, today is a full-fledged nation-state, and therefore exempt from possessing colonies with the right to self-determination; except for its former territory in Western Sahara, abandoned unilaterally by Mr. Sánchez to Morocco’s occupying logic in 2022 in line with the Israel-USA interests. This executive Spanish decision therefore assumes an Almanzor Syndrome (Mangas in Aragón) or a blackmail foreign policy as displayed by Morocco through its erratic emigration safekeeping-open the gates tactics, particularly in Ceuta, Melilla and across the Canary Islands, while Brussels still banks on burying its head in the sand about the Mediterranean immigration pandemia.

Meanwhile, Spain presently respects the fundamental rights of its citizens, and particularly of women, through free expression at the polls, or thanks to other progressive laws, all constitutionally protected by a 1978 Magna Carta, which may of course be improved, and also messed up (as recently shown by legislation on Sexual Rights that had to be amended, popularly known as the Yes is Yes Law which its Podemos legislators and Socialist acolytes approved, despite its flaws which shortened prison sentences for prior condemned sexual offenders. Of course, this may happen to any legal text subverted by any supposedly Sapiens mind, as Hadrian expressed it in his fictional memoirs by Margarite Yourcenar when he points out that laws change less quickly than customs; that they are dangerous when they come behind the curve of social morality, and even more so when they are ahead of their times (elles changent moins que les mœurs; dangereuses quand elles retardent sur celles-ci, les le sont davantage quand elles se mêlent de les précéder).

Let’s preserve ourselves against the manipulative abuse of naturalizable semantics surrounding a Herderian style earth and blood Catalan nationalism, represented by its September 11 Diadas, the date of their supposedly 1714 freedom loss, the Basque Aberri Eguna or Basque Homeland, Misty Galician Celtic origins, or Spanish Trajan and Hadrian Roman Empire sources, and even prehistoric ones at Atapuerca. In Catalonia, the 1714 defeat and exile legitimization tends to overshadow its anti-Bourbon pro Austrian partisans’ exile within an international absolutist monarchical conflict and its economic hard liquor ties to the English trade. Let’s rather focus on the exiles suffered by XIX C. liberals (a Spanish political term from the 1812 Cádiz Constitutional Congress), still present in spirit in Florida St. Agustin Spanish Constitutional monolith), and later on the foreign plights of defenders of the First or the Second Spanish Republics, who had to flee Spain to avoid, as we know, in the latter case, Franco’s mass graves. Finally, a 2022 Law of Democratic Memory may facilitate their overdue banishment to the trash heap of history.

Plaza de la Constitución, San Agustín Florida, USA

Utopian illusory types like me hope for the erasure of these various semantic-territorial determinisms, or the pre-eminence of identity languages for new national states, compared to the obvious advantages for the Iberian polyglots, including Portugal, like the Asturian-Bable space from which I am writing, – let’s welcome the richness and cultural respect for the diversities of logos from any and everywhere, and the representation and/or political reform for the stability and accommodation for non Spanish minorities, (Basque, Catalan, Galician) already quite widely guaranteed by the constitutionalstate of the autonomies, ratified today through the usage of plural languages in the parliamentary Spanish debates. But let’s try to avoid all underground wars in order to deform national linguistic imaginaries, accommodate history and thus justify patriotic ruptures, particularly in Catalonia and Euskadi. Those territories may have been previously separated entities, but in non democratic moments distant from the unitary plurality of the present. And let’s not forget that the Spanish Magna Carta and laws ratified by the Constitutional Court do not curtail the rights to defend a hypothetical self-determination, certainly based on complex mechanisms that guarantee the constitutional stability of nations in the European Union, and of course, regulated by and for the entire Spanish electorate, not just a few privileged ones chosen by blood and earthy distinctions. War associated by François François Mitterrand to separating nationalisms has not ceased to show its marks in so many new nations (Tortella & Quiroga Valle) through the dangers of their secularized former or newer identity fleeces, and as rooted somehow in the Ukraine-Russian conflict. Therefore, let’s utter a ¿cynical? mantra about recyclables, anytime new nationalism nightmares creep up, or what the American revolutionaries pragmatically stated in the preamble of the 1776 Philadelphia Declaration of Independence: Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

Nor should we think about catastrophic figures and exceptional cases, for example around the supposedly longevity limits for certain political moments in Spain’s history, as referred by a disheartened novelist such as Pío Baroja, when he attributed a string of bad luck to the liberal past until the Second Republic. Recently, Felipe González referred himself to the XIX C. Restoration, Franco’s Dictatorship or the post-1978 constitutional period, as if they were the result of some repetitive Hispanic fluke. Let’s blur the vicious circle cycle of essentialist confrontations between various territorial Spains that the present egalitarian and proportionally distributive civic constitutionalism, with noted fiscal exceptions for the Basque Country and Navarre, attempts to regulate, certainly, through a maze of yearly budgetary regional disputes: What about me? Could we regenerate forms of the habitus of the past, when a president like Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo frequently received in La Moncloa Palace, whom he understood would be his successor, Felipe González, not as a political enemy but as an adversary who would have to continue taking care of the res publica (Calvo-Sotelo, López de Celis). It may teach us to stay clear of Olympian heroic discourses and away from any of the various trivial and essentialist nationalisms, including the Spanish one, in the face of the consistent and harmonious work and planning of so many citizens who, as mentioned earlier, even in moments of dictatorship and exile, have contributed to Plural Spain’s improvements in a country named Spain, where as claimed by a 1936 visitor to one of the Anarchist columns on the Aragon front, French thinker Simone Weil, human creativity seemed to focus mostly on the camp of negativity rather than goodness.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ademollo, Francesco. The Cratylus of Plato: a Commentary. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Amenábar, Alejandro. Mientras dure la guerra. 2019. Divisa Home Video, 2020.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised ed. London: Verso, 2006.

Andrade, Jaime de. Raza (1941). Barcelona, Planeta, 1997.

Aragón, Manuel & Fundación Colegio Libre de Eméritos Universitarios. España: Democracia menguante. Madrid, Fundación Colegio Libre de Eméritos Universitarios, 2022.

Baroja, Pío. La guerra civil en la frontera. Madrid, Caro Raggio, 2005.

Billig, Michael. Banal Nationalism. London, Sage, 1995.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Raisons pratiques: sur la théorie de l’action. Paris, Seuil, 1996.

Cabanellas, Guillermo. La guerra de los mil días: Nacimiento, vida y muerte de la II República española. 2. Buenos Aires, Editorial Heliasta, 1975.

Calvo-Sotelo Ibánez-Martín Pedro, editor. Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo: Un retrato intelectual. Madrid, Marcial Pons, 2011.

Costa-Gavras, Constantin. État de siège. Reganne Films, 1972.

—–. L’aveu. D’après le récit de Lise et Artur London. Screenplay by Jorge Semprún. Films Corona U.A., 1970.

—–. Missing. 1982. Criterion Collection, 2008.

—–. Z. 1969. Screenplay by Jorge Semrún. ARTE France développement, 2021.

Edensor, Tim. National identity, popular culture and everyday life. Oxford, Berg, 2002.

Ferrater Mora, José. “Tres mundos: Cataluña, España, Europa”. Obras selectas. Vol. 1.

Madrid, Revista de Occidente, 1967. 199-307.

Genette, Gérard. Mimologiques: Voyage en Cratylie. París, Seuil, 1976.

Guzmán Patricio. 1975-79. La batalla de Chile: la lucha de un pueblo sin armas. Icarus Films, 2015.

Larraín, Pablo. El conde. Netflix, 2023.

Levinger, Matthew & Lytle Paula Franklin. “Myth and Mobilization: The Triadic Structure of Nationalist Rhetoric,” Nations and Nationalism, 7(2), pp. 175–194, 2001.

López de Celis, María Ángeles. Los presidentes en zapatillas: la vida política y privada de los inquilinos de la Moncloa. Madrid, Espasa, 2010.

Melero, Javier. “La amnistía triste”. https://www.lavanguardia.com/opinion/20230919/9235595/amnistia-triste.html

Naharro-Calderón, José María. Entre alambradas y exilios: sangrías de las españas y terapias de Vichy. Madrid, Biblioteca Nueva, 2017.

Olmeda, Fernando. El valle de los caídos. Una memoria de España. Barcelona, Península, 2009.

Resnais, Alain. La guerre est finie. Screenplay by Jorge Semprún. Les films des Deux Mondes, 1966.

Rieff, David. “La persistencia del 11 de septiembre”.

https://elpais.com/opinion/2023-09-15/la-persistencia-del-11-de-septiembre.html

Saenz de Heredia, Jose Luis. Raza. 1942. Filmoteca Española, 1993.

Semprún, Jorge. Montand, la vie continue. Paris, Denoël, 1983.

Snyder, Timothy. Blood Lands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. New York, Basic Books, 2010.

Tilly, Charles. European Revolutions, 1492-1992. Oxford, Blackwell, 1993.

—–. The Formation of National States in Western Europe. Princeton, Princeton U. P., 1975.

Tortella Casares, Gabriel, & Quiroga Valle María, Gloria. La semilla de la discordia: El nacionalismo en el siglo XXI. Madrid, Marcial Pons Historia, 2021.

Yourcenar, Marguertite. Mémoires d’Hadrien. Paris, Gallimard, 1971.

Vicens Vives, Jaume. Noticia de Catalunya. Barcelona: Ediciones Destino, 1954.

Weil, Simone. L’enracinement: prélude à une déclaration des devoirs envers l’être humain. Paris, Gallimard, 1949.